Joe Biden’s trade war with China is driving a wedge between the US and Europe

- Europe is pushing back against US demands for it to stop selling semiconductor technology to China

- Brussels’ insistence on setting its own trade terms with China is a win for Beijing – even if EU-China tensions persist elsewhere

The growing friction between the allies may allow Beijing to triangulate Brussels against Washington, especially given the economic interdependencies between Europe and China – but EU-China relations are fraught with tensions, too.

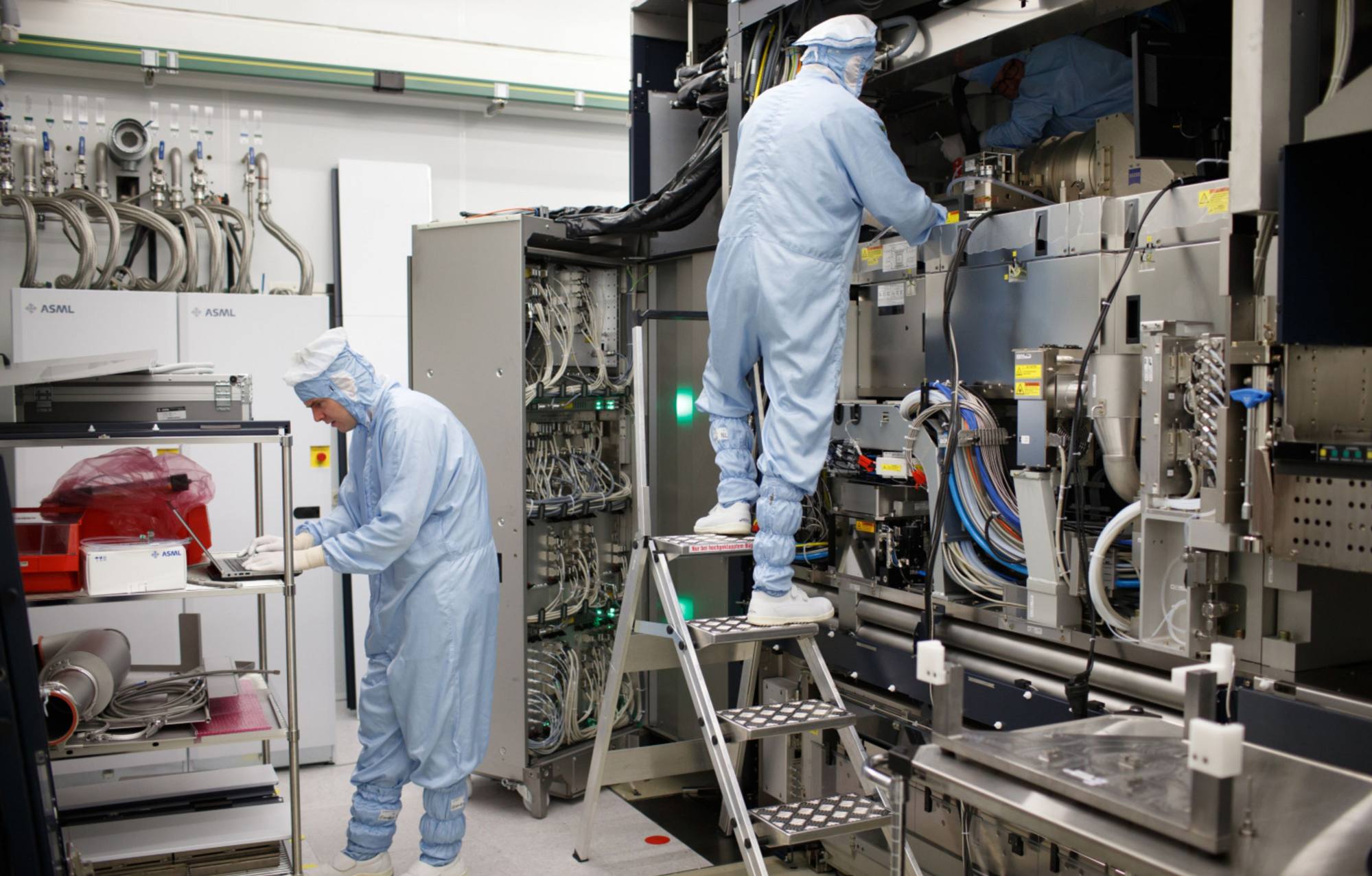

Earlier, in February, the European Union cleared a similar funding initiative providing 43 billion euros (US$46.6 billion) in aid to build plants in Europe. Brussels pointed to America’s control of 65 per cent of data processing revenues in expressing its mission to double the EU’s share of global chip manufacturing to 20 per cent by 2030. But it is now struggling over how to sacrifice other programmes to free up funding.

The ban and neo-mercantilism define a new era of relations among the world’s largest powers by positioning technological prowess as critical to defence preparedness. The policies also complicate diplomacy between the US and its allies.

Like others in Europe, Dutch economy minister Micky Adriaansens believes Europe and her country “should have their own strategy”. Stressing that relations with China are “very positive”, that the Netherlands does “a lot of business with China”, she insists that a European approach must take into account the risks to “specific products and value chains”.

China accounts for five per cent of Dutch exports and 11 per cent of its imports. For Europe as a whole, the value of goods the region trades with China reached 696 billion euros (US$754 billion) in 2021, up roughly 25 per cent from 2019, according to Eurostat.

China is the third-largest destination for EU goods exports, accounting for 10 per cent of the total, while also being Europe’s biggest source of imports, a 22 per cent share in 2021. Oil and natural gas shipped from Russia to China was diverted to Europe last year to narrow the demand-supply gap that drove up prices.

Officials and think tanks often say the interdependencies are “too big to fail”. These entanglements also give Beijing and Brussels leverage over each other, especially now, given the economic vulnerabilities challenging both regions.

But Brussels has issues with Beijing. “On the European side, market access is very open, whilst in China, several sectors remain much more closed,” Michel said. “We need greater reciprocity. We need a more balanced relationship.”

Europe must break with US to avert global economic disaster

All said, though, the efforts by Brussels and leaders of EU member countries underscore how Europe is broadening its “own” strategy towards China, with its pressure on Washington to allow flexibility on business with Chinese companies.

The dynamics are unfolding as they did when Henry Kissinger used triangular diplomacy during the Vietnam war by exploiting the rivalry between the Soviet Union and China, “pursuing strategic alliances or economic deals in an attempt to both weaken the hegemony of a powerful adversary and strengthen their own position”, as Kissinger wrote. This time, though, two close allies are involved.

James David Spellman, a graduate of Oxford University, is principal of Strategic Communications LLC, a consulting firm based in Washington, DC