Changing of the guards

It’s a once-in-a-decade exercise. Behind closed doors, deals are struck and broken, careers are bought and sold, battles are won and lost. When the white smoke finally rises from the conclave chimney, new kings are crowned and another layer of intervening leadership is added to one of the most opaque political systems in the world.

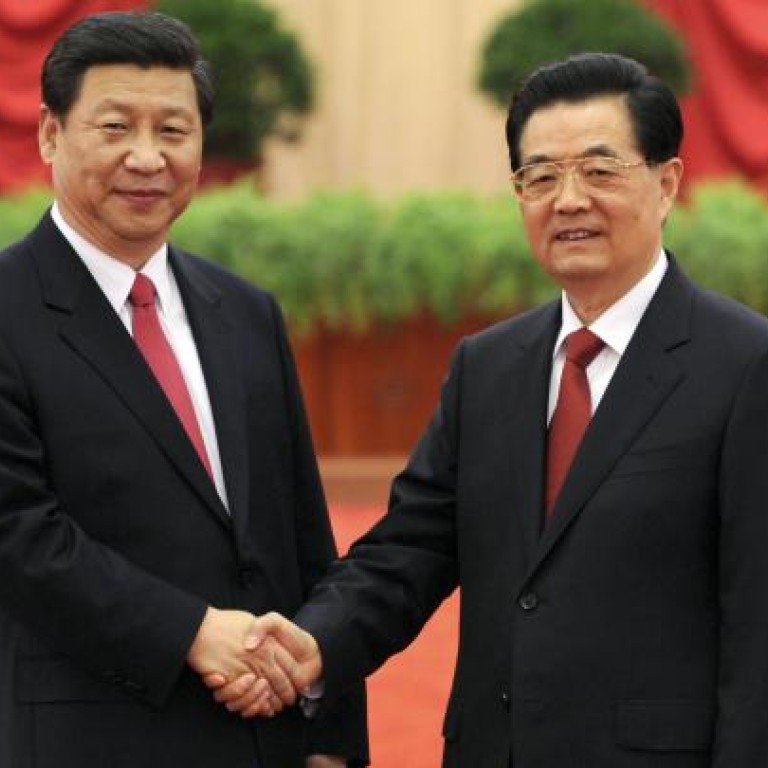

The 18th National Congress of the Communist Party of China (第十八次黨代表大會) opened on 8 November and concluded less than a week later. Just as pundits had predicted, Xi Jinping (習近平), the rotund Beijing native and scion of a well-known party elder, emerged as the new paramount leader. To the rest of us on the other side of the door, the Party's National Congress is little more than an auditorium full of men (and an occasional woman) in black suits and red ties applauding on cue. Though that’s not far from the truth, exactly what the National Congress does and how it is different from similarly-named bodies like the National People’s Congress or NPC (人民代表大會) continue to elude us. Before we talk about the leadership change, we begin with a crash course on Chinese politics.

Chinese Politics 101

The National Congress is made up of 2,270 delegates from the Communist Party of China or CPC. With the CPC’s membership topping 83 million, the National Congress is a very exclusive club. Unlike the NPC, the National Congress is not a legislative body or even part of the government. It is simply the CPC’s own caucus that meets every five years to select and promote new party leaders. Think of it as the Republican National Convention in the U.S. that nominates a presidential candidate in an election year.

After the scourge of the Cultural Revolution, the CPC needed to prevent another personality cult by reshuffling their leadership every few years. In the 1980s, a pyramid structure was formally put in place. Twice a decade, the National Congress is called to elect the 205-member Central Committee (中央委員會), which in turn elects the powerful 25-member Politburo (中央政治局). The Politburo is the CPC’s nerve centre where important policy decisions are made. A seat in the Politburo guarantees fortune and fame, often in the form of high-ranking regional positions. The Politburo then elects the seven-member Politburo Standing Committee or PSC ( 政治局常委會), the most exclusive club in Chinese politics. Each PSC member is responsible for a major national issue, from the economy to corruption and propaganda. The PSC is chaired by the General Secretary, the highest office in the land.

That’s how things are supposed to work on paper. What happens in practice, however, is a different matter. First of all, the word “election” is used loosely in Chinese politics. The line-up of the Politburo and the PSC is determined by endless horse-trading and power struggles behind the scenes. The National Congress and the Central Committee are mere formalities to rubber-stamp whoever party elders pre-ordain. Second, the concept of retirement is alien to strongmen who have stepped down from their posts. As long as they still have a pulse, retired leaders continue to exert their influence by stuffing the Politburo with their own allies. Since Jiang Zemin (江澤民) stepped down in 2002, he has remained an éminence grise in key party decisions. Jiang was widely seen as the man responsible for Xi Jinping’s meteoric rise through the ranks and reportedly blocked two pro-reform candidates, Guangdong party chief Wang Yang (汪洋) and Head of the Organization Department Li Yuanchao (李源潮), from entering the Politburo last week. Because retired leaders refuse to give up control, each generational leadership change ends up throwing more people into a kitchen that already has too many cooks. And you know what they say about spoiled broth.

One Country, Two Factions

China is an autocracy. But what it lacks in multi-party dissent, it makes up for in factional politics. Exactly how many factions there are and who plays on which team is unclear. What we do know is that there are two main coalitions: the Populist Coalition comprising the Youth League Faction (共青團派, or 團派) and the Qinghua Clique (清華幫), against the Elitist Coalition made up of the Shanghai Clique (上海幫) and the Princelings (太子黨). The two coalitions have two different visions for the country. Led by outgoing President Hu Jintao (胡錦濤) and Premier Wen Jiabao (溫家寶), the Populists favour social harmony and a welfare state. By contrast, the Elitists, led by Jiang Zemin and his protégé Xi Jinping, are more interested in economic growth.

Diagram created by Jason Y. Ng.

Who is Xi?

Party infighting notwithstanding, the National Congress must go on. At the eleventh hour, a deal was struck between the coalitions and Xi Jinping was anointed the fifth-generation party chief. Following in the footsteps of his predecessors – Mao, Deng, Jiang and Hu – Xi has assumed other powerful positions including Chairman of the Central Military Commission (中央軍委主席) and will become President when the NPC convenes in March 2013. Xi’s rise to political stardom is a far cry from his humble beginnings. After his father, a CPC founding member, was purged during the Cultural Revolution, Xi was exiled to remote Shaanxi Province for seven years, some of which were spent in a cave. His childhood hardship, combined with overseas exposures including a short stint in Iowa, set him up to be a different kind of leader: a more down-to-earth and progressive kind. But don’t get your hopes up that Xi will be China’s Mikhail Gorbachev. Jiang and other anti-reform elders are expected to monitor his every move, while political opponents like Hu and his protégé Premier-in-waiting Li Keqiang (李克強) will also keep close tabs on him. Li lost the bid for the top job to Xi and will begrudgingly play second fiddle to his princeling rival. Until Xi consolidates his power and builds his own political base (which may take years), he is likely to remain a status quo chairman.

Xi’s Mandate

In his first public speech as General Secretary last week, Xi Jinping described corruption as a “severe challenge” and a “pressing problem.” The unusually dire rhetoric suggests the CPC’s determination to tackle a longstanding party ailment. But that’s easier said than done. Corruption is a toxin that has poisoned every level of government in China, widening the income gap and fueling social unrest in the process. Bribe-taking is no longer only about money and greed; it is a show of solidarity and a badge of honor. In an environment where everyone takes a little kickback here and offers a little hush money there, being a goody two-shoes makes you a bad team player. Bad team players don’t do very well in Chinese politics.

Under this climate of coercive corruption, it is unclear whether Xi’s anti-graft rhetoric is anything but lip service. After all, some of Xi's family members have reportedly amassed astronomical wealth in equity investments through an intricate structure of holding companies. He who lives in a glass house should think twice before throwing stones, especially when all his neighbours live in one too. It is possible that all that talk to dahei (打黑; literally, fight black) is simply a battle cry to intimidate his enemies. Anti-corruption has always been a convenient excuse to purge political opponents, just as Bo Xilai did when he took the helm as Chongqing’s party chief in 2007. Over the course of three years, Bo put away an estimated 5,700 government officials, judges and businessmen who stood in his way to power. If Xi is looking for a way to firm up his foothold in Beijing, he just may borrow a page from Bo’s playbook.

The China that Xi Jinping inherited from Hu Jiatao is very different from the one Hu inherited from Jiang Zemin a decade ago. Sustained economic growth won’t go on forever and the system is slowly spinning out of control. If Communist China is a runaway train, then corruption is the coal that’s speeding up the engine. One false move – whether it is an economic downtown or another political scandal – and the train will fall off the cliff. Sensing the inevitable, government officials have been sending their children abroad and transferring their ill-gotten wealth offshore, with the side effect of driving up property prices all around the world. If the runaway train is not stopped in time, there may not be another changing of the guards in ten years. Xi has his work cut out for him.