Father of modern Chinese ink painting Liu Kuo-sung says there’s still much he can do for the art as he nears 90

- Liu Kuo-sung explains that while he is satisfied with all that he has achieved, he still wants to help young, talented but unknown artists gain recognition

- He is happy to see Chinese ink art gaining in popularity in the West: “In the past it was the Chinese who learned Western painting. Now it’s the reverse”

Spry and sprightly, Taiwanese artist Liu Kuo-sung will turn 90 in April 2022 and even though his extensive travels in nature, which provide the inspiration for many of his abstract works, have been suspended since the Covid-19 pandemic broke out, he is still drawing as often as he can.

When international borders reopen, he says he wants to go to Shanghai to resume his teaching at the Shanghai Institute of Visual Arts’ Academy of Contemporary Ink Art, of which he is the head.

“My students are illustrious figures in the arts industry,” he says. “Some are university fine arts professors. Some are the heads of art museums.”

Known as the father of modern Chinese ink painting and a pioneer of Chinese modern art, Liu has a litany of achievements to look back on.

In 2013, the Shandong Museum in eastern China opened the Liu Kuo-sung Modern Ink Art Gallery to display a permanent collection of around 100 of his works. His painting Scenery of Hong Kong sold for HK$16.8 million at a Christie’s auction in Hong Kong in 2014. In 2016, he was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, making him the first Taiwanese recipient of the honour.

In an interview from his home in Taiwan, Liu says that while he is satisfied with what he has achieved, there is still much he can do for the advancement of Chinese ink art.

Hong Kong’s long-awaited M+ museum announces early bird ticket details

“I am in talks with art museums which want to do a retrospective of my body of work when I reach 90,” says Liu, who is also a visiting professor at the National Taiwan Normal University. “I want to help young, talented and hard-working but unknown artists by recommending them to society.”

The biennial Liu Kuo-sung Ink Art Award, set up in 2019 by Liu and Hong Kong non-profit The Ink Society to recognise and highlight young emerging ink artists, awards HK$100,000 (US$12,850) to a winner selected from 15 candidates nominated by arts experts. The 2021 winner, Bian Kai, is a lecturer in ink art at the Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing.

Born in China’s Anhui province to a soldier and a housewife, Liu had no early training in art. Japanese forces killed his father when he was only one year old and, like many mainland Chinese families during World War II, Liu’s was constantly running for their lives. He did not receive formal education until he was in his teens.

At the age of 14, Liu was given a place at a school for orphans of revolutionary soldiers funded by the Kuomintang political party. To pursue his studies, he later left with his school for Taiwan. His mother remained in communist China.

Liu loved art as a child and would spend hours browsing a Chinese painting shop after school every day.

“I was too poor to afford any painting materials. The shop owner gave me some paper and paint brushes for self-learning. I imitated old paintings until my first year at university, when my arts teacher told me art should originate from life. I stopped mimicry and began sketching what I saw in real life,” Liu says.

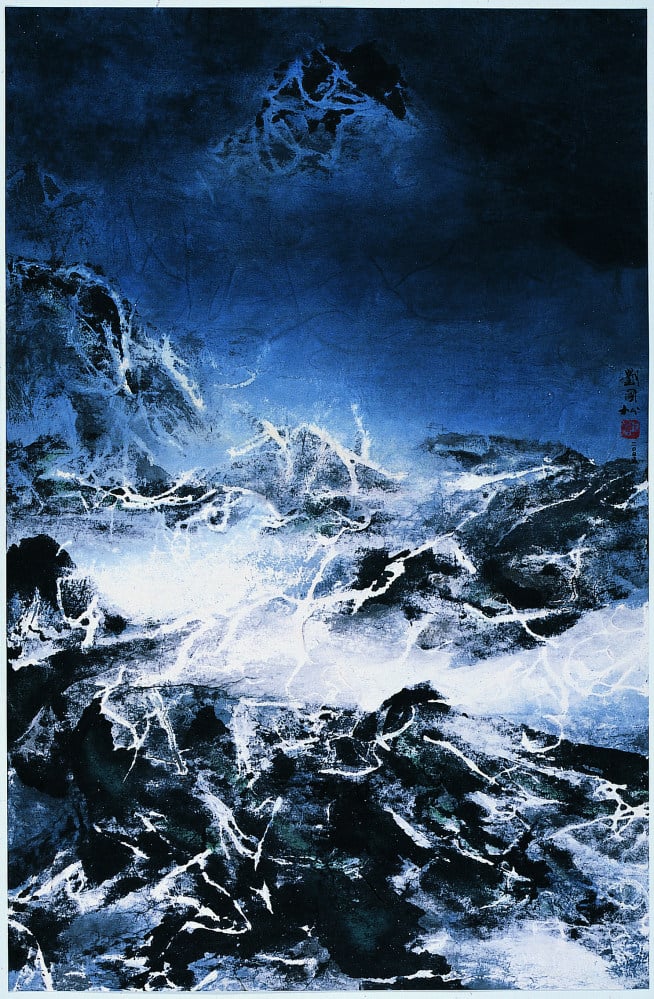

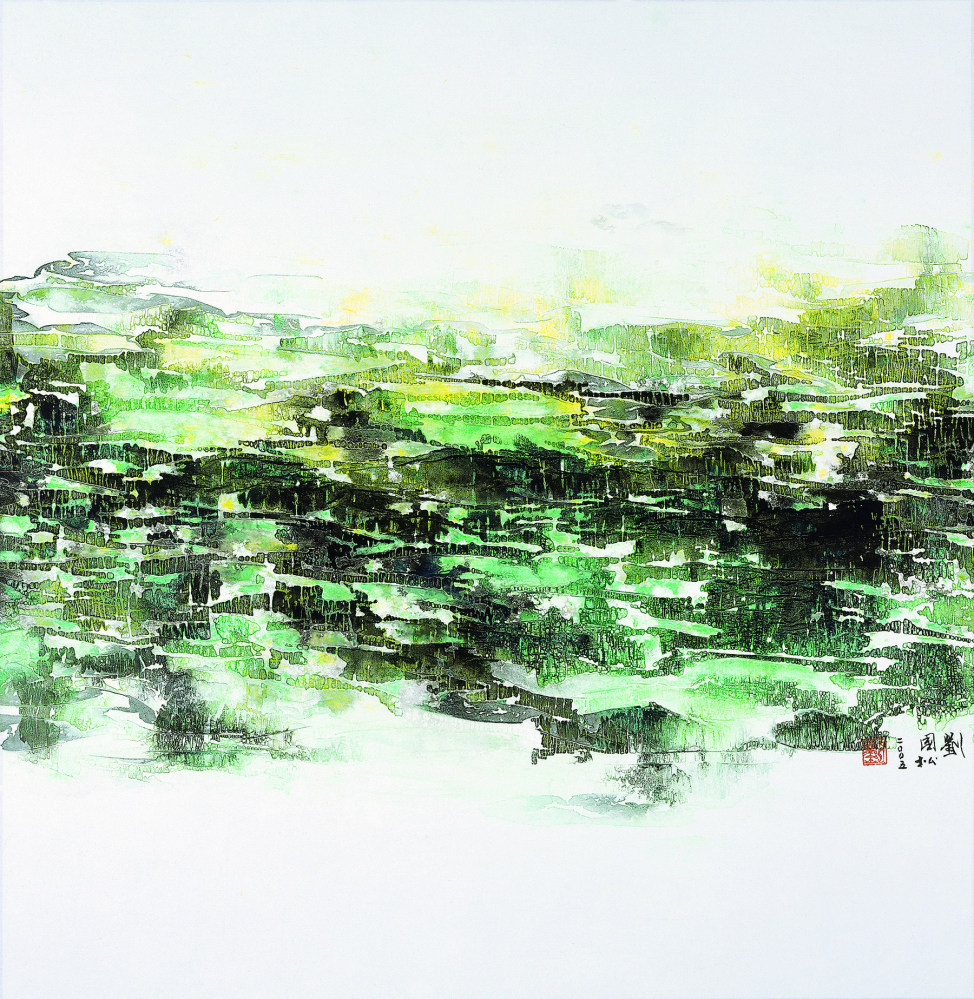

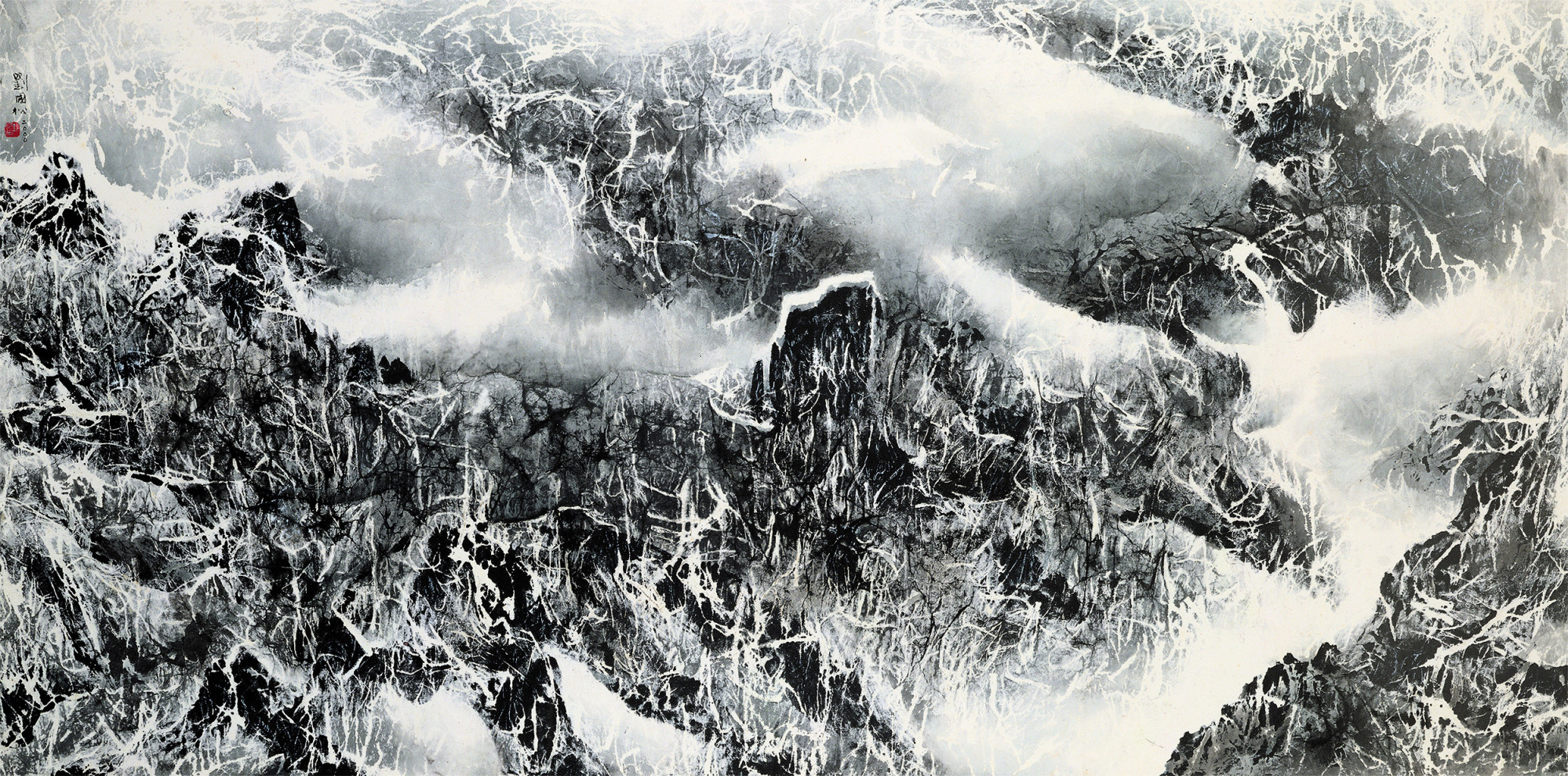

In the 1950s, he began to develop a form of Chinese art that used new techniques and materials. He experimented with using coloured Chinese ink and acrylic on paper, not canvas. He applied multiple techniques such as reverse print, collage and folding.

By 1963, Liu had invented a new type of material using thick-grained cotton paper to add texture to his art. Called “Liu Kuo-sung paper”, it inspired subsequent contemporary artists to make more sculptural paintings.

In the early 1970s he was invited to teach in the Chinese University of Hong Kong’s department of fine arts, which he did from 1971 to 1992.

The Palace Museum has acknowledged my status in Chinese art history. My art has come full circle to reach home. My life has not been wasted

When the Research Institute of Traditional Chinese Painting under the Chinese Ministry of Culture was set up in 1981, Liu was invited to exhibit his art. He travelled around China and held shows in 18 cities.

The overwhelming response he received from the shows led to him being blacklisted in Taiwan, and it wasn’t until 1989 that he was invited back for a solo exhibition.

In 2000, he lost the hearing in his left ear after a trip to Mount Everest. “Overwhelmed by the fast-changing weather and scenery, I spent too long there,” he says. “I could not paint for half a year due to treatment. Though the treatment failed in the end, I produced a lot of work on the mountains.”

In 2007, Liu reached the pinnacle of his career when the Palace Museum in Beijing held a show of his works.

“I first launched my modernisation of Chinese painting in Taiwan, which later spread to Hong Kong and Southeast Asia, Korea and Japan. It reached mainland China in the end. The Palace Museum has acknowledged my status in Chinese art history,” he says. “My art has come full circle to reach home. My life has not been wasted.”

Liu is happy to see Chinese ink art gaining in popularity in the West.

“The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York held a show called ‘Ink Art’ in 2013. The Los Angeles County Museum of Art presented ‘Ink Dreams: Selections from the Fondation INK Collection’ in July. The show features works by Chinese and Western artists,” Liu says.

“In the past it was the Chinese who learned Western painting. Now it’s the reverse.”