First woman priest in the Anglican Church, in 1944, Hongkonger Florence Li ministered to wartime refugees in Macau

- When the Church of England began ordaining women priests in 1994, few people appreciated that the first woman had been ordained 50 years earlier in Hong Kong

- Li’s ordination in 1944 was hugely controversial, and she soon resigned. In 1971, Hong Kong Anglicans became the first to permit the ordination of women priests

The name Florence Li Tim-oi may not ring a bell with many people today, but the Hongkonger was a women’s rights pioneer and a stalwart of the Anglican Church known for her tireless work with refugees during the second world war.

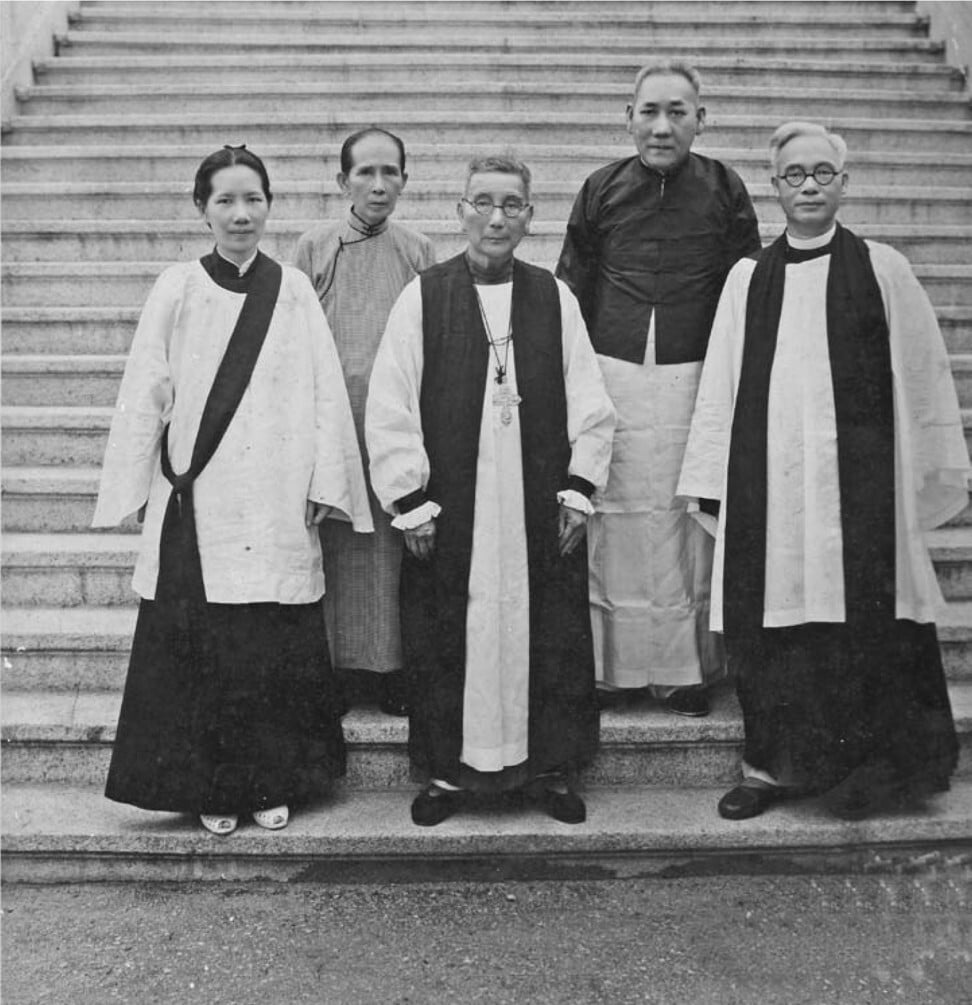

Li was the first woman ordained a priest in the Anglican Communion, the third largest Christian communion after the Catholic Church and Eastern Orthodox Church. Her ordination took place on January 25, 1944, in Zhaoqing in Guangdong province, southern China, and was presided over by Ronald Hall, an Anglican bishop of Hong Kong.

The move was hugely controversial. Angela Wong Wai-ching, a Hong Kong scholar of Asian feminist theology, says in the 1930s the Anglican Church supported women deacons – who assist bishops and priests in public worship – but not ordained priests.

“Women were not considered proper representatives of Jesus Christ,” says Wong, a faculty member at Chinese University of Hong Kong. “Other reasons were the biological ‘deficiency’ of women, ranging from menstruation [to] pregnancy and their emotional state.”

Hall — himself not an advocate of the ordination of women — made the unprecedented move for practical reasons: the Japanese occupation of Hong Kong and of parts of China during the second world war meant Anglican priests could not get to Macau, the then Portuguese territory on the opposite side of the Pearl River Delta to Hong Kong, to carry out their work.

Li, who was made a deacon in 1941, was working in Macau (mostly helping war refugees), so Hall thought it would be pragmatic for her to carry out the priestly duties, specifically administering the holy communion.

“There was a great demand for ministers during wartime, and Li was the only one available to take up the responsibility to lead the Anglican Church in Macau at the time,” says Wong.“She did not only take the responsibility with courage but also charisma. She took care of the refugees and brought the small church in Macau up exceedingly well.”

In 1946, soon after war ended, Li surrendered her priest’s licence. She wanted to defuse any controversy and spare Hall further fallout from her controversial appointment.

“Following the formal decision to reject the ordination of Li at the Lambeth Conference [a gathering of bishops] after the war, Hall was given the choice of revoking the decision or resignation. Instead, Li submitted her resignation,” Wong says.

In 1971, Hong Kong reached another milestone when it became the first Anglican province to officially permit the ordination of women to the priesthood. Jane Hwang and Joyce M. Bennett were ordained by Gilbert Baker, a bishop of Hong Kong and Macau, on November 28, and the move added more fuel to the debate over whether women should become ordained priests.

“The same arguments about the emotional state and the biological ‘deficiency’ still prevailed,” says Wong. “Reasons are theological: that Jesus was a man; social, that women were not trusted to be leaders to make the right decisions; and political, that most sitting in the decision-making bodies were men.”

“There are more nuanced analyses to be given,” she adds. “But the church always has the privilege to refer to the Bible and the theological traditions as something that stand above any change of the times, when the presiding personnel do not want any change.”

When the Church of England began ordaining women priests in March 1994, few people appreciated that the first woman had been ordained 50 years earlier in Hong Kong.

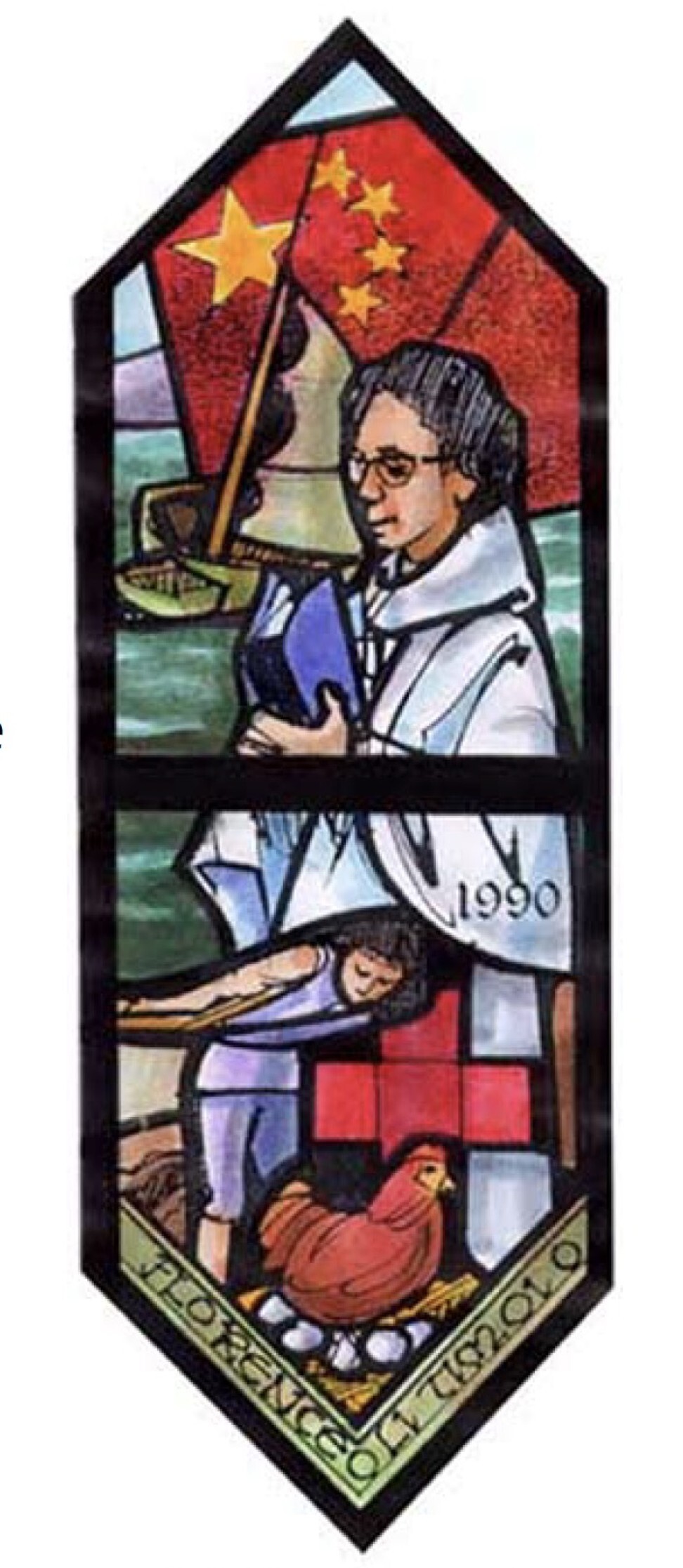

“Florence Li was a pioneer in women leadership in the patriarchal church of her time, and she remains the voice of conscience for those who are willing to hear,” says Wong.

More about Li and her extraordinary achievement

According to the Li Tim-Oi Foundation, a charity set up in 1994 in her memory, Li was born on May 5, 1907, in the Hong Kong fishing village of Aberdeen. With five brothers and two sisters, there was little money for her schooling (she started late, at 21, and was 27 when she left school).

As a student, she joined an Anglican church, and at her baptism took the Christian name Florence – after British nurse social reformer Florence Nightingale, the founder of modern nursing. While at the Union Theological College in Canton, now Guangzhou, she led a team of students rescuing the casualties of Japanese carpet bombing, and narrowly escaped being a casualty herself.

From 1958 to 1974, under Maoist persecution, churches in China were closed. The Li Tim-Oi Foundation website says Li was forced by Red Guards to cut up her vestments with scissors and was sent for political “re-education”.

During China’s Cultural Revolution, Li lived in obscurity and hardship, working on farms and in factories, in what she says was a very dark period of her life. She even contemplated suicide.

When the Bamboo Curtain was lifted, Li was allowed to leave China. In 1983, she moved to Canada, where she was appointed an honorary assistant at St John’s Chinese congregation and St Matthew’s parish in Toronto. The Anglican Church of Canada had by this time approved the ordination of women to the priesthood.

In 1984 – the 40th anniversary of her ordination – Li was reinstated as a priest. This event was celebrated not only in Canada but at Westminster Abbey in London and in Sheffield in England, even though the Church of England had not yet approved the ordination of women.

She served at Toronto’s Anglican Cathedral for several years before her death on February 26, 1992, aged 84. She is buried in Toronto.