BRICS bloc has come a long way but it is not a world power, yet

- While the grouping is undoubtedly growing in relevance, an impressive GDP alone is no measure of global power and BRICS nations still trade more with the G7 than each other, in a world dominated by the dollar

But beyond the kudos each country might receive, the implications for the global balance of power is, at the moment, quite limited.

Having a strong economy is useful in acquiring power in international relations, but to say this milestone represents an epochal change of global power grossly exaggerates the importance of gross domestic product on purchasing power parity terms, or GDP (PPP).

First, GDP (PPP) is a misleading statistic to use in measuring international power as it calculates GDP relative to the cost of living in a country. When judging power, GDP in current US dollars is much more useful because it reflects current market prices. A vastly different picture emerges using this measure, with the BRICS grouping’s GDP (US dollars) at US$24.7 trillion vs the Group of 7’s US$42.7 trillion, according to the latest World Bank data.

Thus, GDP alone – whether in PPP terms or in current US dollars – tells us very little about how much economic power a country might have. Furthermore, non-state actors such as multinational corporations are also extremely important influencers in this system.

A third factor which severely limits the persuasiveness of the argument that an epochal change of global power is happening is that neither BRICS nor the G7 is a closed economic bloc. Rather, they exist within a broader international financial and economic system. Comparing the two really makes no sense beyond trying to make a cheap geopolitical argument.

In any case, BRICS is much more of a political grouping for now than an economic one.

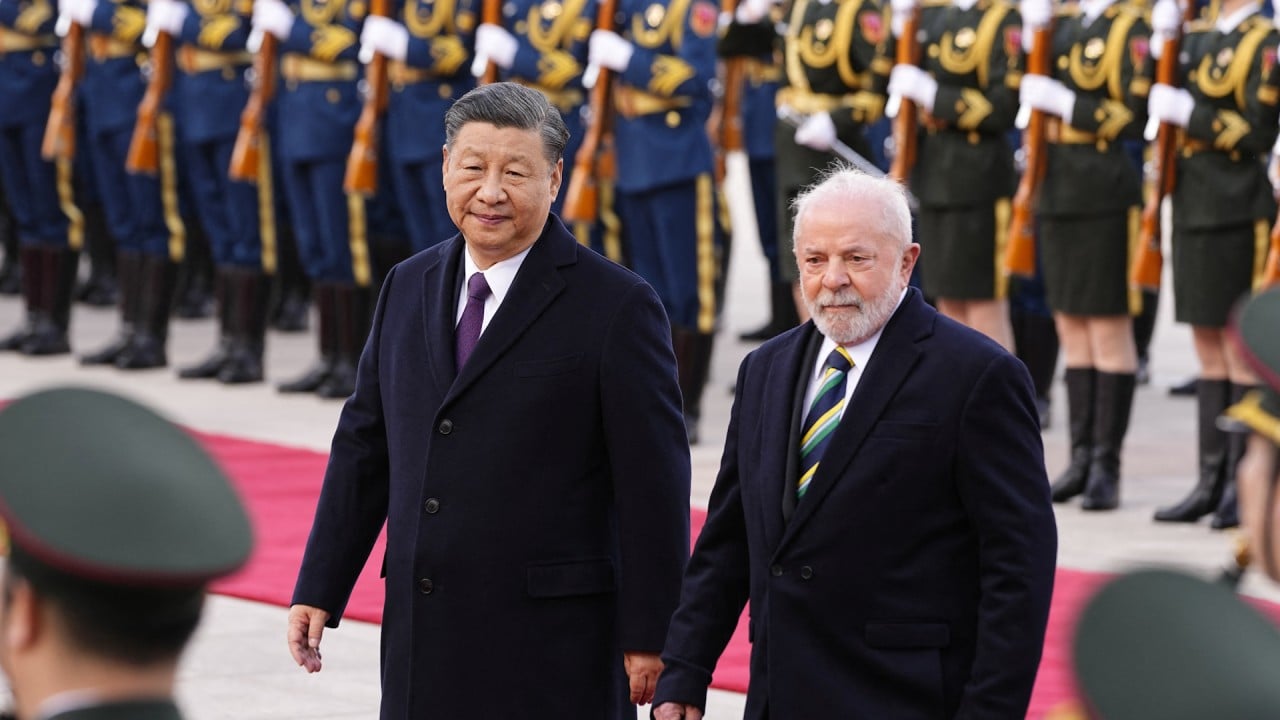

Take China for example, undeniably the lead economy of the BRICS bloc. Yet, from an international relations perspective, China is far more involved economically with G7 countries than the rest of BRICS. It sells around 27 per cent of its exports to the G7 and a mere 7 per cent into the BRICS area.

The picture is similar in the rest of BRICS. India and South Africa also export more to G7 countries than to the BRICS area. Even Russia, which has had a critical disjuncture with the West, still exports slightly more to the G7 countries than BRICS. Brazil is the only country that bucks this trend.

But as Michael Pettis, a finance professor with an expertise on China, argues, China is not in a position to challenge the dollar. As a surplus economy, China depends on large deficit economies like the US. Also, allowing the yuan to become a reserve currency entails a serious relaxation of financial control, something the Communist Party is unlikely to want to do.

Pouring cold water on the purported global economic challenge posed by BRICS should not be taken as a rejection of the bloc’s influence in international relations, however. Five years ago, many analysts were proclaiming the grouping to be dead but it has shown much resilience and clearly, in the wake of the Ukraine war, the group is galvanised and more committed to the idea of challenging America’s privileged global position.

Ultimately, one does not need to embellish the financial and economic strengths of BRICS to make a point that the group is growing in relevance. It is also an indication that, although in strict power terms, the international system remains resolutely unipolar, in political terms, it is moving towards one where multiple international orders exist independently at the same time.

Nicholas Ross Smith is an adjunct fellow at the University of Canterbury, New Zealand