Unequal opportunities: why are top women executives still expected to choose between work and family?

- Top Hong Kong executive Lily Cheng talks about gender inequality persisting in pay, career expectations and work-life balance

- She cites legacy stereotypes, personal preference and cultural acceptance as hurdles to achieving equality between the sexes in the workplace

There is a popular internet meme that rings true for many working women: we expect women to work like they don’t have children and to raise children as if they don’t work.

In recent months, a slew of women in power have resigned: New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern, First Minister of Scotland Nicola Sturgeon and YouTube CEO Susan Wojcicki. All three have cited to some extent the wish to spend time with their family and concentrate on their personal lives.

Taking these reasons at face value, one is left with the question, why are women still forced to choose between the two? Why aren’t more men retreating from positions of power for family? What more work needs to be done for gender equality in the workplace?

“There are many reasons, but one of them is that our corporate world makes it hard to be in the C-suite and be able to be a co-parent and co-homemaker,” says Lily Cheng, independent non-executive director of Swire Properties, Chow Tai Fook Jewellery, Octopus Cards and Sunevision in Hong Kong.

“Therefore, it causes family units to establish a binary division of labour (two roles: one partner works, the other is the primary caretaker) so one person stands the best chance of making it. And when division of labour is binary, then it will most often end up with men pursuing careers and women taking on the primary caretaker responsibility.”

Cheng, who won the leading woman director or executive prize in the American Chamber of Commerce’s 2023 Women of Influence awards, says there are several reasons for this, including “legacy stereotypes, personal preference [and] cultural acceptance”.

Time for Japan to come clean about gender pay gap to cut inequality at work

“If our workplace supported less binary divisions of labour, I think it would give everyone more choice to have the mix of work versus home that works best for themselves and their families.”

The matter of the gender pay gap long ago moved beyond discussion of pay discrimination based on sex.

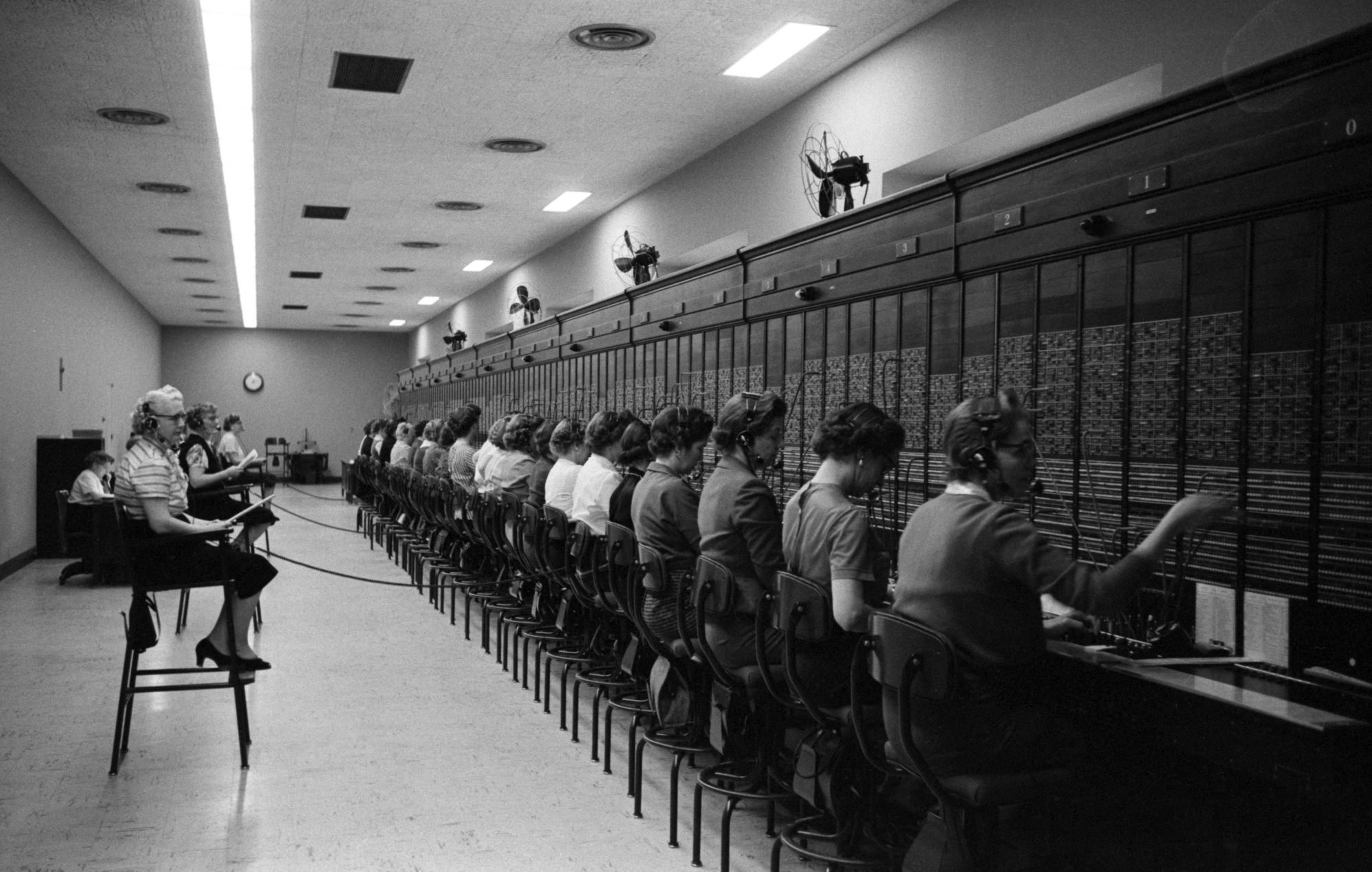

In the 1950s and ’60s, women in the United States were paid 40 per cent less than men, for many reasons: low education rates; low workforce participation; women being restricted to “feminine” jobs such as teaching and nursing; legal sex discrimination in the workplace; and cultural factors such as identifying women as home makers and being designated the task of raising children. (Hong Kong did not record such statistics at the time.)

The feminist movement over recent decades has helped narrow the pay gap significantly.

Why is a Hong Kong teen leading a UN talk on South African gender inequality?

In 2021, the female workforce participation rate in Hong Kong is 53.52 per cent, a little higher than the world average of 50.13 per cent. The ratio of female to male students in tertiary education is 1.1, almost equal participation, and closer than the worldwide ratio (based on 41 countries) of 1.17.

Hong Kong also has domestic helpers to help with household chores and child rearing. For a city of just under 2.7 million households, there are around 400,000 domestic helpers.

While the causes of the gender pay gap have shrunk around the world, the fact remains that women are still seen as primary carers, even when they hold positions of high authority.

As Cheng says: “In many cases that I have seen, many women operate under the construct that you can pursue your career as you like as long as you manage to handle the home too. We are lucky in Hong Kong to have access to domestic support and many women have managed to make it work with this high-wire act.”

Culturally, many workplaces still make it career-limiting for men to say that they need to take an afternoon off to take their kid to soccer practice or to take them to the doctor

Cheng believes the Covid-19 pandemic played a huge part in this widening gap. “When the pandemic came, this fine balance [of managing a career and home] broke down. When faced with the hard choice of work or family, many [women] chose to sacrifice their career aspirations and be there for their families during this time of need.”

Asked why women feel they should operate under this construct, Cheng says: “Maybe part of it is just the perpetuation of legacy stereotypes.”

Cheng’s experience is that gender equality cuts both ways. “Culturally, many workplaces still make it career-limiting for men to say that they need to take an afternoon off to take their kid to soccer practice or to take them to the doctor.

“My husband has been asked: ‘Where is your wife?’ when he said he needed to go tend to some family responsibilities. Men tell me that they would love to spend more time with their children and enable their other halves to build fulfilling careers and believe they can do so without compromising their work.

“However, some traditional corporate cultures stigmatise this behaviour from men as not being committed and not ‘all in’. In the age of artificial intelligence and advanced technology, this perception needs to change.”