To tackle climate change, fashion and biotech are combining to make clothes that are grown and breathe like plants

- London’s Post Carbon Lab uses algae and cyanobacteria to form a living layer on fabrics which sucks in carbon dioxide and releases oxygen

- Vollebak’s Plant and Algae T-shirt is grown in forests and labs, and can be buried when no longer wanted where it will break down

What role can fashion play in tackling climate change? A slogan T-shirt here, a recycled swimsuit there? How about harnessing biotechnology to create clothes that suck in carbon dioxide and release oxygen?

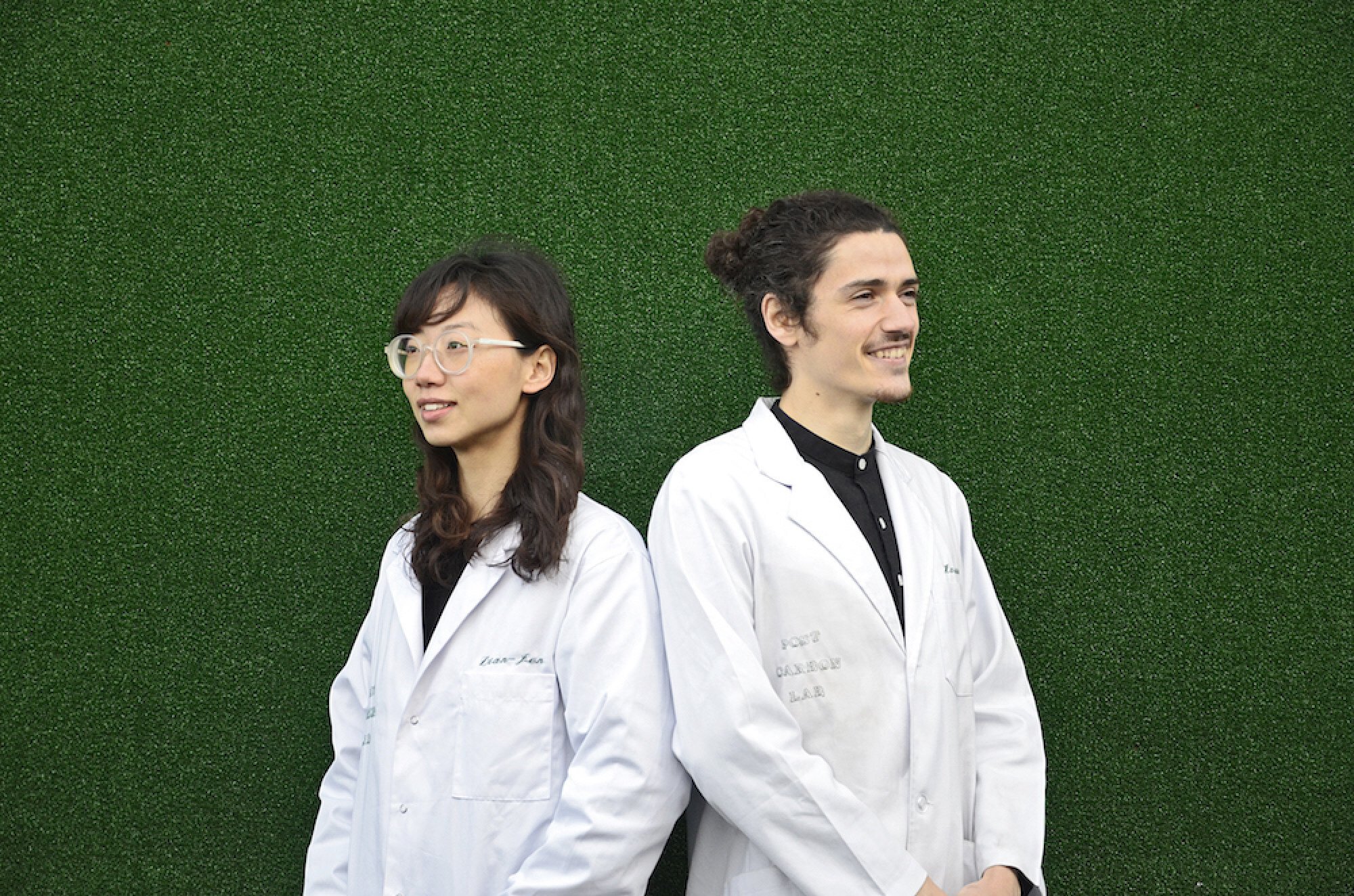

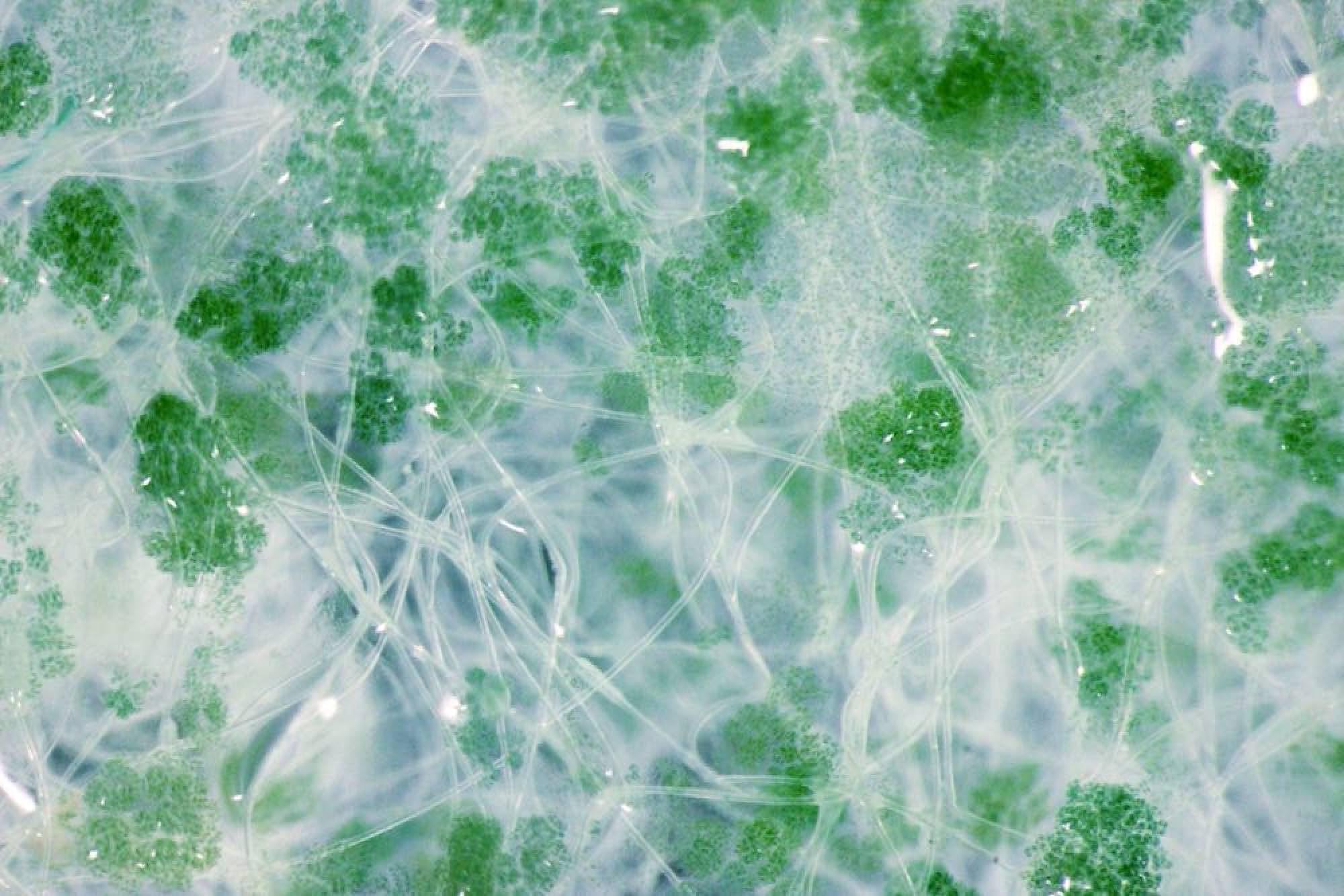

That’s the big idea behind Post Carbon Lab, an East London design research studio founded by Dian-Jen Lin and Hannes Hulstaert. Alongside their sustainability consultancy, they provide piloting services of microbial dyeing and a process they call photosynthetic coating, which uses algae and cyanobacteria to form a living layer on fabrics.

While it varies between items, the ballpark figure is that a T-shirt treated with this coating releases as much oxygen in six weeks as a six-year-old tree. However, it’s important to note that this data only reflects the part Post Carbon Lab can measure – that is, when they’re processing the item. Once it’s in the hands of the wearer, it’ll vary according to the care routine.

“Depending on which statistics you use, some people say fashion is the second most polluting industry [in the world], some people say it’s the fourth,” Lin says. “But it’s relevant to anybody who dresses. In that sense, fashion influences almost every single homo sapiens. If you were to use this medium not for negative effects but for a positive one, imagine that scale of influence.”

Lin pauses. Even over Zoom, her passion is palpable. “So that’s what we’re trying to do.”

Born in Taiwan, Lin studied fashion at Shih Chien University in Taipei and worked in various commercial roles. But, she says, “it became increasingly obvious that whatever I was doing was not good for the planet, nor for the people.”

That’s when she decided to step back and explore her alternatives. She recalls how she wanted to take a more artistic and experimental approach to fashion. Rather than pursuing fashion as a commodity – as a trend-led object to be traded – she started thinking about it as a medium for a message. “What would that look like? And then I did this master’s degree, which was focused on sustainability within the fashion world.”

That was London College of Fashion’s MA in fashion futures. Since then, Lin has led workshops, lectured at top universities, collaborated with the Natural History Museum in London, and won a Kering Award for Sustainable Fashion. All in the hopes of answering the question: what is the ecological role of the fashion industry?

For many brands, the answer lies in switching to organic cotton or using recycled polyester – what Lin describes as mitigation. For others, the answer lies in embracing technology.

For Vollebak, a brand founded by twin brothers Steve and Nick Tidball, it’s about creating clothes that acknowledge climate change. Whether it’s their fireproof, windproof and water-repellent 100 Year Hoodie (“built for a world that’s hard to predict”), or their solar-charged jacket, the British brand’s take on sustainable fashion is a little more… apocalypse-ready.

“Most of the clothing we make is based on questions that haven’t been asked of clothing before – like how are we going to sleep in space? Or can your clothes kill viruses? Or help you relax? Or light you up at night? Or store body heat?,” CEO and co-founder Steve Tidball says. “The Plant and Algae T-shirt is a great example. The idea is very simple. Grow the elements for a T-shirt in a lab and in a forest, so that it can be buried in your garden at the end of its life.

“But then you get to very practical realities. Like finding a commercial printer who is willing to take a bag of algae and put it in their really expensive printer to see if it works. So often the biggest battles we face are trying to do things where the supply chains aren’t set up.

“If you wanted to make a million cheap cotton T-shirts right now you could get it done in a month or two. But if you want to make even a small production run of something truly new, you have to allow two to five years, which is what it takes to make most of our clothes.”

Of course, not every brand has that sort of lead time. That’s where Post Carbon Lab comes in. It provides a service, rather than selling its own clothes because, as Lin put it, the greenest option isn’t a new sustainable T-shirt. “It’s the clothes in my wardrobe already!”

Yet as the millions of garment workers affected by the economic fallout of Covid-19 can attest, stopping all shopping isn’t the solution either.

“It is a much more systemic problem,” Lin says. “What we can do is help brands go in a better direction. We see ourselves as a catalyst and facilitator for brands to make those transitions and adopt more sustainable innovations. Then that has a ripple effect in terms of how the users have to form a different relationship with the garment.”

A different relationship?

That’s right. For clothes with photosynthetic coating, they’ll have to be looked after – much like a plant. So, don’t chuck it in the washing machine, but keep it somewhere airy with enough light and humidity. It’s a shift in mindset, granted, from “consumer” to “caretaker”. But imagine the change if we applied that to our planet.