Five Star Wars myths, from it being a template for blockbuster movies to only young white men watching the films

- Star Wars films have been steeped in folklore, such as the idea that the sound of lightsabres came from the hum of a projector, so what is true and what isn’t?

- With The Rise of Skywalker storming the box office, there’s reason to delve into five myths that have surrounded the famous franchise since it first began

Star Wars is a kind of fable, but it has also spawned a class of fables about its creation.

From the idea that the sound of lightsabres came from the hum of a projector to the claim that George Lucas found inspiration for Chewbacca in his Alaskan malamute, there has been no shortage of tales connected to the film.

Those stories are difficult to substantiate – or to disprove, for that matter.

But as The Rise of Skywalker makes its own ascent at the box office, it’s worth interrogating some of the other stories that Lucas, Lucasfilm and Disney have promoted to burnish their product.

1. Star Wars provided the blueprint for blockbusters

The original Star Wars seems to have been engineered to be the perfect blockbuster. Retrospective accounts present the 1977 film as an immediate game changer that served, as Vox puts it, as an instant “blueprint” for studio production. An article on Medium, likewise, holds that with the first Star Wars film, “the blueprint for the Summer Blockbuster had arrived”.

While it is true that Star Wars was an immediate box office sensation, surprised studio executives spent the next 10 years scrambling to formulate what made it so, incurring expensive bombs like The Black Hole, Dune and Tron along the way. That may have been because A New Hope does not look much like what blockbusters would become. Remember, for example, that the first 20 minutes is primarily occupied not by human actors but by things called droids.

It also did not help that Lucas was an idiosyncratic filmmaker. Although the young director’s 1973 movie, American Graffiti, had been a surprise smash hit, he had a reputation as one of the artier and more esoteric of the young film school graduates, based largely on his 1971 THX-1138 and his abstract student films, which had made the festival rounds.

Lucas claimed that he wanted Star Wars to demonstrate that he could be a crowd-pleasing director, but the movie was explicitly budgeted and marketed to be a modest moneymaker for the niche science fiction and juvenile audience.

2. Lucas drew primarily on myths to create Star Wars

In a 1999 interview with Bill Moyers, Lucas stated: “When I did Star Wars I consciously set about to recreate myths and the classic mythological motifs.” He said he’d learned a great deal from Hero With a Thousand Faces author Joseph Campbell, whom he called a mentor. As The Guardian’s Jonathan Jones sums it up, the original film was “a tale, a legend, a myth … an epic yarn, pure and simple”.

In practice, Lucas’s evocation of Campbell – and his Jungian theories of storytelling – is most likely a post-dated attempt to add intellectual heft to the project. Early biographers of Lucas do not mention Campbell, and the two men did not even meet much before 1987, when Campbell died, by which point Lucas had completed the original trilogy.

By contrast, in interviews from the 1970s, Lucas said he disliked the “storyteller” label. He called himself a “pure” filmmaker concerned with images, and complained bitterly about how much he hated the act of writing.

While pitching his original treatment for the film in 1974, Lucas eschewed references to classical mythology, instead calling it “2001 meets James Bond [in] outer space”. In the 1970s, he most frequently cited pulp adventure stories (such as the Flash Gordon and Buck Rogers serials) and Edgar Rice Burroughs’ John Carter of Mars novels.

He said then that his research on myths and fairy tales was geared toward finding the right structure for his Star Wars stories, helping him to string together the set-piece elements such as space battles and planetary vistas.

3. Star Wars ended a mature, arty ‘New Hollywood’ cinema

For many critics and scholars, Star Wars helped introduce the effects-heavy, overproduced, expensive, juvenile Hollywood blockbuster that soon pushed out more-mature films by “New Hollywood” American auteurs such as Hal Ashby, Robert Altman and Sidney Lumet.

Peter Biskind saw Star Wars as the “mirror opposite” of New Hollywood. As he put it: “When all was said and done, Lucas and Spielberg returned the 70s audience, grown sophisticated on a diet of European and New Hollywood films, to the simplicities of the pre-60s Golden Age of movies.”

Building on this narrative, critic Mark Harris described Top Gun as a logical outgrowth of Star Wars blockbusterism, writing that it heralded an end to the days when “adults were treated as adults rather than as overgrown children hell-bent on enshrining their own arrested development”.

Lucas and Spielberg returned the 70s audience to the simplicities of the pre-60s Golden Age of movies

From another perspective, though, Star Wars was New Hollywood in another form. Lucas, Steven Spielberg and others considered themselves to be extensions of New Hollywood’s director-driven, auteurist tradition.

Lucas did not see technical and extensive effects as contradicting the writerly model of auteurism, but as a more up-to-date version for a more visually driven age. Instead of complicated plots and snappy dialogue, Star Wars featured complex visual dynamism and intricate editing patterns.

What Biskind and others did not recognise is that the subject matter and script of Star Wars may have been purposefully naive, but its visual aesthetics were as sophisticated, and perhaps more daring, than anything New Hollywood produced.

4. Star Wars fans are usually young white men

For decades, many have assumed that Star Wars’ audience looks a lot like Luke in A New Hope: young, white and male. Cosmopolitan magazine’s recent “Millennial Woman’s Guide to Star Wars” bolsters that stereotype.

Fan rhetoric objecting to the greater visibility of women and people of colour as characters in the franchise has got so ugly that Russian troll farms have identified the topic as a wedge issue to further divide American political opinion. One recent study suggested that more than 50 per cent of accounts tweeting negative opinions on The Last Jedi were “likely politically motivated or not even human”.

To be fair, Star Wars merchandising was and still is primarily aimed at boys, as the #WheresRey and #WheresRose hashtags – which call attention to the lack of female action figures – demonstrate. But that very frustration is a reminder that the franchise’s fan base is more diverse than some assume. In fact, it’s also female, queer, black and Latinx, in substantial numbers. And that diversity isn’t a recent phenomenon.

Going back to the early 1980s, official Star Wars fandom publications such as Bantha Tracks show images of diverse fans meeting the stars. And in popular science fiction magazines such as Cinefantastique, and fan-created magazines and slash fiction up to the present day, fans of all backgrounds both revel in the imaginative universe and critique it by pointing out its omissions, even as they strive to expand its scope.

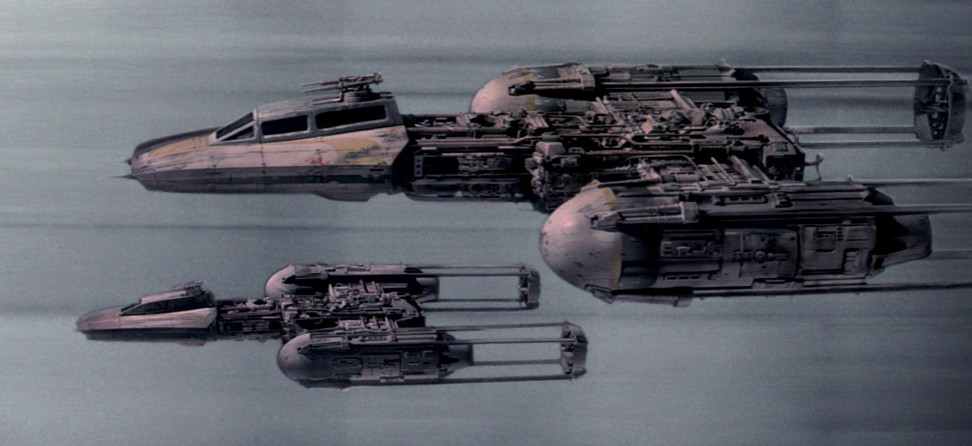

5. A team of young rebels did all the effects for Star Wars

The now-famed effects company Industrial Light and Magic (ILM) was assembled in 1975 to make the first Star Wars. As Lucas put it later: “We had about 45 people working for us. The average age was 25 or 26.”

Nearly all popular histories of ILM tell the same stories of the young, fun-loving, rule-breaking magicians, upstarts attacking a more staid cinematic world. Lucasfilm has been especially attached to this idea, which reinforces Lucas’s image as a defiant visionary. But this story co-opts a great deal of the equally inspired effects labour performed by the many non-ILM freelancers on the original trilogy.

Much of the work, including iconic elements such as the lightsabres (Van Der Veer Photo Effects), the aura around deceased Jedi (Lookout Mountain Films) and the blueprints of the Death Star (Larry Cuba), was farmed out to contractors.

These outside vendors brought a great deal of creativity and innovation to the movies. One of the many experimental filmmakers who freelanced on the original trilogy, Lookout Mountain’s Pat O’Neill, told me that he created the glow around Ben Kenobi in Return of the Jedi by joining together elements of sunlight reflecting off the Pacific Ocean.

Yes, the original ILM team created innovative and influential work on Star Wars, but the production also benefited from the outside work of experimental filmmakers, early digital pioneers and even old-school Hollywood effects artists.