How blockchain can save Chinese bike-sharing firms from the pitfalls of selfishness

- Ethan Lou says China’s bike-sharing sector has been hard hit by low profit margins and a high rate of bicycle theft. Companies would benefit from using a blockchain platform that frees them from the responsibility of mediating in cases of dispute

In December, Ofo faced cash-flow problems so severe that a Beijing court placed spending restrictions on its founder’s lifestyle. The company even considered bankruptcy, capping a painful three years for China’s billion-dollar sharing start-ups. Ofo is backed by Alibaba, the parent company of the Post.

But Uber and Airbnb offer high-value assets that people normally rent at a premium. There is enough room in the prices people usually pay to ensure the company gets a big enough cut to cover that cost of selfishness.

The Chinese companies’ low-value items fetch paltry sums. Each bike makes about 15 US cents per two-hour ride. Why these companies failed is obvious in retrospect.

A scaled-up sharing economy saves money. It gives people easy access to items they do not use often, without having to buy them and have them pile up in garages. A 2018 survey shows average British homes have over £2,300 (US$3,000) worth of unused items. More sharing is also better for the environment.

But the high cost of selfishness is an unfortunate function of who we are. It makes it almost impossible for companies to facilitate the large-scale sharing of lower-value items.

That is ultimately because of centralisation. Companies devote resources to fighting abuse and mediating disputes because controlling the platform gives them the power to right wrongs. However, this power also entails responsibilities that cannot be relinquished.

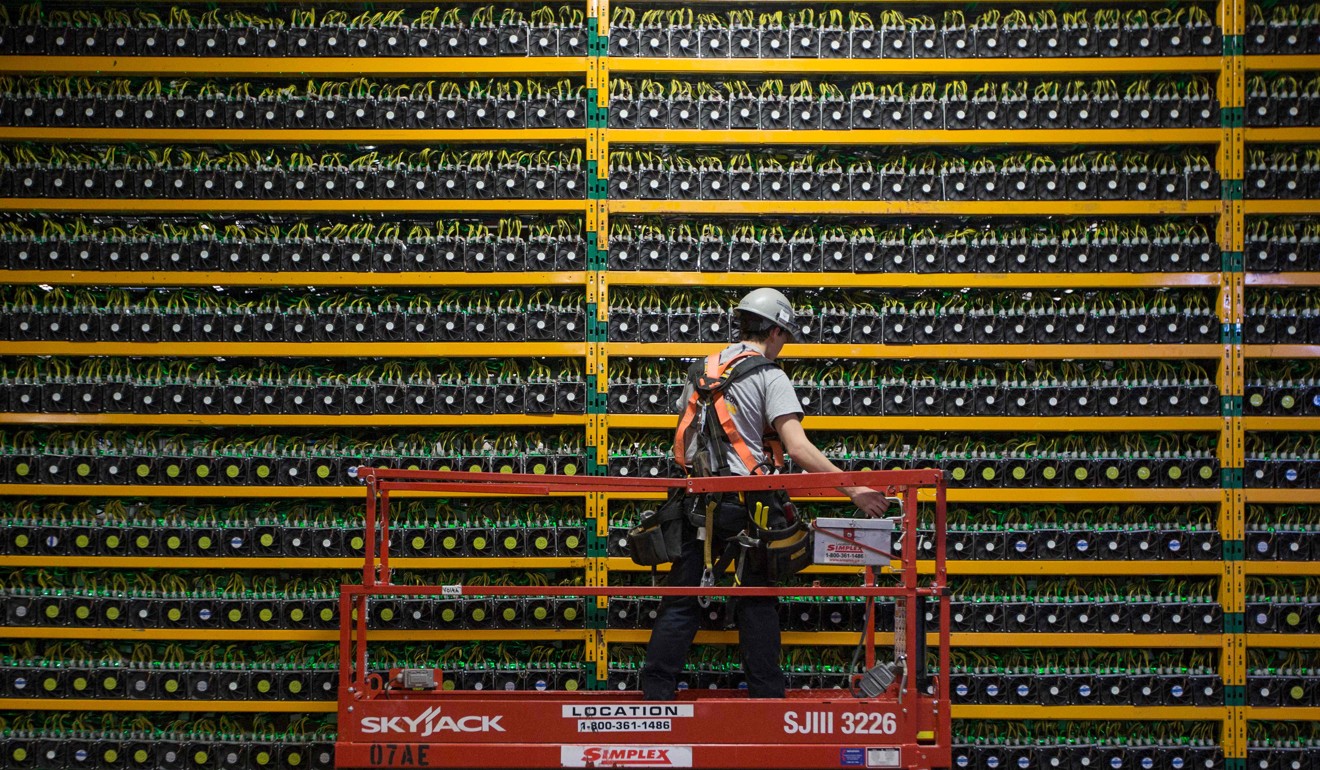

But what if companies need not have that power? Enter blockchain, a record-keeping system without a central authority that allows bitcoin users to directly pay each other. Coders are already extending the use of blockchain to other types of peer-to-peer interaction.

A sharing platform built on blockchain connects lenders and renters directly – different from the interaction on Airbnb, which acts as a middleman for payment and has centralised servers in the company’s offices.

A blockchain platform has no centralised servers, needs no offices and runs on preset rules without ongoing management by its creator, who no longer has control.

Not only is the creator not able to intervene in the system, it cannot be compelled to do so by any means. The sharing platform stops being a mediation hub – and that would be made abundantly clear to users before they sign up.

This means companies no longer bear the cost of selfishness and can profitably facilitate the large-scale sharing of lower-value items, such as a bicycle or a hammer.

That shifts the cost of selfishness to the victims and is far from perfect. But it is no different from how there is no one to sue or complain to – except the police – if a neighbour borrows your car and runs away.

A blockchain platform will not be more unsafe. A traditional sharing platform only compensates the victim and does not have the power to inflict significant real-world punishment on an abusive user. There is no deterrent effect. The frequency of abuse will be the same.

A blockchain platform will still have the same verification, testimonials, ratings, screenings and deposits to prevent theft. It’s just that, when an issue comes up, users will have to resolve it themselves.

That does require a shift in people’s thinking. But it would be no bigger than the shift a decade ago that made people think opening their homes to a stranger via Airbnb was acceptable.

Ethan Lou is a senior partner at the Canadian cryptocurrency firm Ocuis. He was formerly a journalist with Reuters