Could New Zealand champion a new non-aligned movement to avoid US-China cold war?

- US-China tensions are leading several countries in the Indo-Pacific to seek a third alternative to getting caught up in a great power struggle

- Malaysia and Indonesia are obvious candidates to lead such a movement, but New Zealand could be a dark horse given its independent foreign policy

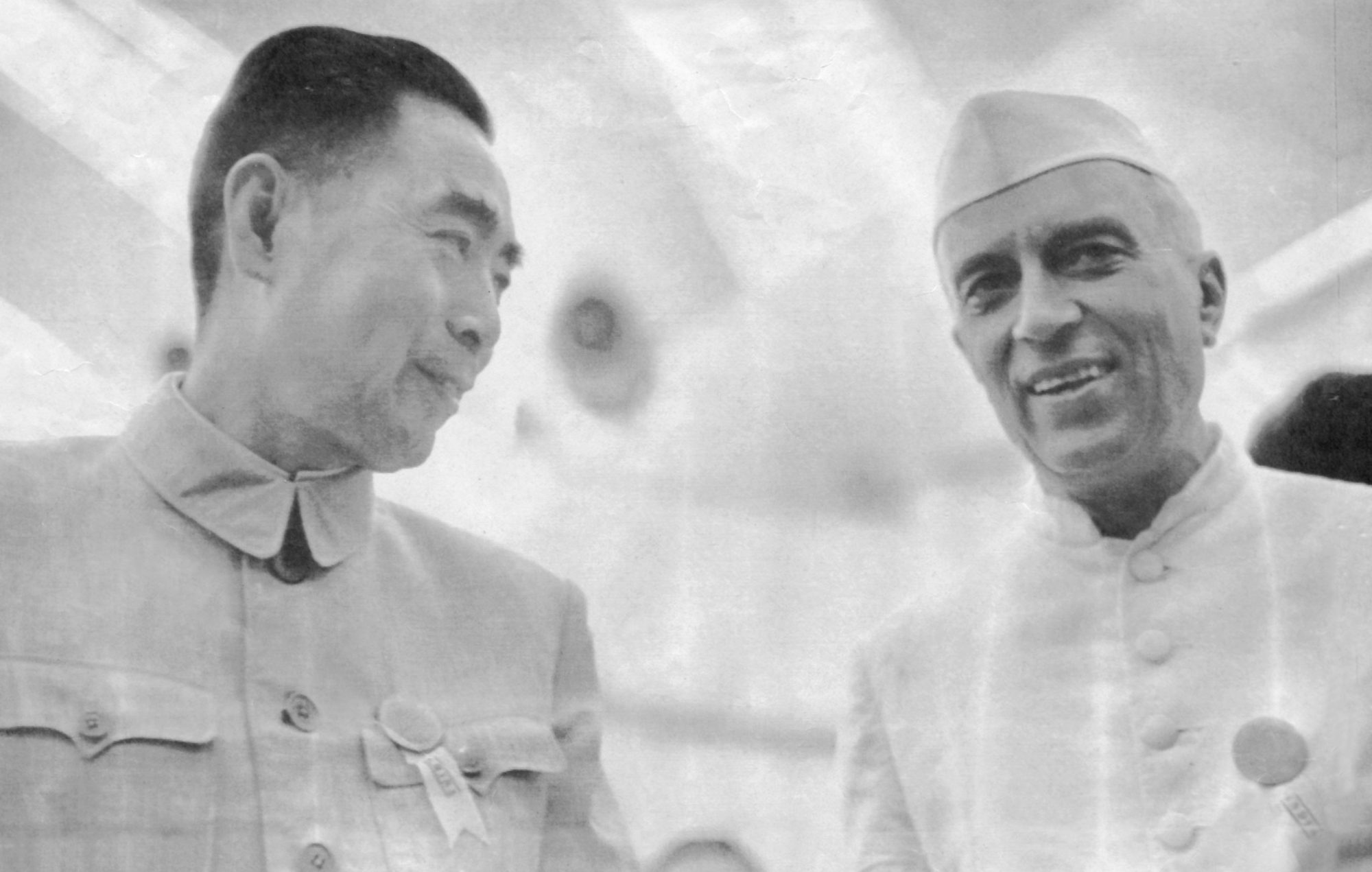

Yugoslavian president Josip Broz Tito was the architect of the meeting. He was joined by four other key figures – Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser, Indian prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru, Indonesian president Sukarno and Ghanaian president Kwame Nkrumah.

The geopolitical situation at the time provides important context for why this meeting was conducted with such urgency. By 1961, it was clear the relationship between the United States and the Soviet Union was deteriorating.

Further, with the onset of decolonisation in Africa and Asia, the Cold War became a truly global phenomenon as both the Americans and Soviets ramped up competition in these newly formed states.

Tito’s pathway to embracing non-alignment was more by accident than design. At the end of World War II, the expectation was that Yugoslavia would align itself closer to Moscow than Washington since it was a socialist country.

This was initially the case as Yugoslavia was a keen participant in Moscow’s post-war-order building. Belgrade was even chosen as the headquarters of the Information Bureau of the Communist and Workers’ Parties. However, Tito’s personality, independence and ambition irked Soviet leader Joseph Stalin, and in 1948 he excommunicated Tito and Yugoslavia from the Soviet international order.

Stalin’s betrayal elicited significant shock and consternation in Belgrade. Yugoslavia, out of desperation, sought help from the US and was able to avoid immediate economic ruin and political collapse.

Until Stalin’s death in 1953, Yugoslavia walked a tightrope. Stalin was enraged by Yugoslavia’s dealings with the US and contemplated invading in 1951. But Yugoslavia also came under pressure from the US to align itself more westward.

The success of the non-aligners was patchy. Yugoslavia and India were able to pursue consistent non-alignment for most of the Cold War. Others such as Egypt, Ghana and Indonesia succumbed to internal instability. Yet, the notion of non-alignment remained an ideal many countries aspired to during the Cold War.

The end of the Cold War saw the Non-Aligned Movement fall into irrelevance. The institution still exists and has 120 members. Regular conferences and summits take place, but it no longer holds the international weight it did.

Just as with the original founding of the movement, it is imperative that new leaders emerge to create a credible and galvanising movement. Given that any new cold war will be centred on the Indo-Pacific region, several countries there have already shown a desire to avoid being embroiled in the rising tensions.

New Zealand strongly identifies as a principled, independent national actor. Ardern has also proven adept at statecraft, becoming arguably the most internationally well-known New Zealand leader of any era.

Whether New Zealand is bold enough to spearhead a new non-aligned movement is debatable. However, the fact remains that non-alignment will become an attractive option for many of the smaller countries caught in the middle as Sino-US relations continue to deteriorate.

But, as the original movement showed, leadership and friendship are essential elements in making such a movement work. Who will be the 21st-century’s Tito, Nasser, Nehru, Sukarno and Nkrumah?

Nicholas Ross Smith is an adjunct fellow at the University of Canterbury, New Zealand