China’s private firms shy away from bank borrowing, delaying investment

- Government efforts to boost bank lending to struggling private sector are getting lost in mixed messages and growing economic uncertainty

- Companies are postponing investment as they wait for outlook to clear

China’s private sector, the driving force behind the country’s economic miracle over the last 40 years, is struggling amid the Chinese government’s campaign to reduce national debt and the trade war with the United States. This is the second story in a series that will detail the challenges private firms face and outline the government’s attempts to address them.

Small business owner Philip Chen has never borrowed a penny from a bank, even during his darkest days back in 2003, when he had to turn to friends and relatives for the money to pay his employees’ salaries.

“It is super difficult for a small company to get a bank loan. The reality has always been like that. But, you know what, for now, I would not take a bank loan even if it is easy for me to get.

“Because, at this time in China, business expansion based on borrowing is suicide,” said Chen, who runs a cosmetics brand in Shanghai.

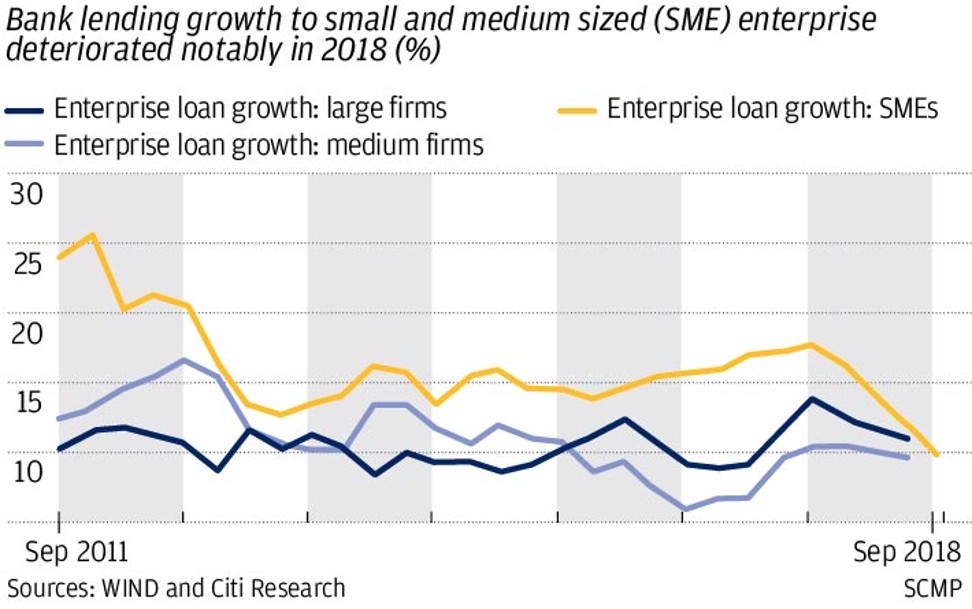

Chen’s experience underscores the difficulty Chinese small and medium-sized private businesses (SMEs) are having getting credit to start a new business, expand an existing business, or just continue operations during difficult economic times.

But it also highlights the growing reluctance of small firms like his to borrow for investment, given the increasingly uncertain economic outlook.

The ability of private businesses to access credit – and to borrow when loans are available – is critically important to the outlook for the Chinese economy, since it is the private sector which accounts for a majority of the nation’s economic activity and employment.

Since November, top Chinese leaders have made a point of stressing Beijing’s support for private ownership and small businesses.

The government has announced a series of steps to shore up the private sector, including easing capital requirements for commercial banks to boost lending, and creating new financing tools, including Credit Risk Mitigation Warrants (CRMW), to help bond issuance for private firms.

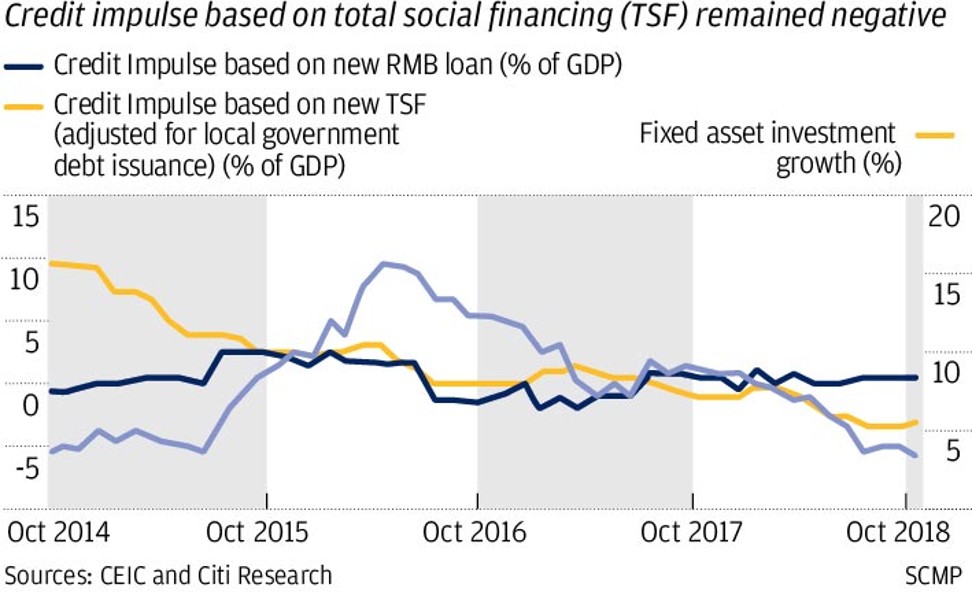

But the results so far have fallen short. Total social financing (TSF), a broad measure of credit and liquidity in the economy, has seen its year-on-year growth rate continue to slide, hitting a record low of 9.9 per cent in November, according to official data released last week.

The government’s own policies bear some of the responsibility.

For the past two years Beijing has been engaged in a campaign to deleverage the financial system, that is, to reduce indebtedness and eliminate riskier forms of lending.

This has reduced access to credit for small firms, as lending by non-traditional “shadow banking” sources have been dramatically curbed.

Recently, the government has changed its tune, urging banks to step up their lending to small private firms.

In an interview with state media last month, Vice-Premier Liu He, President Xi’s top economic adviser, stressed that it was “politically wrong” for bankers to shy away from lending to private companies, since they were a crucial element in the Chinese economy, accounting for 50 per cent of tax revenue, 60 per cent of growth and 80 per cent of urban employment.

Chinese financial regulators, including the central bank, are working around the clock to issue new measures and launch specialised funds to support private companies that are struggling to survive.

Trade war tightens credit for China’s small businesses, regulator warns

“To really solve the high cost and the difficulty [private firms have] in borrowing from banks … we are still a long way away,” Wang Zhaoxing, vice-chairman of the China Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission (CBIRC) said last month. “We need to work on it.”

To boost lending to the private sector, the government has sought to scale back the deleveraging push at the margins while maintaining its general thrust, so that the current focus on stabilising the economy in the face of the US trade war does not result in a further large increase in debt.

The result is a mixed message – increase lending but minimise risk – that has left many loan officers confused and has done little to promote new credit access.

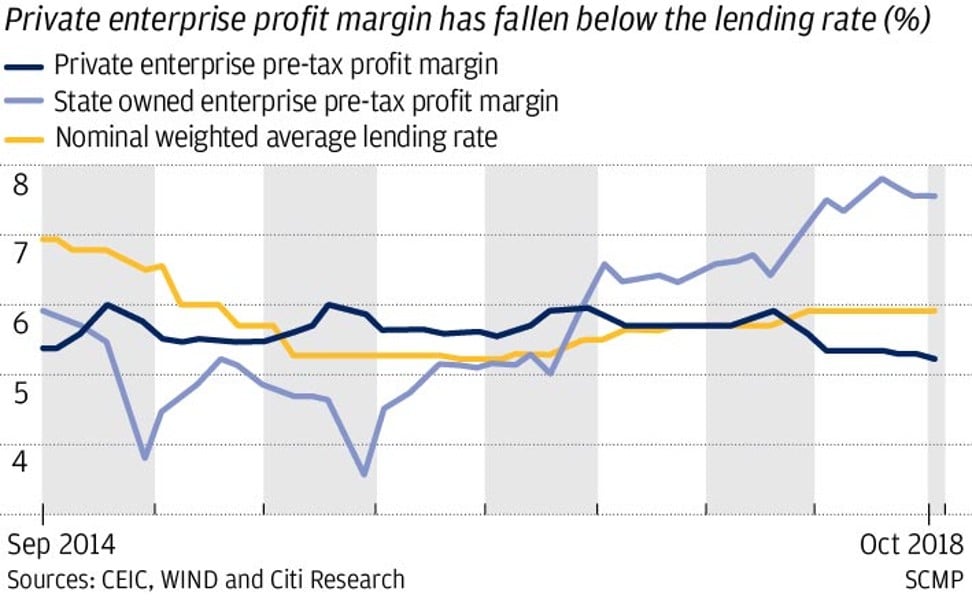

Lending to small private firms also suffers from a broad prejudice among loan officers, who favour lending to state firms due to the explicit government guarantee their borrowing carries. This bias is particularly acute at a time when private firms are at greater risk of credit defaults due to the slowdown in the economy.

The Chinese economic outlook is dim, at least for the next several quarters. And economists warn that the worst is yet to come. Business confidence in both the manufacturing and service sectors dropped sharply in October.

Industrial output and retail sales growth for the month of November both missed expectations, according to data from the National Bureau of Statistics, as the positive impact of front-loading orders – to avoid steeper duties imposed by the United States in the coming year – began to taper off and downward pressure on the Chinese economy increased.

Hunker down, wait for the storm to pass

Chen’s Shanghai-based company generated more than 30 million yuan (US$4.3 million) worth of revenue in 2017. Although orders for this year exceeded the capacity of his workshop, Chen decided to shelve a plan to expand his production.

“I have witnessed several friends fall into desperate conditions when banks suspended their loans this year,” Chen said, noting he had made up his mind to make do with existing capacity in the near future because of the uncertain outlook.

Wayne Wang, who runs a small trading company based in western China’s Sichuan province, shared Chen’s view.

Wang sold his garment factory back in 2003 to avoid rapidly rising land and labour costs. He said his new business was facing a contraction this year, as export orders are declining and “private lending is dying out” because of the government’s deleveraging campaign.

When they do borrow, private entrepreneurs are increasingly turning to semi-legal financial institutions for money.

These underground banks, usually funded by fellow private entrepreneurs, charge interest rates that are much higher than those of banks. But it is easier and faster to get the money, with few limitations imposed on how to spend it, Chen said.

Although the interest rate charged by underground lending platforms can reach an annual rate of 20 per cent or higher, it still makes an alternative for entrepreneurs in urgent situations.

No official figures are available on the number of underground banks and the amount of their outstanding loans.

But an innovative format of that kind of lending, called peer-to-peer lending (P2P), facilitated by China’s online banking system in recent years, had an outstanding loan balance of around 1.3 trillion yuan (US$188.7 billion) at the end of June, according to data quoted by People’s Daily.

Lufax looks to the future of peer-to-peer lending with blockchain technology

But that total is small compared to total funding in the Chinese financial system. Total social financing (TSF), stood at 1.18 trillion yuan in June alone and the outstanding amount of social financing was 183.3 trillion yuan at the end of June.

To replace the lending through informal channels that private firms have relied on, and move that financing on to a more regulated, transparent path, Beijing has urged state banks to grant more traditional loans to small companies.

To guide lending to small firms, authorities have been busy issuing “window guidance” instructions to banks, arranging meetings between executives of banks and private firms, and doling out tax breaks for banks that offer “microloans” to small firms.

On Wednesday the People’s Bank of China introduced a new policy tool – the targeted medium-term lending facility (TMLF) – to further spur lending to small and private firms.

In theory, state banks are heeding the call.

Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC), the country’s biggest state-controlled lender, said it had opened 230 centres nationwide this year to serve small business borrowers.

Interest rates on ICBC’s loans to small business averaged 4.64 per cent in August, below the average corporate lending rate of 5.97 per cent in the second quarter, it said.

Still, only a small minority of private firms are lucky enough to be able to take advantage of these loan terms.

George Yuan, a manager with an ICBC branch in eastern China’s Jiangsu province, said it remained “very, very difficult” for small private firms to get a bank loan.

Since late last year, ICBC headquarters has been issuing a “white list” of private companies, updated month to month, to its loan officers. The companies which make the list are supposed to enjoy a fast track service when applying for a loan.

“However, the internal big data-based selection of eligible companies only covers a tiny part of our clients, due to the strict criteria that are used,” said Yuan.

“Almost none of my clients are on the white list. Although I am the one who knows their business situation best, [the list] makes it extremely hard for me to get their loan requests approved [if they are not on it],” he said.

For a small company, a typical way to get a bank loan is by providing proof of taxes paid. Usually, if a company pays monthly tax at around 10,000 yuan, it will be able to get a loan worth no more than four times that amount, or around 40,000 yuan, Yuan said.

It is easier if a borrower can provide collateral for a loan. Property is the ideal collateral, allowing a loan for up to 70 per cent of its assessed value, he added.

Also, the loan application review process is wholly at the bank’s discretion, with no fixed timeline or criteria set, making the result highly unpredictable, Yuan said.

But even as the government pushes banks to lend more to small business, their access to credit has worsened due to the slowdown in the economy.

Some banks have tightened their loan review processes, opting to be more risk averse amid rising economic uncertainty.

The ICBC branch where Yuan works no longer accepts cross guarantees – a third party standing behind the loan application of another party – for granting loans to small companies.

This practice, which had been widespread in southeast China’s Jiangsu and Zhejiang provinces, led to too many bad loans in the past few years, Yuan said.

In one prominent case in late 2011, a wave of defaults was triggered in Jiangsu province when a cash flow crunch overwhelmed the loan guarantees that private iron and steel traders had provided for each other.

A bank loan officer gets a bonus if he gets a new client, Yuan said, noting this accounted for more than two-thirds of his own income.

But, because the value of the bonus is determined by the value of the loan, bankers have a much greater incentive to win over big state firms – which usually borrow more – rather than small private firms.

“From an effectiveness standpoint, it makes much more sense for a banker to explore new clients by tapping big state firms, rather than looking to small private companies,” Yuan said.

For each new corporate client, bankers need to go through their last three years’ of books, collect all kinds of paperwork related to the companies and their owners, verify the collateral and guarantees provided by the corporation.

It is a process that takes a full month, according to Yuan.

“Lending to SMEs is a difficult task for all countries around the world, no matter whether it’s a banking dominated economy, or a capital market dominated one,” said Aidan Yao, senior emerging Asia economist at AXA Investment Managers.

“When the economy goes up, and risk appetite rises, banks are more willing to lend to SMEs. But when [the economy] goes down, banks become risk averse, and stay cautious regarding lending to SMEs.

“Worldwide experiences show general [economic] easing is the most effective way to help SMEs, which are usually the last in the chain to get access to credit. But Beijing is staying away from this approach as its mission to cut debt is only half completed,” he said.

On Monday: Will China make good on its latest promise to give private firms more access in a market that favours the state sector?