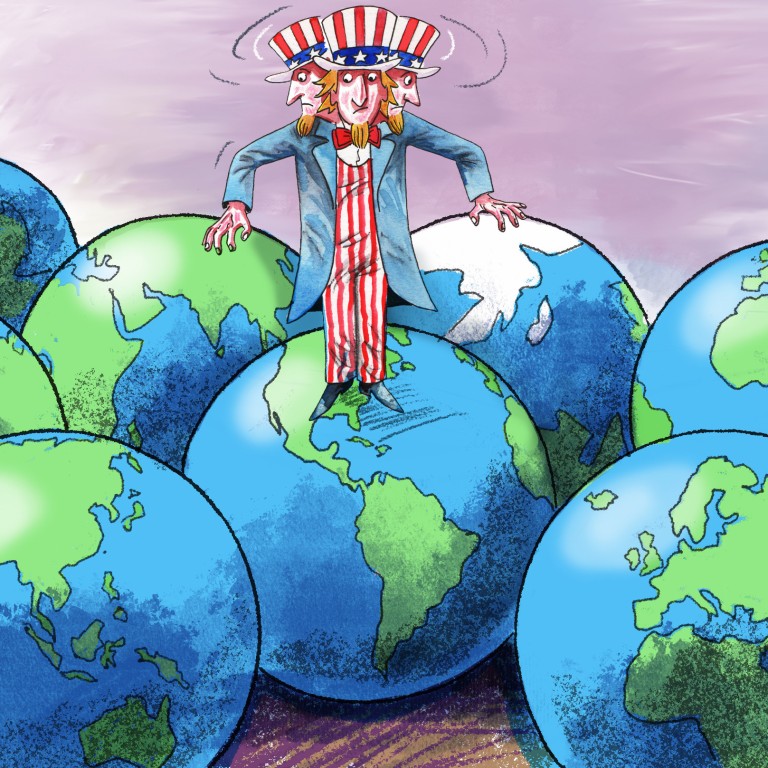

How American hubris is hastening the decline of US-led global order

- As Washington tries to contain both Russia and China, it faces an increasingly war-weary Europe and a developing world reluctant to take sides

- America’s own social and political rifts and broken infrastructure are causing some to question its entitlement for calling the shots in an increasingly multipolar world

Defending its global hegemony, the United States is now fighting a global war on two fronts, against Russia and China simultaneously.

Speaking to Foreign Policy, Fiona Hill, a top Russia adviser to three US presidents, urged the world not to buy Moscow’s claims that it would outlast the West in Ukraine, mindful of societal hardships in the country and Putin’s hopes of a 2024 re-election.

However, Andrei Kolesnikov from the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, believes that the Russian people have generally adapted to the new reality over Ukraine, and remain ideologically supportive of Putin.

Meanwhile, the initial enthusiaism with which Europe rallied around US leadership is beginning to wane. Energy and food shortages are kicking in, amid broken supply chains, raising the spectre of inflation levels not seen in decades.

A rapidly-rising China, however, remains unfazed, and for good reason – 10 good reasons, in fact.

First, the vast majority of countries in Eurasia, Africa and Latin America do not want to be forced to choose between the US and China. After all, 130 nations across the globe count China as their largest trading partner, compared with 57 for the United States.

What is more, the PGII has nothing to show for itself regarding the critical need for infrastructure in the developing world. It also relies heavily on the private sector in areas not noted for commercial attractiveness.

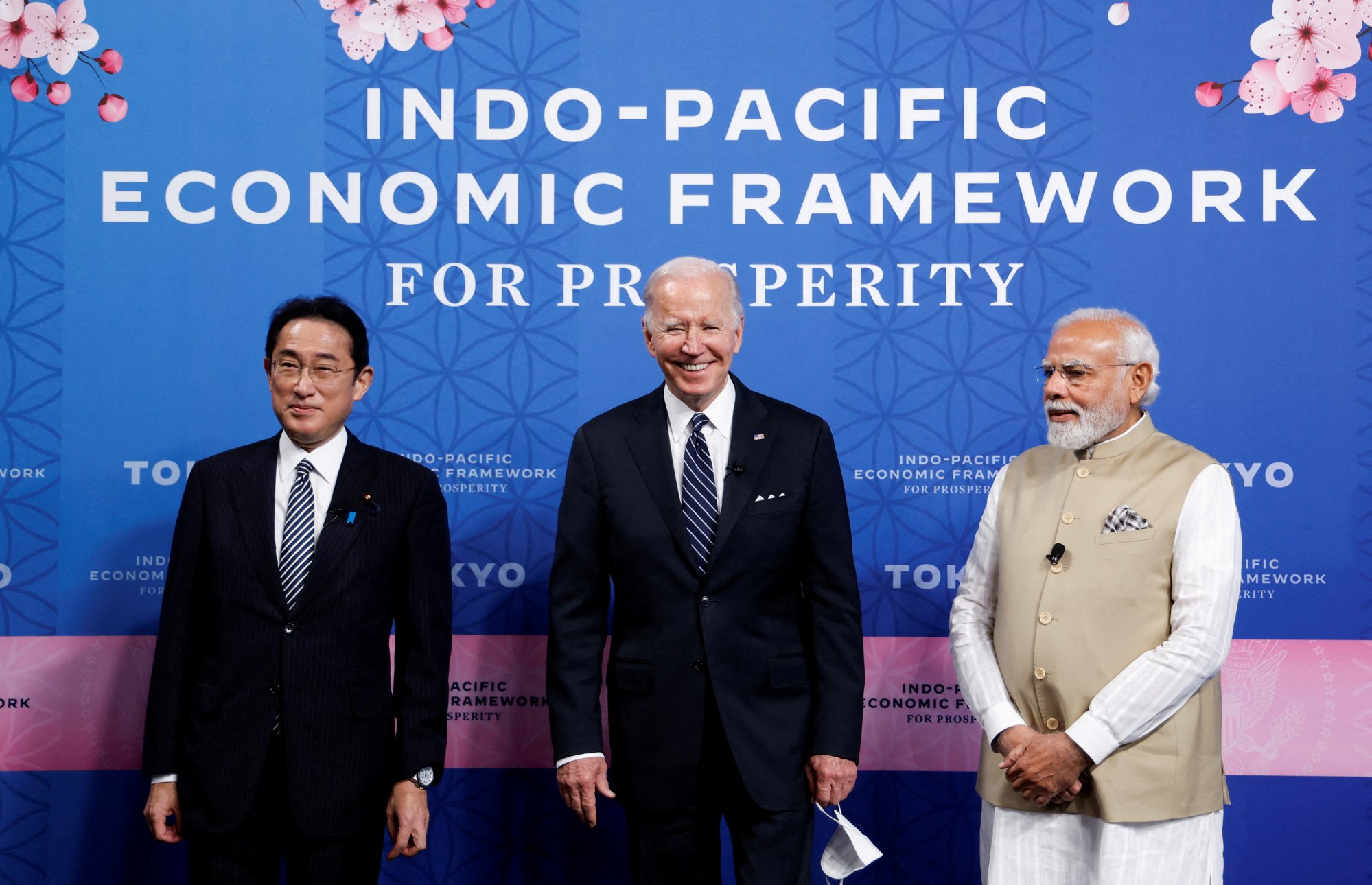

In response to the RCEP, Washington has come up with a larger Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF), touted to include most of the RCEP’s US-friendly member countries, and to press for higher standards for trade, digital connectivity, supply chain resilience and infrastructural investments.

Almost like waking up after a long sleep, US Vice-President Kamala Harris was hurriedly dispatched to speak at a Pacific Islands Forum in Fiji, promising US$60 million in development aid over 10 years for climate change mitigation, measures against illegal fishing and preservation of ocean ecology.

The idea is to promote “South-South” cooperation between developing countries, embracing existing trade partnerships in Latin America, South Africa and Asia.

Finally, the US penchant for coercive and divisive tactics, hypocrisy, double standards and indiscriminate dollar weaponisation have stoked much resentment and anger. Its domestic sociopolitical rift and broken infrastructure are making some question its entitlement for calling the shots in a world that is fast becoming more multipolar.

Former British prime minister Tony Blair recently remarked that the Ukraine war shows the West’s dominance is coming to an end as China rises. He appears to be spot on.