Review | Bruce Lee’s daughter Shannon turns her martial arts icon father’s ideas into a self-help guide in Be Water, My Friend

- Shannon Lee’s book takes aphorisms and observations from her father’s handwritten notebooks and broadens them out to address modern living

- It is very good when it talks about the philosophy behind Lee’s martial arts system jeet kune do, but less so when it tries to apply it to modern life

Be Water, My Friend: The Teachings of Bruce Lee, by Shannon Lee, pub. Barnes & Noble. 3/5 stars

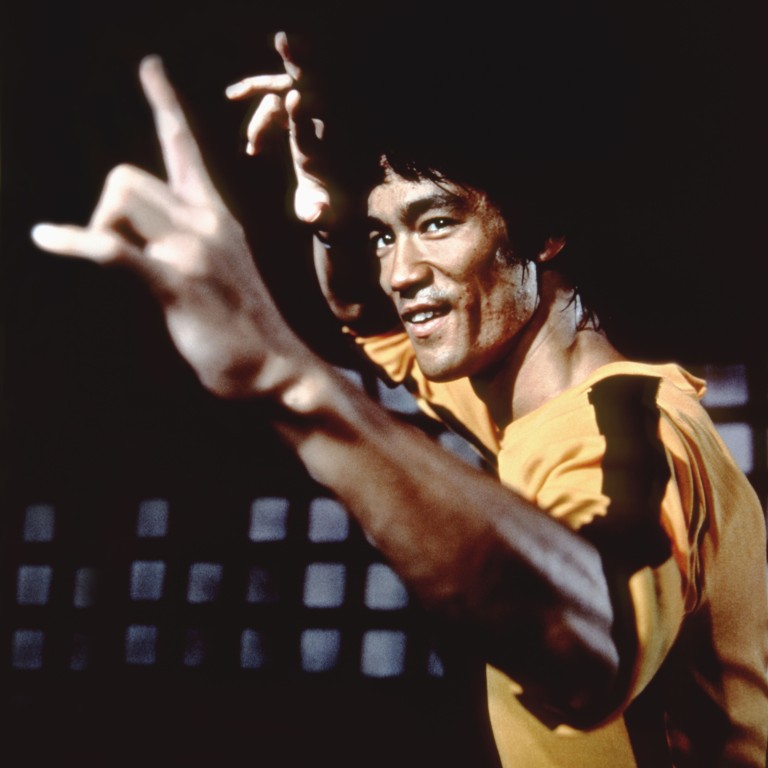

Over the last few years there has been a move to elevate Bruce Lee from martial arts icon to philosopher. That is probably an exaggeration, although Lee was certainly a thoughtful and well-read young man – he possessed a library of around 2,500 books, including philosophical works by Thomas Aquinas, David Hume and René Descartes.

Be Water, My Friend: The Teachings of Bruce Lee is a tenderly written book by his daughter Shannon Lee, who is also the president of the Bruce Lee Foundation, that takes sections from Lee’s handwritten notebooks – mainly aphorisms and observations – and broadens them out into a self-help guide for modern living.

The book is very good when it talks about the philosophy behind Lee’s martial arts system jeet kune do – his thoughts on the rigidity of fighting styles mean that he could never describe his system as a “style” – but less successful when it tries to apply his ideas to everyday life.

Lee’s own approach emphasised flexibility, arguing that a fighter should use whatever techniques necessary to win a fight, and should not be afraid of borrowing from other styles. Lee’s jeet kune do made use of elements of wing chun, tai chi (which emphasises natural balance and flexibility) and Western boxing (which provides raw power and fast footwork), among other styles and disciplines.

One of the best parts of Shannon’s book is when she details the fight which led Lee to realise that a traditional approach did not equip a fighter to deal with a real-world situation. Lee and his opponent had agreed to dispense with the traditional rules, but he was not prepared for the way the fight developed, Shannon writes.

Hong Kong martial arts cinema: everything you need to know

“First of all, he’d had to chase the man around the room – something you’d not normally do in a fight – and he became winded. Secondly, he had to attack someone from the rear who was running away – also not something that you practice in martial arts,” she writes.

As the book points out, Lee’s ideas originated from traditional sources. Taoism, which emphasises flow – translated into fluidity for martial arts practice – and Zen Buddhism, which in martial arts terms is used to emphasise reacting to the moment rather than trying to follow a predefined fight plan, are central to his ideas. A detailed analysis of this is available in the book Tao of Jeet Kune Do.

More radical was the way that Lee negated Confucianism, which is central to Southern-style martial arts. His rejection of tradition, along with the martial arts hierarchy that it maintained, was an attack on the Confucian ideas that had regulated the practice of martial arts for at least a couple of centuries.

Lee, of course, was not the first to bring philosophical ideas to Chinese martial arts – the practice is built on philosophical ideas.

When the monks in the Shaolin Monastery began developing martial arts in the early seventh century to defend themselves from bandits, they needed a philosophical underpinning that justified their use, as Buddhism prohibits violence. From then on, philosophy and Chinese martial arts were intertwined.

Shannon’s book does a good job of representing Lee’s updating of such ideas, but falters when it tries to use them as the basis for a self-help guide.