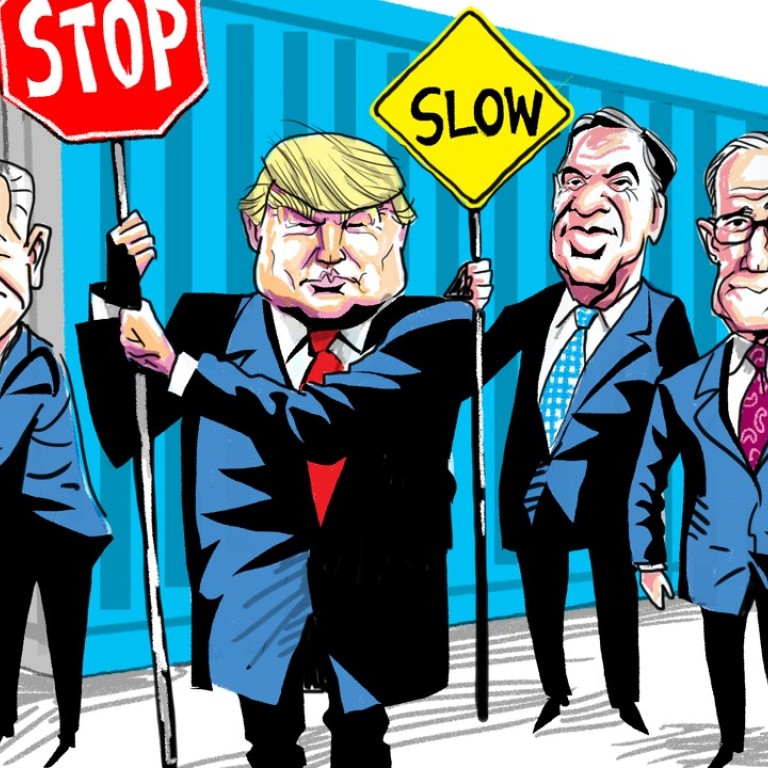

Trump’s ‘coordinated chaos’ may be part of a grand strategy, one that doesn’t bode well for China

Scott Kennedy says US President Donald Trump’s administration seems to be following a ‘mixed message’ strategy and gearing up for a long-haul battle with China that is not restricted to trade

But then along came Trump’s tweet, applauding Xi for his “kind words on tariffs and automobile barriers” and “his enlightenment on intellectual property and technology transfers”. Many breathed a sigh of relief, believing that the two sides are moving closer and that a trade war is highly unlikely.

But my reading is the opposite: it is increasingly clear that the US and China are heading for an extended commercial slugfest. The key to seeing through the current confusion is to understand that the Trump administration is following a distinctive communications strategy.

Traditionally, credibility is key to winning a trade war. Your opponent must believe that you are willing to punish them, even at great cost to yourself, for you to have any chance of getting them to meet your demands. And credibility comes from having a reputation of carrying out your threats and by maintaining a consistent message from everyone on your side.

The administration may have concluded that it would require the imposition of massive unilateral measures before Xi would make major concessions in turning China into a market economy

Given the broader signs of disorganisation and inconsistency, one shouldn’t exaggerate that there is a clear master plan on China and trade. But the administration is, at a minimum, following what one close observer calls “coordinated chaos”, with a common sense of the overall policy direction and an acceptance of the benefits of different officials playing different roles.

If the goal is to have China surrender before the US fires a shot, this approach is misguided and has failed spectacularly. But there are two other explanations, both of which are ominous for China and the bilateral relationship.

The administration may have concluded that it would require the imposition of massive unilateral measures before Xi would make major concessions in turning China into a market economy. This suggests a lengthy conflict and financial markets may need time to adjust to this new normal without tanking. Hence, it makes sense to have threats to China writ large but also to soothe markets and butter up Xi.

If so, the moves towards protectionism aren’t meant to be temporary and removed should China liberalise, but rather are intended to be permanent, aimed to weaken China and to disengage the economies of the two countries.

The administration may be carrying out a complex ruse to make China believe that reconciliation is possible to dissuade it from taking drastic action in the near term against American commercial and strategic interests.

The only question is how long the conflict will last. The administration may have an eventual exit strategy once it believes commercial ties have become “fair and reciprocal”. But China might wreck these well-laid plans and believe that being enemies is our new shared destiny. Then the two countries would be locked in a longer and broader conflict than originally planned.

In short, it is in the Trump administration’s self-interest to clarify its messaging so that there is absolutely no misunderstanding about the potential dangers – and opportunities – that lie ahead.

Scott Kennedy is director of the Project on Chinese Business and Political Economy at the Centre for Strategic & International Studies. His most recent book is “Global Governance and China: The Dragon’s Learning Curve”