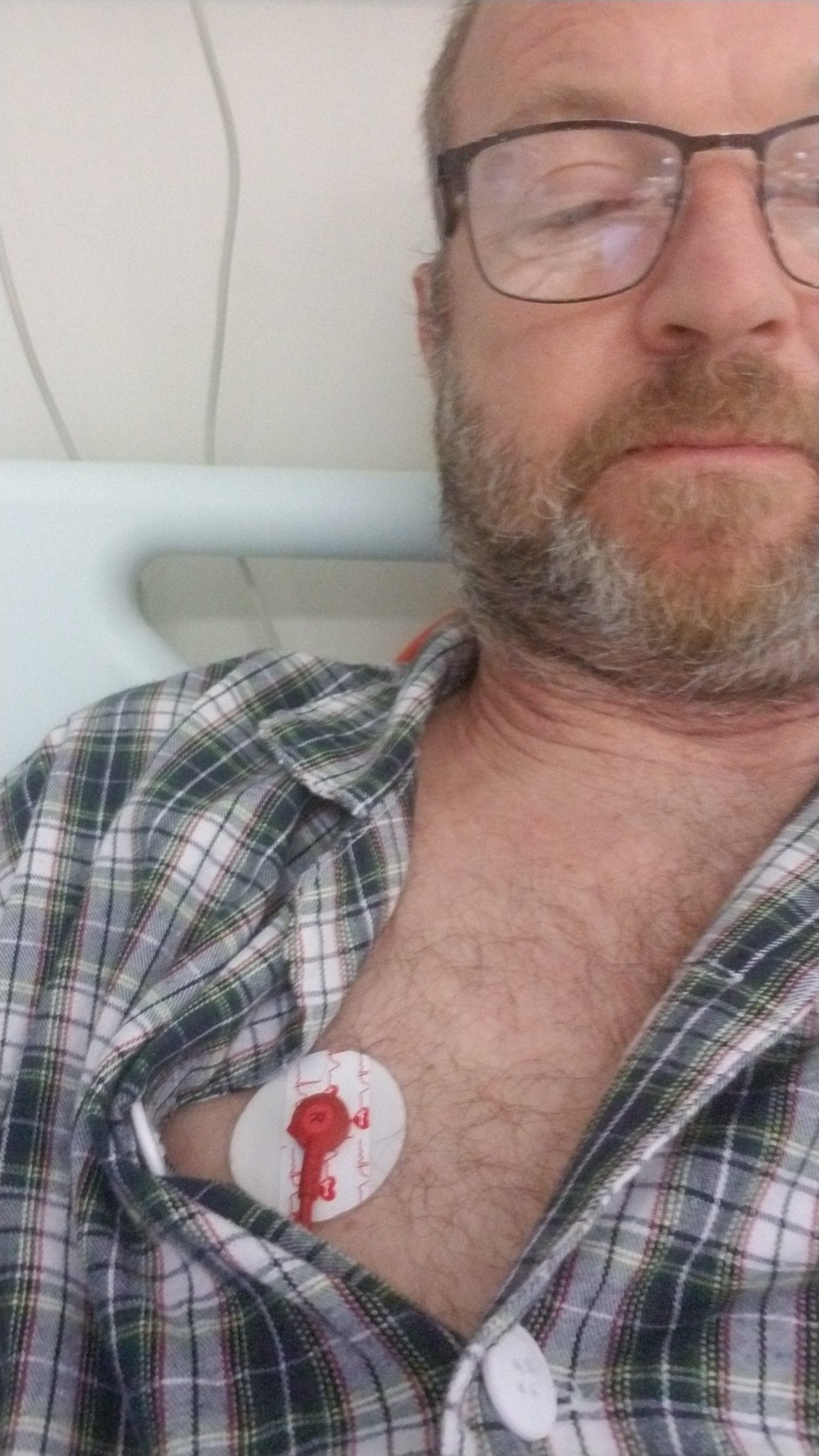

Diabetes emergency: a type 1 diabetic’s insulin overdose and his first-hand account of what he did to survive

- Type 1 diabetics produce little or no insulin, so regular injections are needed to keep them alive. But taking too much can have serious consequences

- The Post’s Simon O’Reilly accidentally gave himself a huge insulin overdose and knew he was in trouble. This is how the potentially deadly situation played out

Diabetes occurs when the body produces too little insulin, which is needed to process sugar, or cannot use it effectively. About one in 10 adults has this disease.

Type 1 diabetes, which accounts for 5 to 10 per cent of all cases, is a chronic condition in which the body produces little or no insulin. The other 90 per cent or so have type 2 diabetes; they produce insulin, but their system is unable to use it properly.

Living with type 1 diabetes is a balancing act. On one side is glucose, sugar in our blood, sourced from digested food, a major energy source for cells that make up the brain, muscles and other tissues.

In almost 30 years of living with type 1 diabetes, and around 37,000 self-administered injections, I had never messed up like this

On the other side is insulin, the hormone that allows sugar to pass from the blood into the cells. Too little sugar in the blood is known as hypoglycaemia, and the effects can be mild, serious or even fatal. A tiny amount of extra insulin (0.02ml) is enough to cause hypoglycaemia.

My insulin overdose

My normal insulin regimen is an injection of 30 units (0.3ml) of slow-acting insulin every morning, and eight units of fast-acting insulin with every meal. This mimics a healthy body: maintaining a low background level of insulin, and an increased level after eating to deal with the glucose in the blood.

One recent Sunday morning, I injected my usual 30 units of slow insulin. I didn’t eat for about another hour, and when I did, I should have had the eight units of fast insulin. For some reason, I accidentally injected myself with 30 units of fast insulin – almost four times the amount needed.

The insulin was going to use up all the sugar in my blood, leaving no fuel for my muscles or brain. A healthy person’s body will shut off its insulin supply, but a diabetic can’t stop the insulin once it’s injected.

I knew I was in serious trouble. I forced down a bar of chocolate, a large glass of milk and a bowl of cereal with more milk, but I knew it wouldn’t be nearly enough. In almost 30 years of living with type 1 diabetes, and around 37,000 self-administered injections, I had never messed up like this and was unsure what exactly would happen.

A glucagon injection can raise a diabetic’s blood sugar quickly, and even bring them back to consciousness within 15 minutes, but I didn’t have any at hand, and would still need hospital treatment given the amount of insulin I had injected.

I asked my wife to take me to the hospital accident and emergency department ASAP, where I paid the registration fee and told staff that mine was a serious medical emergency. Asked to sit and wait for my name to be called, I was hoping to be seen before I passed out. I tried to remain calm; getting excited would only accelerate the effects.

What is diabetes and why are so many people suffering from this disease in China?

Diabetics are given priority in hospital because of the potential severity of problems and the speed of their onset. I was called into triage after about five minutes, and explained the situation.

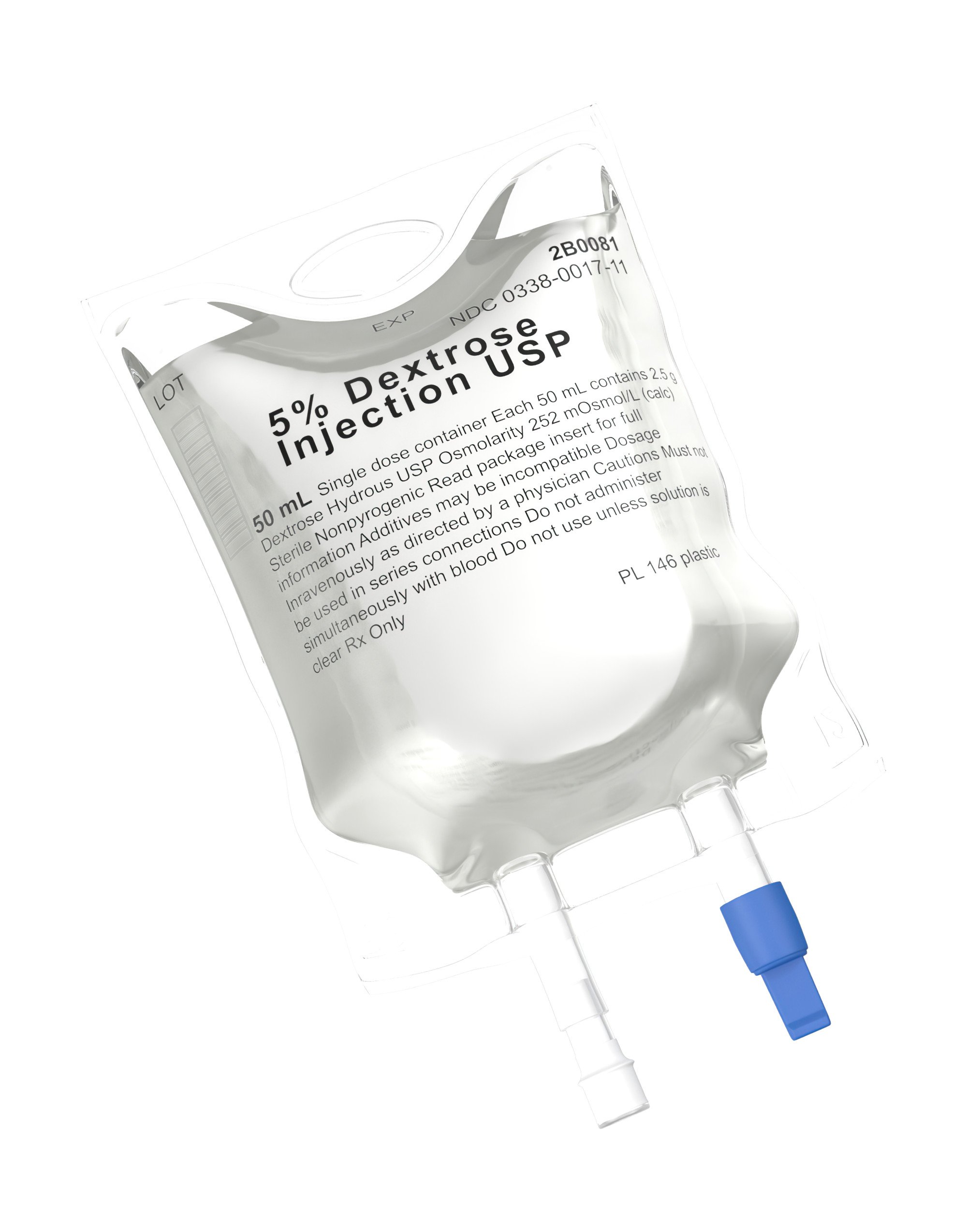

A nurse measured my blood pressure, took two syringes of blood for tests, and hooked me up to a dextrose IV drip. Dextrose is similar to glucose and is quickly taken up by the body.

My potassium level was measured. The adrenaline caused by the low blood sugar combined with the excess insulin lowers blood potassium levels, which can mess with heart rhythm. I was connected to an ECG and given a PCR test for Covid-19.

I was sat in a wheelchair to wait for admission to a medical emergency ward. The drip was feeding dextrose straight into my vein, so I was less worried about passing out. After an hour or so in triage, I was taken to a ward, still on the IV drip.

A nurse gave me half a dozen tests including one for Covid-19 (again), the antibiotic-resistant MRSA superbug, and another superbug called MRDA. The tests involved three nasal swabs, two throat swabs, two armpit/groin swabs, and – a first for me – a rectal swab.

After taking my blood pressure again, I was given a big booster IV injection of dextrose (50 per cent dextrose in water), and connected to a heart/lung monitor and left alone, apart from the regular blood tests.

My blood sugar continued to fall through the afternoon, despite the drip and booster injections of dextrose. Each shot was 50g to 60g of dextrose – the equivalent of a normal meal.

At around 6pm, I asked the nurses to check my blood sugar level as I was feeling dizzy and close to passing out. It was dangerously low and I was given another big injection of dextrose.

I avoid hospital food, and luckily I was able to order deliveries. When my pizza arrived, I wolfed it down. I was famished – a drip doesn’t fill you up. An hour later, my blood sugar level was in the normal range.

I was kept on the drip until late at night to ensure the last of the excess insulin had been countered. I stayed attached to the heart/lung monitor, but could disconnect the wires from stickers attached to my skin to use the toilet and stretch my legs.

I shared the ward with four other men, all elderly and all quite ill. Three were being fed through their nose, and the other was on a liquid-only diet. I won’t share any other details to respect their privacy. They were obviously in pain and groaned throughout the night. I had no physical or mental side effects, except boredom and lack of sleep.

The next morning, I had my usual dose of slow-acting insulin, but no fast-acting, and I ate breakfast. The next blood test showed high blood sugar, meaning the emergency was over. I was given my usual dose of fast-acting insulin, and by 2pm I was heading home, feeling none the worse for my experience.

Lesson learned from this: it is absolutely essential to get to hospital as quickly as possible in the event of an insulin overdose. Even with sugar being fed into my vein constantly, on top of breakfast and the chocolate, cereal and milk, I still needed large intravenous booster shots of dextrose, or I would have lost consciousness.

The danger zone was between 4pm and 6.30pm. Had I been alone and decided to treat it myself by eating – a terrible decision, but with low blood sugar, the brain isn’t working at full capacity, and the thought did cross my mind – I would have fallen into a coma, with a chance of dying.

How my blood sugar levels dropped through the day

Blood sugar is measured in mmols (millimoles); 4mmol to 7mmol is normal for a diabetic. For type 1 diabetics, a level below 3.9mmol is too low and can cause harm. A level below 3mmol calls for immediate action. (In the US, blood sugar is measured in mg/dl.)

Hospital admission 1.30pm. Blood sugar 9.1mmol. This is high because of the chocolate, milk and cereal I had eaten on top of breakfast.

2.04pm. 7.5mmol. Level is falling despite 30 minutes on a dextrose drip.

4.27pm. 3.4mmol. After two more hours on a dextrose drip, my blood sugar is still falling and entering the danger area.

5.39pm. 3.7mmol. After another hour and two dextrose injections, it has risen but is still too low.

How diabetes shapes one woman’s life, and warning signs to look for

6pm. 2.4mmol. Twenty minutes later, it’s dangerously low and another dextrose injection is given.

7.13pm. 6.3mmol. After eating a whole pizza and a box of chicken wings, and still on the drip, this is the first reading considered “normal”.

Monday 12.14pm. 17.4mmol. After 30 units of slow insulin and eating breakfast. Way too high. I was given a normal shot – eight units – of fast insulin.

I would like to thank all the staff at North Lantau Hospital in Hong Kong who looked after me. They were kind, friendly and extremely professional.