In making US supply chains stronger, Joe Biden’s policies may end up looking more like Donald Trump’s than Barack Obama’s

- Expect more reshoring to protect American worker interests, and greater regionalisation with partners such as Colombia or Mexico preferred over those in Asia

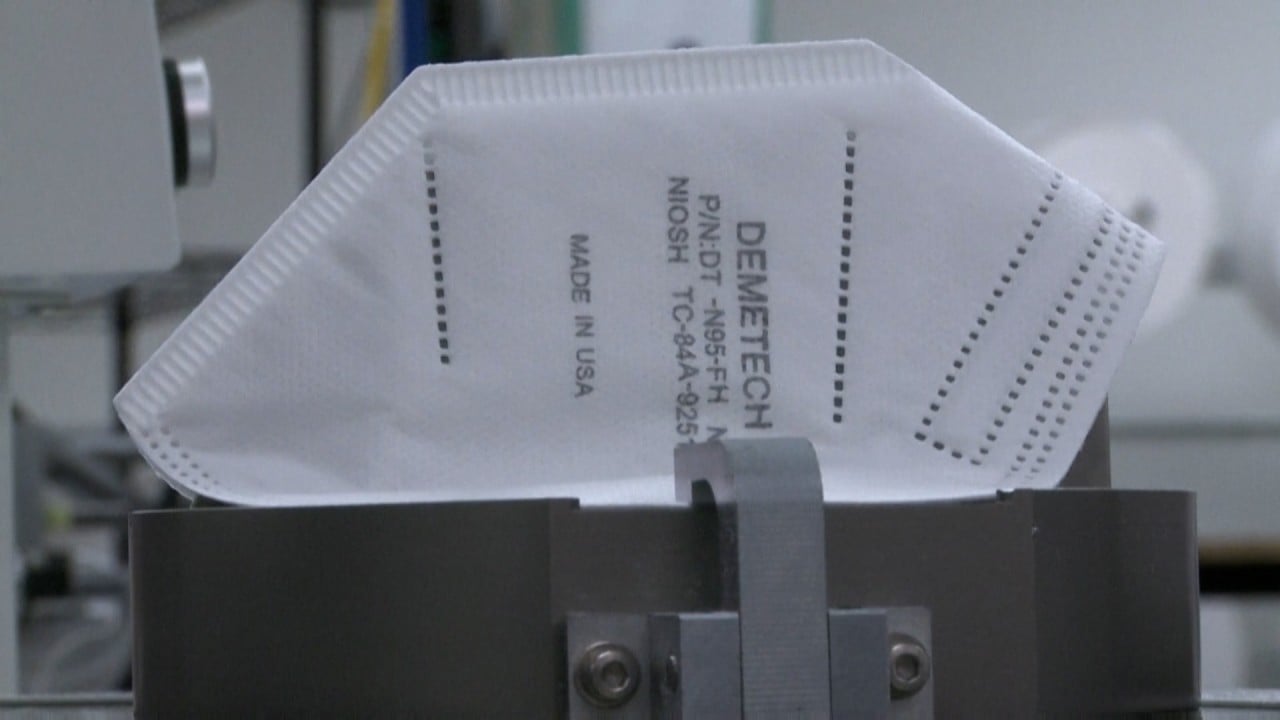

The move had been anticipated, as Biden had pledged during the presidential campaign to address vulnerabilities in the US supply chain that had become glaringly evident during the pandemic.

Broadly speaking, the review is certain to conclude what has become apparent: that the United States is too reliant on foreign countries in at least some areas, and that many supply chains lack sufficient resiliency to cope with environmental or public health disruptions.

These conclusions will only reinforce Biden’s core belief that the US needs to pursue a US worker-centric approach to trade. The net result will be trade policies and domestic initiatives (such as financial incentives and procurement regulations) designed to encourage production in the US and discourage reliance on extended supply chains.

Although Biden’s election elicited a sigh of relief from US trade partners who viewed four years of Donald Trump as an assault on free trade – and hoped to return to previous norms under Biden – some of the new president’s policies will resemble those of his predecessor.

Biden has made it clear that he will not return to the full-throttled philosophical embrace of free trade that characterised US policy from Truman to Obama. The resulting pro-free-trade policy environment facilitated the creation of extended global supply chains constructed almost entirely on the basis of achieving the greatest economic efficiencies.

This “economics textbook” belief in the benefits of trade across highly specialised, far-flung supply chains had been broadly accepted for decades but is now being questioned.

The middle class and non-college-educated workers in particular have been devastated by import competition and simply never recovered. Credible academic research (such as by Massachusetts Institute of Technology economist David Autor) showed that trade-displaced workers suffered from higher unemployment and lower wages for a decade or longer after the initial dislocation.

And significant social maladies, such as opioid and alcohol addiction, rising crime and crumbling communities, are increasingly associated with trade dislocations.

Although Trump’s confrontational trade policy and use of unilateral (and frequently dubious) tariffs raised the ire of the international trade policy community, there was also widespread acknowledgement that many of his trade complaints were legitimate.

A more critical eye was cast on the mistakes made about trade in the past and a growing consensus emerged in Washington that the US must fundamentally reorient its approach.

Biden’s desire for a worker-centric trade policy reflects this view. Instead of being driven by corporate agendas, the interests of workers will now be prioritised in trade policy. American citizens will be viewed as wage earners rather than consumers seeking the lowest price.

Biden must act on his window of opportunity on trade

Trade policy will be driven by a radically different philosophy: if Americans have to pay a little more for T-shirts or microwave ovens, that is perfectly fine as long as it helps rebuild the middle class, puts the average US worker on a firmer financial footing and strengthens communities.

This could shift previous calculations that had precluded production in the US and which are likely to be accentuated by technological advancements in manufacturing that further favour production in the US.

At the same time, though, Biden administration officials have no delusions of autarky and recognise that viable supply chains will necessarily include foreign production.

However, there will be a strong preference for foreign production to be brought closer to home and preferably to like-minded partners rather than geostrategic rivals.

As a practical matter, this means that countries such as Colombia or Mexico will in some cases be preferred over Asian partners for production that cannot take place in the US. We should anticipate policies to support that preference, and potentially an increased regionalisation in supply chains.

The Biden administration has embarked on its 100-day supply chain review. As a sign of how fundamentally the trade landscape has shifted in the US, the resulting policies might have more in common with the Trump administration he defeated than the Obama administration he served.

Stephen Olson is a research fellow at the Hinrich Foundation