He couldn’t tell they were Chinese: dying Chinatown of Havana, Cuba, documented in US-based photographer’s exhibition

- The first Chinese arrived in Cuba in the 1850s, but finding their mixed-race descendants on the streets of Havana today wasn’t easy for Lau Pok-chi

- Among the subjects of the Hong Kong-born photographer’s exhibition in Shenzhen is a 90-year-old woman believed to be the last Cuban diva of Chinese opera

Caridad Amaran is believed to be the last Cuban diva of Chinese opera. She learned the traditional art form from her Chinese stepfather, who taught her how to read the language.

At 90 years old, Amaran – who has been performing since childhood – is still an active singer, and she is one of the extraordinary subjects featured in photographer Lau Pok-chi’s latest solo exhibition, “Chinese Diaspora”.

Lau, Hong Kong-born and based in the US state of Kansas, says he stumbled upon the talented singer by accident. When they met, he found her scrubbing oil off a Chinese printing press with a kerosene-soaked toothbrush. “I couldn’t believe this Cuban woman could recognise these Chinese [characters] and put them in order,” Lau recalls.

The exhibition, which runs until August 30 at the Yuezhong Museum of Historical Images in Shenzhen, over the border from Hong Kong in southern China, charts the decay of Havana’s Chinatown, the country’s once-thriving Chinese culture and community, and its mostly mixed-raced descendants.

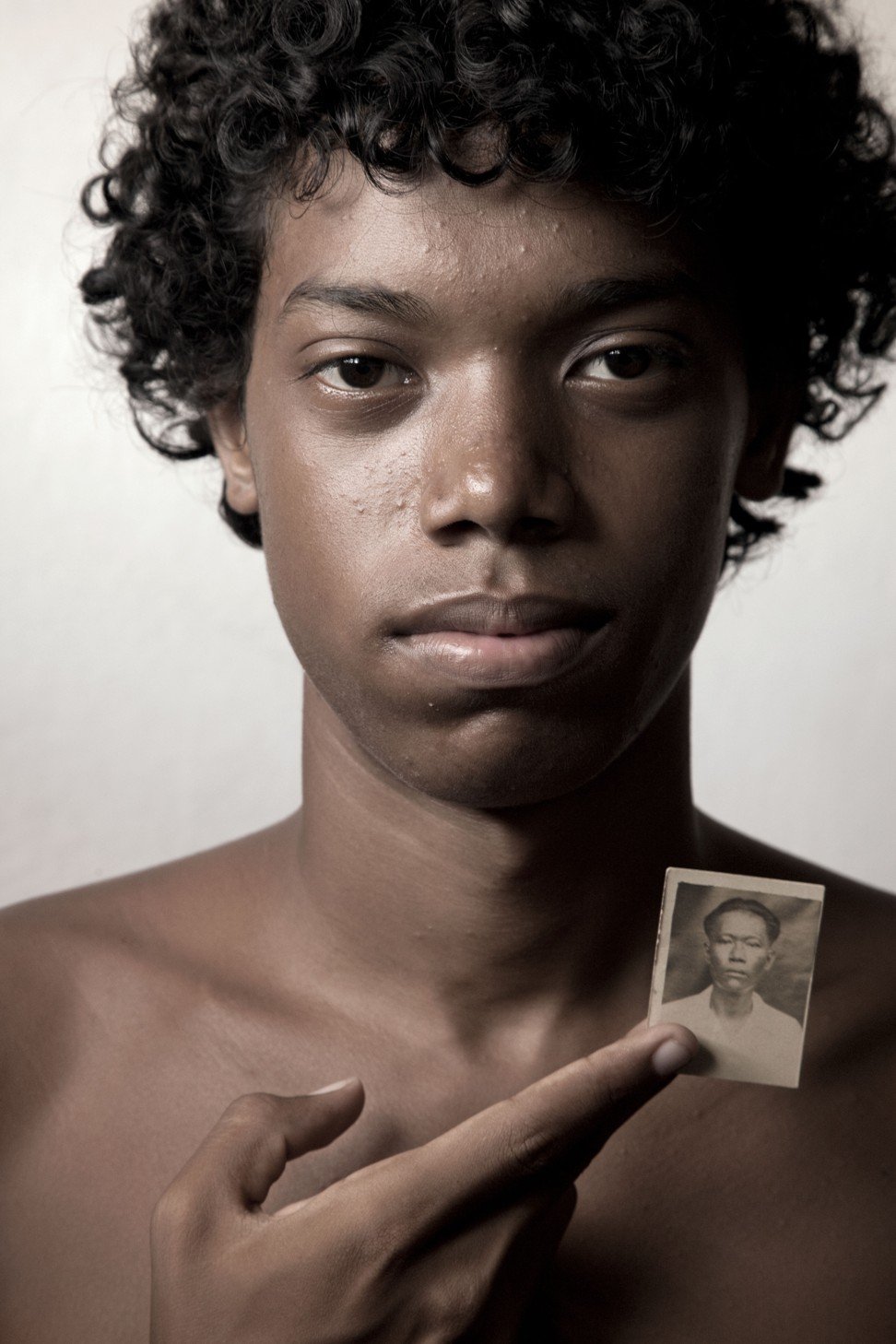

Another portrait on show is that of the young Yamil Antonio Fong, who is seen holding a picture of his Chinese grandfather. “I document the living conditions of the second, third, fourth generations … but my work is not out there to shock, it’s more about the quiet observations,” says Lau.

His images of the younger generations with pictures of their Chinese ancestors are poignant, and are a reflection of a long history between the two countries.

In the 1850s, the first wave of Chinese people arrived on the island. They were slaves and, later, farm workers that worked on the country’s sugar cane plantations. The immigrant population grew, peaking at around 40,000 in the 1880s; that was also the high point of their influence and of Havana’s Chinatown.

Lau, who is a professor emeritus at the University of Kansas, has been documenting the movement of people from China to other parts of the world, as well as their mixed-race descendants and stereotypes. He is currently on a three-month road trip in Mexico, where he will visit Mexican Chinese communities.

Lau found that Chinese Cubans often lived in more poverty than Chinese people elsewhere. “Many of Havana’s older Chinese retirees still have to go to the Family Association to get their free meals, packing any leftovers for their families at home,” he adds.

Relations between the two countries have been further strengthened by Cuba’s sympathetic response to the coronavirus pandemic, with China’s foreign ministry reporting on a phone call between President Xi Jinping’s and Cuban President Miguel Diaz-Canel.

Though there might now be little demand for Chinese arts or culture in Cuba, Amaran’s talents have found an audience outside the country. Lau has taken the diva twice to Hong Kong to perform – most recently for last year’s Hong Kong Arts Festival – and once in 2011 to China.

There, he recalls: “Caridad, with no Chinese blood in her, sang the first song she learned from her Chinese stepfather in front of the landmark of his ancestral village. She even remembered the name of the village. It was so touching.”