US-China rivalry and the danger of using history to justify moral right

- Both have been known to use history such as the Cold War and the Eight-Nation Alliance to bolster their positions and criticise the other side

- The risk is that the US could end up feeding China’s narrative of Western imperialism, bolstering Communist Party legitimacy and narrowing the scope for de-escalation

However, an overlooked aspect of the growing US-China tension in the Indo-Pacific is how history is being used to justify and critique policies.

The report in part justifies US involvement in the Indo-Pacific through the selective use of history; placing America as the key actor in creating peace and stability in the region in the 20th century.

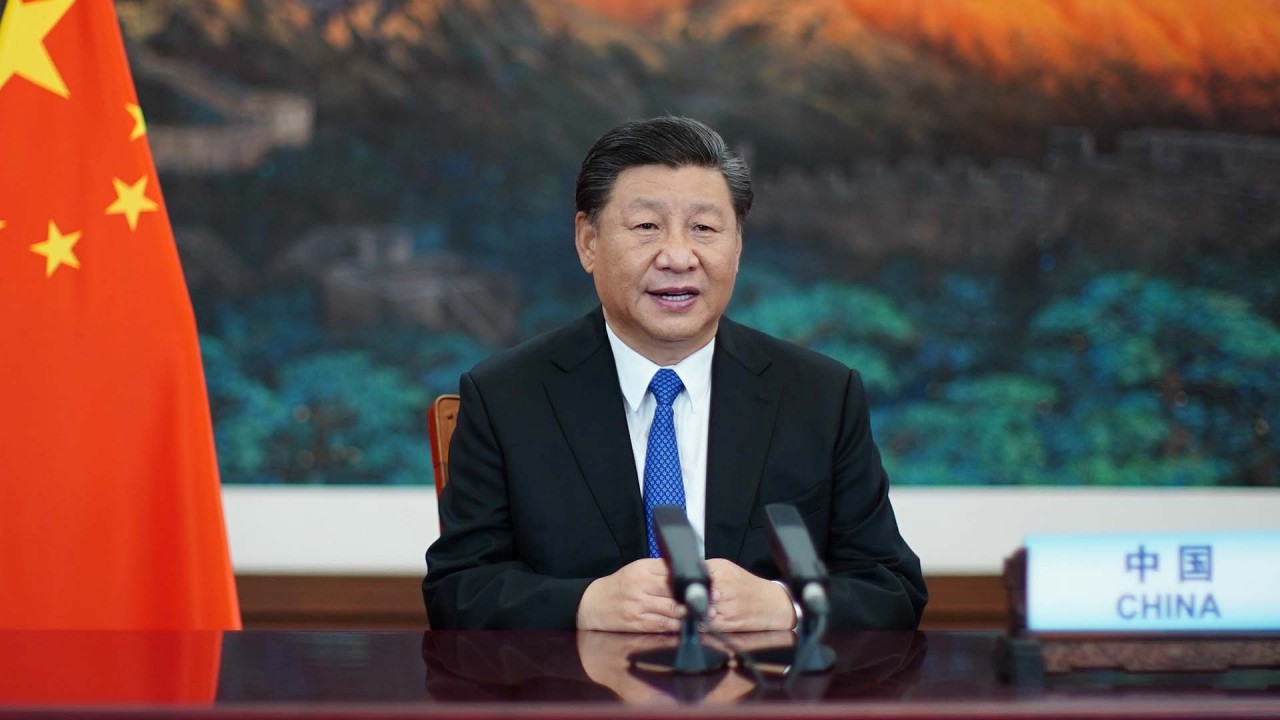

China also uses history to critique US policies. For instance, on the day of the Aukus announcement, China’s foreign ministry spokesman Zhao Lijian derided the military alliance as the product of an “outdated Cold War zero-sum mentality and narrow-minded geopolitical perception”.

The Cold War has become a popular historical analogy in China’s critiques. In stark contrast to the US narrative, China recalls the US and its Cold War allies as being fixated on containing Communism and pursuing international domination.

In invoking this analogy, Beijing is casting the US as seeking to maintain international dominance (by keeping China down) while China represents a country more interested in global cooperation and deepening trade relations.

This analogy has yet to be officially referenced in response to Aukus (although it has appeared on Chinese-language social media), but has been used many times by Chinese officials this year.

China’s use of history in this way has a twofold purpose. It presents the US (and its allies) as pathologically imperialist by highlighting the negative past, while also highlighting that China “is no longer what it was 120 years ago”.

In other words, the Communist Party has presided over the rise of China from a humiliated international afterthought into a superpower that can no longer be bullied.

To this end, “vulgar” strategic announcements, such as with Aukus, play into China’s hands as they help to add fuel to its victim-playing. Although US-led initiatives – like Aukus – may be narrowly defined and defensive-oriented pacts, the optics can be easily skewed to validate China’s claims of representation of imperialism.

Recall Mao’s famine, forget Churchill’s: how the West captured Asian minds

Thus, beyond the real-world implications of the deterioration of the Sino-American relationship, the increased use of history by both sides to justify or critique policies represents a kind of ontological competition. Both sides are asserting their versions of the truth.

China is positioning itself as the one to bring peace and stability: “Facts have proved that China is not only the main engine driving economic growth in the Asia-Pacific region, but also a staunch supporter of regional peace and stability,” said Zhao. “China’s development is a growing force for world peace and good news for regional prosperity and development.”

Ultimately, it is clear that China’s rise and growing assertiveness in its regional backyard is causing significant fear (and perhaps, some paranoia) in many countries. Formulating long-term strategies to alleviate this is important.

But the problem with the efforts by the US and its allies so far is that not only might they not be strategically well thought-out, they could also add fuel to the fire of China’s grievance rhetoric, bolstering the Communist Party’s legitimacy and narrowing the potential for de-escalation before a new cold war firmly takes hold.

Nicholas Ross Smith is an adjunct fellow at the University of Canterbury, New Zealand. Tracey Fallon is an assistant professor of China studies at the University of Nottingham Ningbo China