US martial artist in China sees kung fu as preventive medicine and meditation, and documents his search for its origins

- Lawyer and government adviser turned documentary maker Laurence Brahm has studied many forms of Chinese martial arts to help overcome burnout

- His latest film documents his journeys across China to find the origins of kung fu, at the Shaolin Temple and beyond

As someone who practises kung fu for four hours every day, former New Yorker and international lawyer turned filmmaker Laurence Brahm is well-known in Beijing’s wushu community. He has studied under masters from various schools of Chinese martial arts, including 81-year-old Liu Hongchi, who is an expert in many wushu styles including Zhangjia Kungfu and Cha Quan.

“Kung fu trains your mind to think about opening up to opportunities, protecting yourself, avoiding conflict and getting hit, and creating situations where you can access where you want to be,” he says.

The 60-year-old reels off with pride the list of martial arts he practises, starting with a nod to his highly regarded teacher.

“Liu is very respected by every martial artist [in China]. During the Republic of China period, Liu trained under really old masters from the Qing dynasty. He teaches me Zhang family kung fu, an esoteric style of Beijing kung fu that dates back to the Ming dynasty, and the five traditional animal styles of Shaolin kung fu – the dragon, the snake, the tiger, the leopard and the crane.”

Not satisfied with simply learning kung fu, he delved into its history. He has just completed the documentary Searching for Kung Fu, sponsored by the Chinese Communist Party-owned English-language daily newspaper China Daily, in which he traces his journeys across China in search of the origins of kung fu.

The film follows Brahm’s pilgrimage to places including Chenjiagou (Chen village) in Henan province, where tai chi is said to have originated; the Shaolin Temple, also in Henan province, the cradle of Chinese kung fu; and Jingwu town in Tianjin, the hometown of Chinese kung fu legend Huo Yuanjia.

“At the Shaolin Temple, I was received by monk Shi Deyang who is the 31st Grand Master of Shaolin. We discussed martial arts and did meditation together,” Brahm says.

Kung fu taught a boy to walk. That was 60 years ago. Look at him now

“It was like returning home for me. I first visited the Shaolin Temple in 1981.

“There was hardly anybody there at that time. Most of the buildings had been burned down in 1928 by warlords. There was only the main hall, main gate and a statue of Bodhidharma. But it was a very important event for me as [I saw myself] going to the root of all of the martial arts.”

Brahm first visited China in 1981, when he studied Mandarin at Nankai University in Tianjin. A law graduate from the University of Hawaii at Manoa and with a master of laws from the University of Hong Kong, he went on to serve as a lawyer and Chinese government adviser on monetary policy and state-owned-enterprise reform.

He stopped commercial work in 2002 and started making documentaries. His first documentary, Searching for Shangri-La, was released in 2004, recording his hitchhiking quest across Tibet, Qinghai and Yunnan in western China to find the meaning of life.

Back pain, can’t sleep, feel chained to a desk? It’s burnout

“For Asian traditions, whether they are Hindu, Taoist, Buddhist or Confucian teachings, they are all about yin and yang (the idea that opposite or contrary forces may actually be complementary, interconnected and interdependent). Everything is about harmony, trying to find balance and attain oneness,” he says.

If we could get everybody in the US Congress to do tai chi every morning, they would have made much better decisions than they are making now

“From 2010 to 2013, I had very bad legs and difficulty walking. I was even disabled at one point. It got much worse when I filmed at very high altitudes. But I was able to recover entirely through doing martial arts.”

Kung fu is a kind of preventive medicine, he adds. “Many martial arts teachers are also Chinese medicine teachers and are very aware of their body’s condition. Chinese medicine and kung fu share one key thing, which is the importance of keeping your body fit and mind clear to prevent sickness.”

Brahm notes that the Beijing Wushu Association is working with the Chinese government to include daily tai chi every morning for government staff.

“If we could get everybody in the US Congress to do tai chi every morning, they would have made much better decisions than they are making now,” he says.

While wushu, the Chinese name for kung fu, is translated as “martial arts” in English with the word “martial” meaning military, Brahm says wushu is actually an art of non-violence.

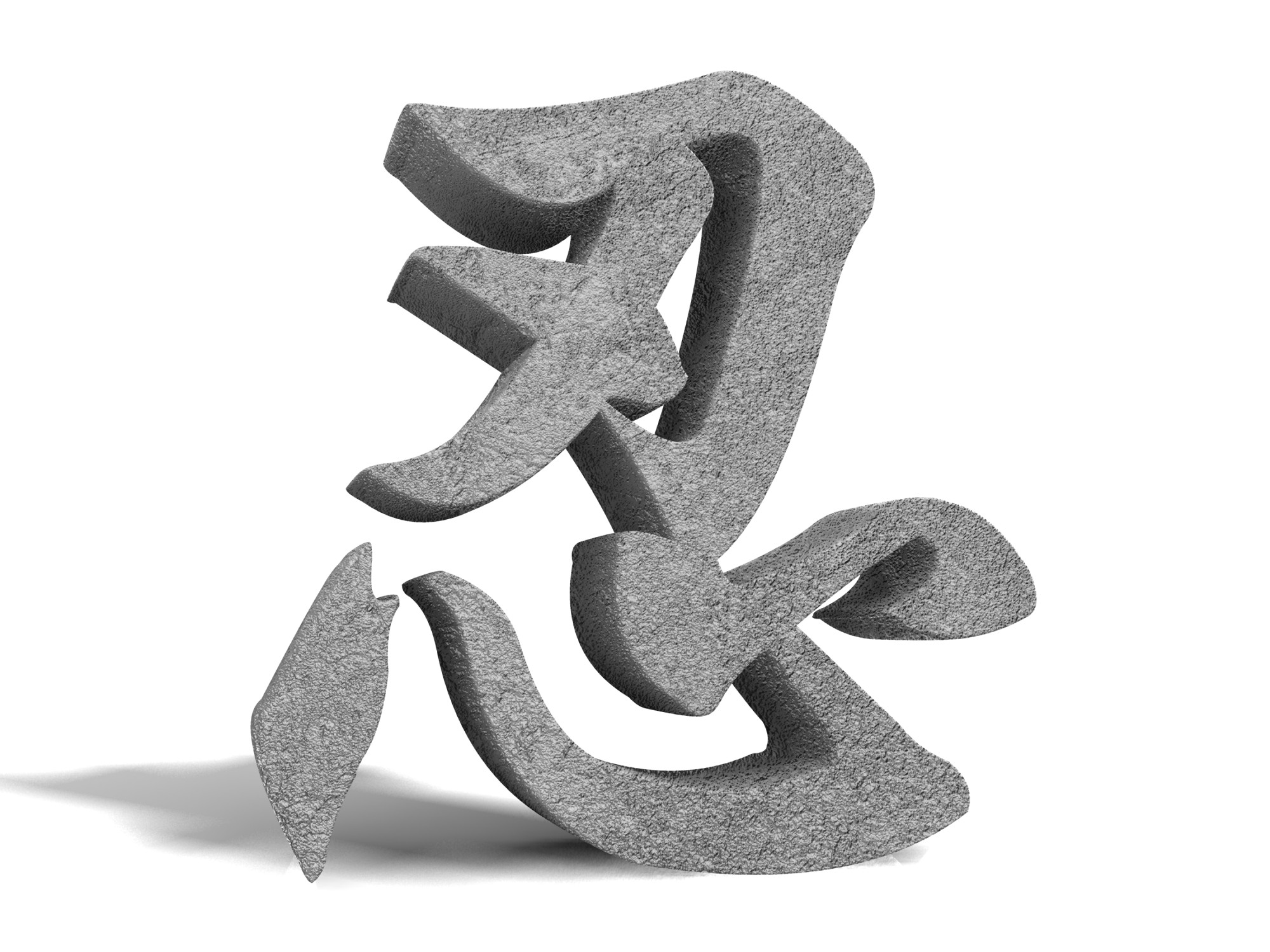

“There are multiple values inherent in martial arts – including loyalty, respect and the Chinese concept of ren or endurance. The Chinese character ren is made up of a knife over a heart with one more mark [on the knife] signifying blood.”

“What it really means is that you put your heart under enormous duress, but you are still able to endure. It is about consistent perseverance over time, which is a character of Chinese culture.”

He learned the value of “grounding” through Chinese kung fu, he says. “One of the key things in all martial arts is your stance or footwork. It’s not about upper body movement. The most important thing is your grounding. Culturally, too, we have to be grounded and understand our identity.”

Brahm’s goal is to film kung fu dramas which explore its underlying philosophy.

“Many feature films on kung fu today are about fighting. This is very artificial … I hope my drama features can reveal kung fu philosophies and reach a broader audience than a documentary.”