How US trade war could leave Chinese private firms at risk of being ‘taxed to death’

- A rising tax burden is placing additional stress on private sector firms at a time when economic growth is slowing

- Despite the key economic role played by the private sector, Beijing has limited room for manoeuvre when it comes to cutting taxes

Chinese entrepreneur Lee Teng shut down his company last year, overwhelmed by his tax burden.

In mid 2016, China replaced its business tax with a value-added tax (VAT) across all industries. Even though the adjustment was intended to reduce the overall tax burden on companies, the effective tax rate on Teng’s Beijing-based firm rose by a percentage point.

This represented a considerable increase for a new-energy engineering company with 20 employees and annual revenues of 15 million yuan (US$2.2 million).

“I also needed to set aside as much as 40 per cent of my profits to pay social security tax premiums for my employees,” said Teng. “The collection process has become more and more rigorous in recent years [and] previous tax reduction methods no longer work.”

“Every cost is rising – staff salaries, rents, and utilities. The only thing that goes down is the value of orders. It is very hard to survive now,” he added. Teng is not alone in his plight. And this spells trouble for the Chinese economy.

Economic growth is already decelerating due to the effects of both the government’s programme to reduce debt and the trade war with the United States.

Given that private sector firms account for 60 per cent of growth, the government is counting on them to help stabilise the economy and so is scrambling to find solutions to their problems.

At the beginning of November, President Xi Jinping convened an unprecedented symposium of private entrepreneurs and told them that Beijing would help them.

The top priority, Xi told the gathering, was a substantial cut in their tax burden.

The Chinese private sector has long complained that it is being “taxed to death” and this burden was one of the top three concerns cited by mainland private firms in a survey conducted last year by the All-China Federation of Industry and Commerce.

But, so far, the government has not implemented specific steps to cut the tax burden. In fact, previous tax reforms increased the burden on private firms.

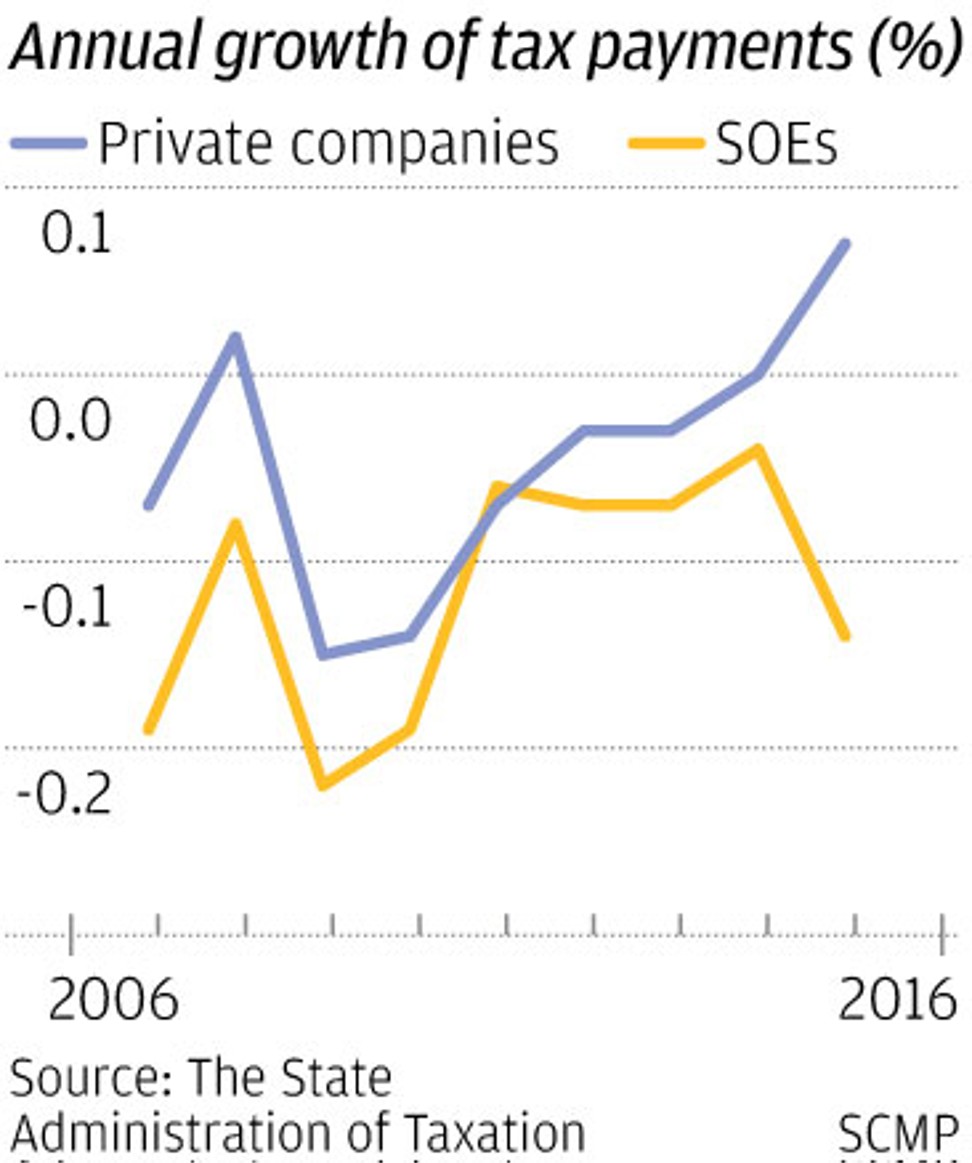

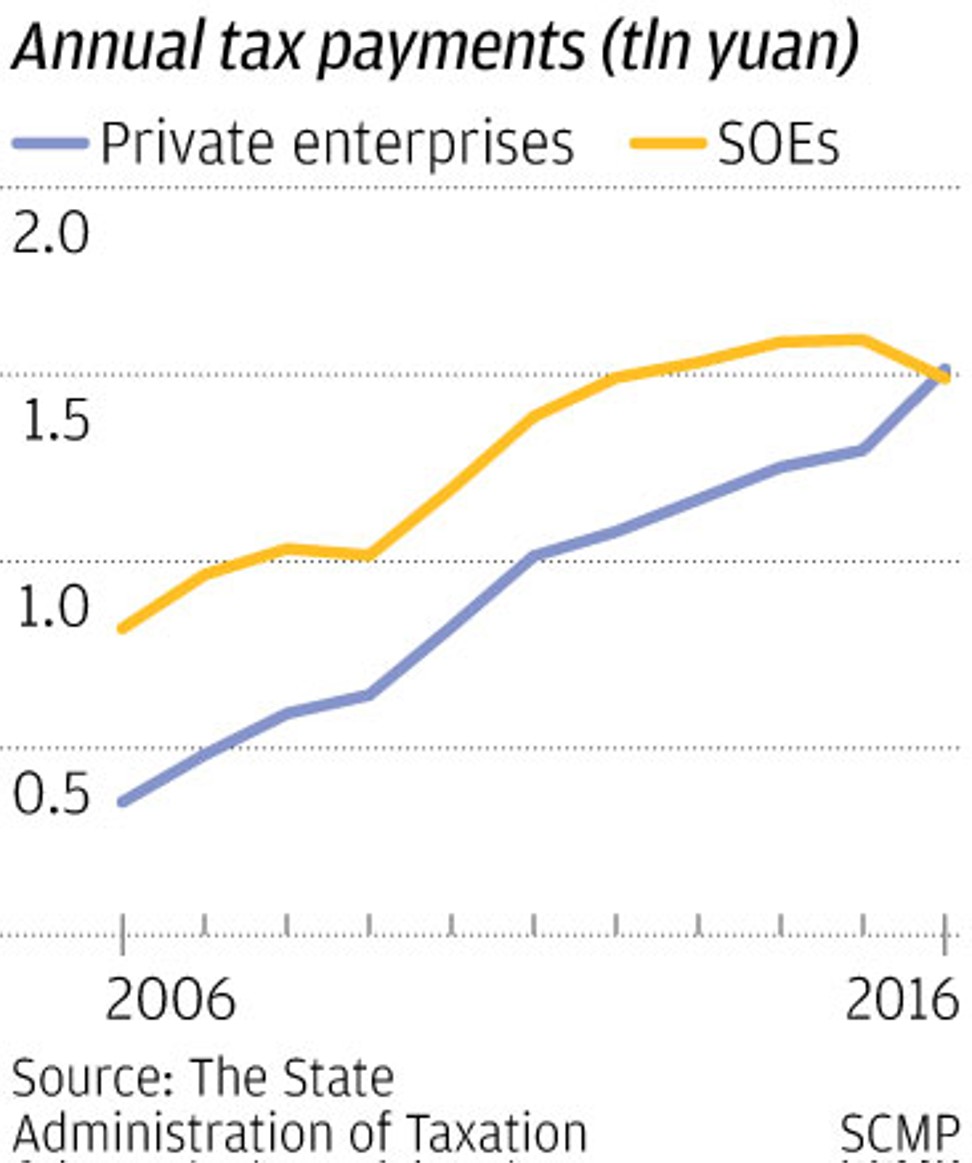

The total amount of taxes paid by state-owned enterprises (SOEs) dropped by 6.5 per cent following the switch to VAT in 2016, but the private sector’s tax burden jumped by 16.8 per cent, according to the data from the State Administration of Taxation.

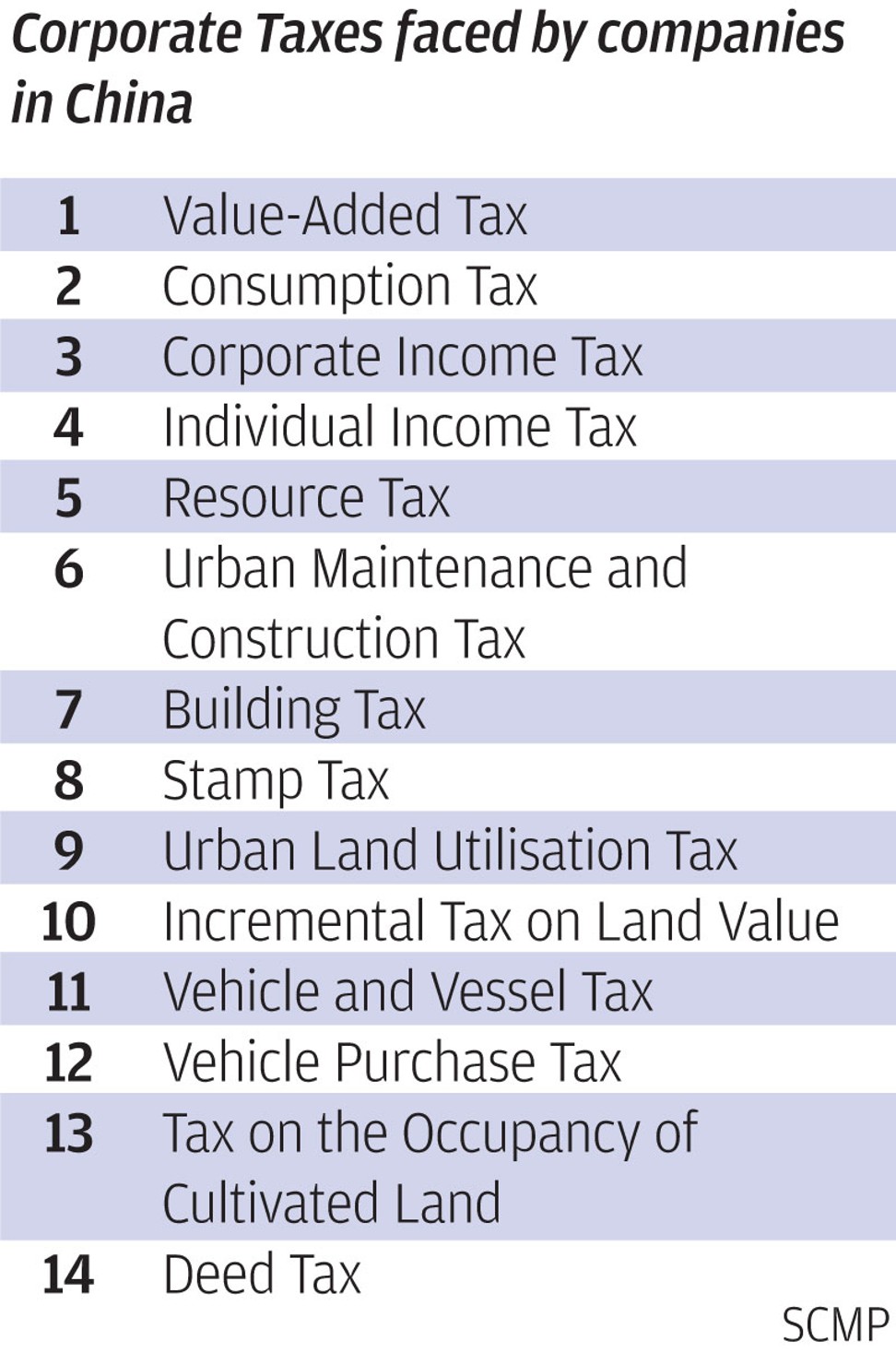

Private enterprises that year paid 1.5 trillion yuan (US$218 billion) in the form of 10 different corporate taxes – in total they paid 24 billion yuan (US$3.4 billion) more than SOEs.

Moreover, these figures do not include payments for five social taxes – including employee pensions, and health care and housing levies.

Since these taxes are based on the number of workers a firm employs, and given that private sector firms employ 80 per cent of urban workers, social tax payments push the total burden on the private sector well above that on the state sector.

Private firms used to pay social taxes based on deals with local tax authorities that allowed them to calculate their bills at the minimum wage rate, a legal expedient that ensured their continued profitability.

But they are now braced for a major increase in their tax bills when the central government takes charge of collecting contributions, a switch that will mean the levy will be based on actual wage rates.

In September Premier Li Keqiang tried to calm private sector fears by asking local authorities not to switch to the new levy immediately, but the change is still due to come into force in the new year.

“That [change] will increase the tax burden on Chinese corporates by 2 trillion yuan [US$291 billion] in 2019, about 20 per cent of the total profits generated by Chinese companies last year,” Hu Yifan, chief China economist at UBS Wealth Management, told the South China Morning Post.

Following Xi’s comments last month, Vice-Premier Liu He, his key economic adviser, vowed to enact a major tax cut for private enterprises.

But Hu from UBS warned that actually doing so would not be easy, since the central government’s large, inflexible spending commitments limit Beijing’s room for manoeuvre.

“China needs to pay for a large number of civil servants, spend on social welfare programmes and on infrastructure projects,” Hu said.

“Unless there is a structural overhaul of fiscal expenditures, such as handing over some infrastructure projects to private enterprises or reducing the number of civil servants, it will be hard to cut taxes [much],” Hu said

“Even if they really do cut taxes, the size [of the cut] matters. So far, China’s tax cuts have not been as large as the market expected.”

In May, China reduced the valued added tax rate, the largest levy that Chinese companies pay, by just one percentage point, well below what the market and the private sector had hoped for.

In this environment, Channey Zhan – who runs a hi-tech ceramic glassware manufacturer in the southern province of Guangdong – might be one of the lucky ones.

Her company has been able to secure certification as a hi-tech enterprise, which ensures a preferential corporate income tax rate, and the provincial authorities have also offered her access to research and development projects. But these favours came at a price.

“We spent a lot on guanxi [favours given to build influential relationships] during the process. The total amount is difficult to calculate,” Zhan said.

“The government won’t proactively tell you to apply for projects, we have to seek those out by ourselves and deal with the red tape.”

She joked: “I might find my company was losing money if I calculated these implicit costs, so I’d better pretend that nothing happened.”

“Good resources always flow to SOEs and foreign enterprises first, so we can only scramble for what remains of the cake and have to cope with so many documents, procedures, and approvals.”

Paying the cost of maintaining good guanxi is also crucial for Ray Quan, the executive director of an automotive materials firm in Changzhou in the eastern province of Jiangsu, because he needs to ensure that his main client pays on time.

“Our client is an SOE, we basically have no bargaining power,” he explained.

Although the State Council, China’s cabinet, has started a special research project to document the extent of government and SOE payment arrears to private sector firms, according to a document seen by the Post, there is currently no data on how much is owed by state entities.

But Quan doubted that researchers would be able to uncover the true extent of the problem.

“You can report arrears, but then they may no longer do business with you,” he said. “As long as the [SOE] business is there, we just grin and bear it.”

Both Zhan and Quan are also having to deal with the year-on-year increase in labour costs.

Zhan said she has had to increase her employees’ salaries by around 3 per cent each year just to offset the impact of inflation.

Quan added that to survive in the current competitive environment “we need to pay more money to retain high-skilled talent”.

The latest survey by China’s federation of industry and commerce showed that rising labour costs were the top worry for private enterprises for the fourth year in a row.

Labour and other costs will continue to rise no matter how the Chinese economy is performing, according to last month’s business conditions index compiled by Cheung Kong Graduate School of Business in Beijing.

Zhan said she was now having to rejig her production lines to tide her over the difficulties resulting from slowing growth.

Quan was even more cautious, saying his business was unlikely to survive an economic downturn.

“Now, I am thinking more about making my personal life stable,” he said.