Little hope of progress on US-China military talks when two sides remain so far apart

- Even with better communications between their respective militaries, the trust gap between Beijing and Washington is unlikely to improve

- US calls for military transparency might sound reasonable, but they favour the more powerful nation and come from a side failing to practise what it preaches

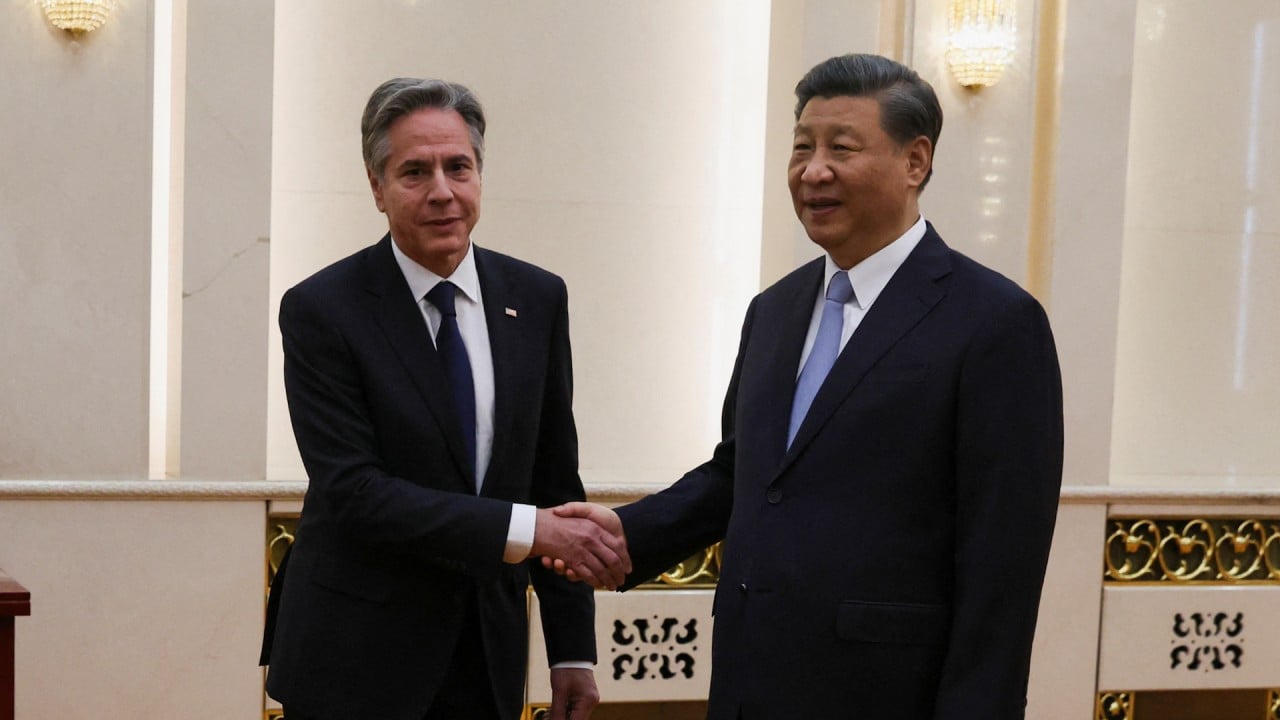

The US wants to reestablish communications to help tamp down the possibility of conflict, but China is not cooperating. As pointed out by Yun Sun, a senior fellow and co-director of the East Asia Programme and director of the China Programme at the Stimson Centre, its position on restarting military dialogue might be part of a strategy that encompasses the communication process.

Realpolitik is influencing the efforts at talks. China wants the US to demonstrate good faith with its actions, not just its words. It seems that every opportunity for meaningful talks is preceded, followed or even accompanied by aggressive or negative action on both sides.

Even with better communications between their respective militaries, the trust gap between China and the US is unlikely to improve and dangerous incidents are still likely. This is because they do not stem from misunderstandings and miscommunications but are rooted in deeper differences about the international order and strategic interests. As such, the best outcome of talks would be to manage these incidents when they occur.

The two sides have stated their fundamental policies regarding their relationship. President Xi Jinping has proffered “three noes”: China “does not seek to change the existing international order or interfere in the internal affairs of the United States and has no intention to challenge or displace the United States”.

Xi has proposed “a new model of great-power relations” that implies equality and shared responsibility in world affairs. But, so far, it seems that the US has rejected this notion, and expecting that to change soon is unrealistic.

Besides, the notion of transparency is ambiguous. The US says it is transparent, but try to ask questions about the position and role of its nuclear-armed submarines or its specific intelligence collection capabilities in the South China Sea.

Until the “noes” on either side begin to ring true, there will be little progress on meaningful military -to-military communications and tension will remain high in the South China Sea.

Mark J. Valencia is a non-resident senior research fellow at the Huayang Institute for Maritime Cooperation and Ocean Governance