How Britain’s CGTN ban shows Western insecurity over China’s rise

- Cold War parallels are imperfect, but one area where significant competition already exists and could spiral out of control is the battle to assert the ‘truth’

- The UK’s ban of a Chinese state media outlet is a sign of deeper change and fear that China’s authoritarianism gives it an inherent advantage in a battle for the ‘truth’

However, whereas many of the arguments about the emerging new cold war speak of increasing military and economic tension like in the original Cold War, the current international climate is significantly different from the initial post-second-word-war setting.

For a start, there is significant trade interdependence and financial interaction in China’s relationships with the United States and European Union, whereas nothing similar existed between the Soviet Union and US at the onset of the original Cold War. Furthermore, US military supremacy, coupled with the existence of nuclear weapons on both sides, renders great power military conflict unlikely.

However, there is one area where significant competition already exists and, judging by recent events, could spiral out of control – the battle in asserting the “truth”.

02:25

China bans BBC World News over Xinjiang report and after China state broadcaster loses UK licence

Truth is inextricably linked with power and politics. As political theorist Andreas Nohr notes, the politics of truth is “the struggle at the most general level of society where the true is separated from the false and where what gets to count as truth and reality is decided”. Modern societies have evolved to a point – largely because of the advent of science – where the space for difference in thought is more limited.

Thanks to the technological advances brought by the digital revolution, namely the creation of the internet and cyberspace, competing over truth has become far more hotly contested than ever before. This is partly because, in cyberspace, given the lack of clear sovereignty or territorial integrity, the state’s power in constituting truth is weakened and open to infiltration by corporations or foreign powers.

02:24

China attacks BBC a day after UK revokes licence of Chinese state broadcaster CGTN

Yet, the UK’s decision should not be just read as a tit-for-tat measure designed to level the playing field. It is also a sign of a deeper change in British governance, one which is likely to be mimicked across the West.

However, as Western models of democracy and capitalism have suffered serious reputational shocks, both externally and internally, during the past decade and a half, there is a lack of confidence in many states that the “truths” they govern by are as robust as they once were. In other words, countries such as the UK are suffering from a diminishment in their ontological security – a collective sense of continuity and order in events.

01:51

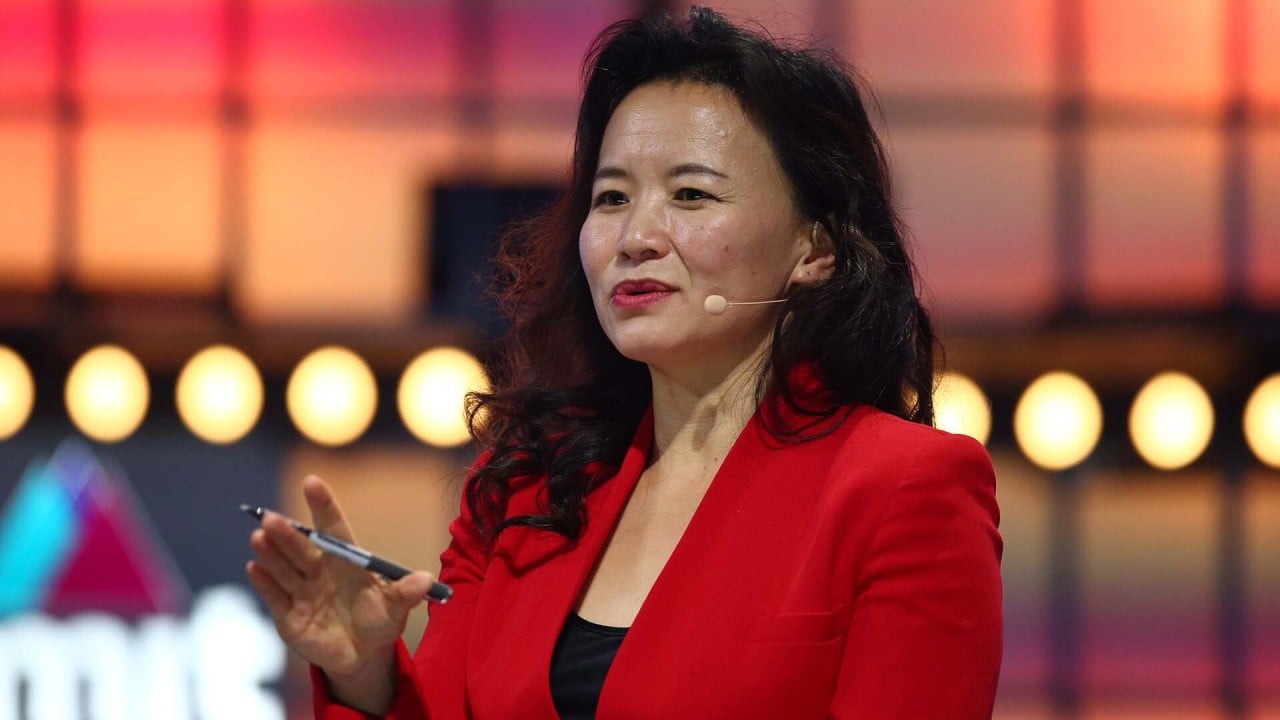

Australian journalist Cheng Lei formally arrested in China for ‘illegally supplying state secrets’

For policymakers in the UK and the broader West, the fear is likely to be that China’s authoritarianism gives it an inherent advantage in a battle of truths. Western powers cannot hope to infiltrate China; China can infiltrate the West.

The problem is that banning Chinese state-owned entities involved in asserting China’s version of the truth could have a “Streisand effect” (when an attempt to hide, remove or censor information unintendedly further publicises that information).

It could also further decrease their already-depleted levels of ontological security, all the while distorting the perceived threat of China. This could, in turn, lead to more excessive measures and a further diminishment of ontological security.

Ruairidh J. Brown is a lecturer in international studies at the University of Nottingham Ningbo, China. Nicholas Ross Smith is an associate professor of international studies at the University of Nottingham Ningbo, China