As China’s jobless youth liken themselves to Kong Yiji, Beijing’s tone-deaf response is not helping

- With youth unemployment hitting a record high in China, some jobless graduates are using a 1919 story to express their frustration

- The authorities have responded with critical articles on the negativity of young Chinese, when much more needs to be done

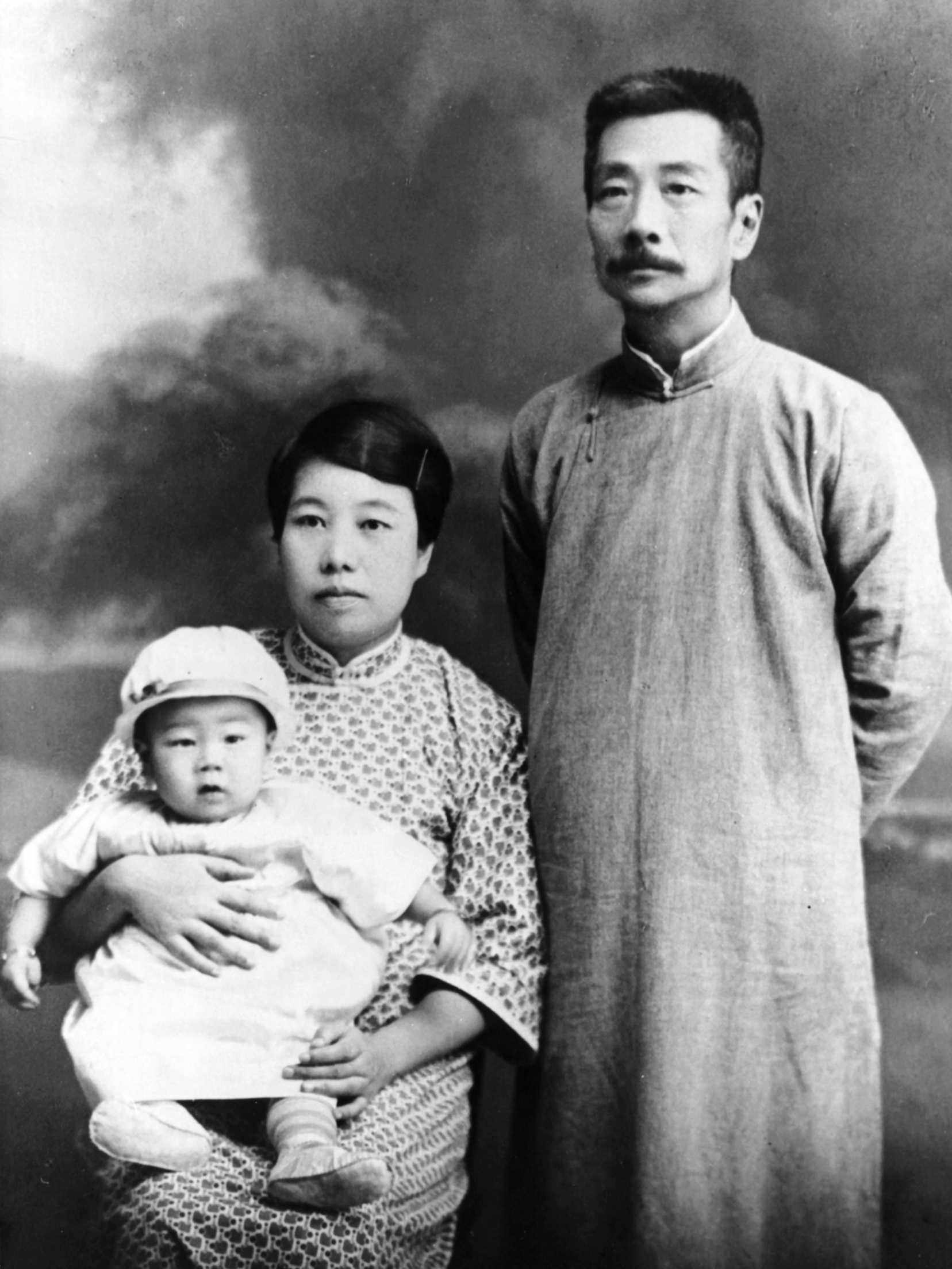

The character of Kong Yiji, a pathetic scholar who fails the imperial examination and struggles to make a living, appeared in a story by literary great Lu Xun first published in 1919. A century on, the character is being dusted off and rediscovered in China by educated, unemployed young people.

Some of these unemployed graduates have started to identify with Kong Yiji, who in the story wears the long gown of the educated elite and clings to his image as an intellectual who works with his brains, not his hands.

In February, an online post titled “Academic qualifications are not only a stepping stone, but also a pedestal I can’t step off, and the robe Kong Yiji can’t take off” sparked a heated debate about the struggles of both the character and China’s educated youth.

On social media, some young people have vented their frustration, likening their plight to Kong Yiji’s.

The authorities haven’t turned a blind eye to this. In March, a commentary on the website of CCTV, China’s state broadcaster, criticised the negativity surrounding “Kong Yiji literature”. The tragedy of Kong lies in his unwillingness to take off his scholar’s robe – which had become the “shackles on his heart” – and work hard to turn his life around, the piece said. It called on Chinese youth not to be trapped in their robes like Kong.

In a similar piece, the Communist Youth League urged young people to roll up their sleeves and do whatever jobs they could get their hands on.

How the ‘lying flat’ generation can push China towards common prosperity

The condescending tone of these articles, which seem to pin the blame on young people and imply they simply lack the courage to face reality, hasn’t gone down well with many who are already anxious about their job prospects. Some netizens retorted that members of the Communist Youth League should give up their jobs and work as cleaners instead.

Such messages from the authorities are unhelpful. They don’t seem to recognise the enormous challenges faced by young jobseekers. Currently, China’s education system, economic environment and job market are far from ideal.

Those without power and connections really struggle to find employment. Besides, there is not much of a social welfare system for the unemployed to fall back on. It’s little wonder many feel anxious, depressed, even desperate. It is understandable that some are releasing their tension in harmless ways, by jokingly comparing themselves to Kong Yiji.

Unemployed young people could feel scarred by their failure to find suitable work and might perceive their future to be dim. Social unrest could follow.

Such efforts are commendable, but much more needs to be done. Naturally, it is not feasible for the government to find a job for every graduate. Scanning the internet, one gets an overwhelming sense of helplessness. “Young people need understanding as well as encouragement,” says one post.

If the authorities continue to blame the youth for soaring unemployment, there is a danger that some of them might become like another Lu Xun character, Ah Q, who is synonymous with the ability to convince oneself of one’s “spiritual victory” over an otherwise insurmountable challenge.

Lijia Zhang is a rocket-factory worker turned social commentator, and the author of a novel, Lotus