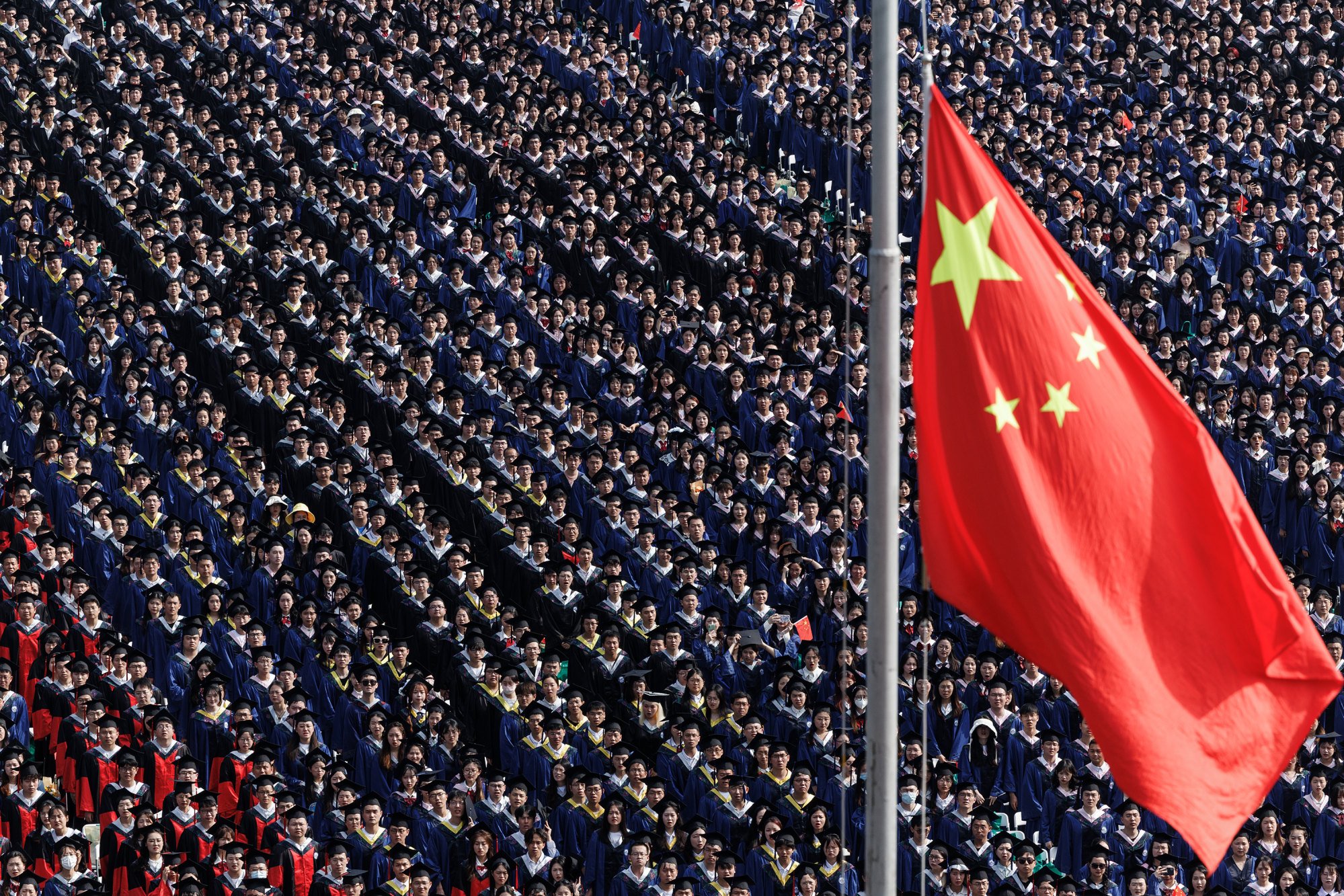

China’s army of young graduates should be considered assets, not liabilities, for the country’s development

- In 1999, China had just 850,000 graduates, whereas this summer 11.8 million young Chinese will graduate from colleges and universities

- If China can loosen its grip and unleash the creativity and entrepreneurship of tens of millions of educated youth, then the future will be boundless

One of the most eye-catching accessories a young person could have in China was a pen in the upper left pocket of a Mao suit, as it signalled to all that they had received a formal education. Those with college degrees could even be forgiven for carrying two pens in their shirt’s breast pocket.

But those days are long gone. Such privilege, and the education the pen represented, quickly faded over the past quarter of a century. Nowadays, a diploma - even when issued by one of China’s top schools - is no longer a guarantee of employment given the “army” of young people with higher education across the country.

In 1999, when China decided to expand enrolment of college students, the country had just 850,000 graduates. This summer, China expects to see 11.8 million young people graduate from colleges and universities. However, finding jobs for educated youth has become a headache for authorities, schools and households. That has brought a sense of disillusionment to many young graduates.

Amid job market woes, China to add another 11.8 million graduates to workforce

The “democratisation” of higher education represents huge progress in China. For thousands of years it was seen as a privilege reserved for elites. Then for the first time in China’s long history, most of its young people were able to be admitted to colleges and universities.

In 2022, the number of new graduates already exceeded the number of births, and the trend is set to continue in coming years. This theoretically means every Chinese child born after 2022 will receive higher education if the country’s colleges maintain their current scale. For a nation with low fertility rates and an ageing population, a sizeable cohort of educated young people should be seen as an asset, not a liability, for the country’s development.

Some Chinese economists now argue that the country has gone too far in enrolling young people into colleges, and that this trend goes against the nation’s economic planning. Under this planned-economy mindset, the government has started to draw an artificial line at the ninth grade, where half of the students would continue to high school and take college entrance exams, while the remainder enrol in vocational training schools.

The policy is poorly-designed and extremely short-sighted as it denies access to higher education for half of the country’s youth in a bid to correct a domestic shortage of manual labour. As the Chinese saying goes, this is like cutting off your toes so your feet can fit inside your shoes.

One aspect of Beijing’s education policy, just like its family planning policy, is its excessively utilitarian view that people are just inputs into the social and economic machine. By this thinking, if China values “hard tech” and “advanced manufacturing”, the country will not need so many graduates.

But if China can loosen its grip and unleash the creativity and entrepreneurship of tens of millions of educated youth, then the future will be boundless. Nvidia, the American graphic processing unit giant and a key player in the era of generative artificial intelligence, initially thrived because its products were widely adopted by video gamers – a form of entertainment that Beijing has put under heavy scrutiny.

Top Chinese university becomes first to remove English requirements

While Chinese authorities have pledged to help graduates find jobs, many policies are actually destroying jobs for the country’s youth. One typical example was Beijing’s abrupt decision to ban ex-curriculum private tutoring in the name of reducing the burden for primary and middle school students. In a single stroke, the potential job opportunities for millions of Chinese youth were eliminated. The de facto ban on live talk show performances, after one bad spontaneous joke from a performer, is another example of “smashing the rice bowls” of the country’s youth.

As a result, China’s young people are forced to compete for a tiny number of governmental or state sector jobs. It is truly a pity to see how the country’s most valuable human capital is being wasted.