How the coronavirus and US-China conflict are driving Beijing’s domestic focus in the new five-year plan

- China has moved away from its ‘reform and opening up’ approach and turned to domestic development with a new emphasis on self-reliance, technology and quality growth

- The shifting geopolitical landscape and uncertainty over domestic and international consumer demand in a post-pandemic world suggest a bumpy road ahead

As a centrally planned economy, China has followed a carefully calibrated long-term strategy and made significant breakthroughs in the global system. Therefore, its new five-year plan has attracted much attention.

While China might need to improve the way it implements its strategies, Beijing still favours national planning to manage the world’s second-largest economy. As such, one should pay careful attention to its five-year plans to gauge policy priorities from Chinese policymakers’ perspective.

03:05

What happened at the Chinese Communist Party’s major policy meeting, the fifth plenum?

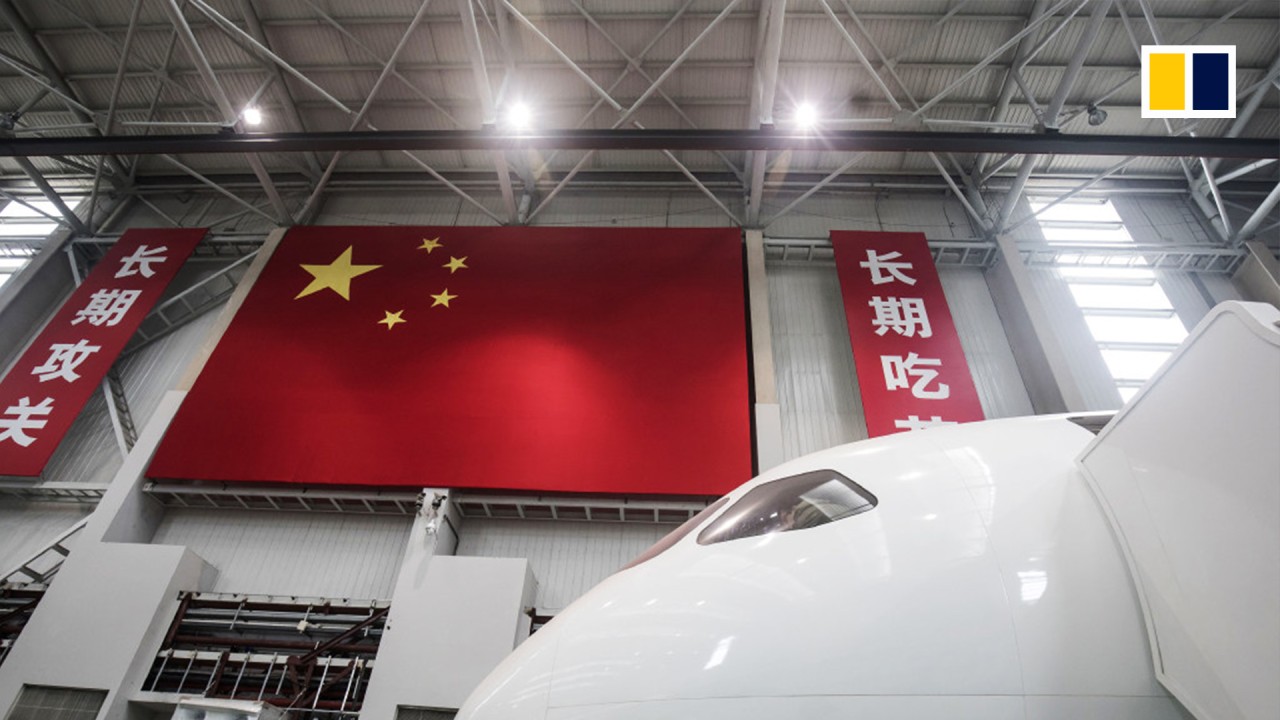

There are three keywords in the new five-year plan. The first is “self-reliance”. During this five-year plan, China will speed up its promotion of a new development pattern in which domestic and foreign markets boost each other while the domestic market remains the focus.

The US has also made dramatic changes in its approach to China and highlighted the importance of containing China’s rise. As such, China’s renewed focus on promoting domestic development suggests it is preparing for a protracted struggle.

01:56

What’s the beef with the ‘Made in China 2025’ strategy?

According to a communique released after the plenum, the real economy must remain China’s focus for economic development, and it must build itself into a manufacturer of quality while enhancing its strength in cyberspace and digital technology. By making breakthroughs in core technologies in key areas, China will become a global leader in innovation.

The US-China conflict in the past few years has led Beijing to realise that dominance in core technologies is crucial to secure the upper hand. China’s weakness in innovation is a key reason its total factor productivity has steadily diminished in the past decade. Instead, investment has been the primary contributor to economic growth, resulting in growing debt levels which subsequently raise risks in the financial system.

In recent years, Beijing has moved away from setting an explicit growth target, and policymakers appear to have brought this approach into the new five-year plan. However, China still has big ambitions; its leaders have projected that the country’s per capita GDP will reach the level of moderately developed countries by 2035.

Extrapolating from linear GDP projections, China’s level of nominal GDP is likely to surpass that of the US some time between 2025 and 2030. As a result, how best to deal with China’s rise will remain an important theme for Western countries.

China has laid out its new strategic framework in its latest five-year plan as a response to changing geopolitical dynamics. There is little doubt that this strategy will face strong headwinds. There are also tremendous uncertainties about the world after Covid-19, which suggests the road ahead will be bumpier than many expect.

Hao Zhou is senior emerging markets economist at Commerzbank