Rainforest restoration creates wildlife corridors and preserves habitats in southern India, but it’s a never-ending task

- The rainforest on the Valparai plateau in India’s Western Ghats was cleared for tea and coffee plantations in the 19th century, leaving only fragments

- When these fragments started disappearing, an NGO began work to restore and link them, creating wildlife corridors that allow animals and people to coexist

Birdwatching, they say, is largely about waiting. But on this cool, sunny spring morning, as we trek through fragments of rainforest on a trail in southern India’s Western Ghats, it seems as if one particular bird is lying in wait for us.

Whipping out of the canopy, it is exquisite, with its curved beak and black, white and yellow wings.

The great pied hornbill is native to Valparai and there’s a story behind its continued presence here, a tale of scientists and ecologists who, for two decades, have been working to bring these mini-forests back to life.

Valparai is best described as an inhabited plateau in the Anamalai Hills. It is like the hole of a doughnut, surrounded by scrubland, grassland and pristine forests.

To the north lies the Anamalai Tiger Reserve and to the south the Indira Gandhi Wildlife Sanctuary and National Park, with its fine teak and rosewood trees.

The plateau, more than 1,000 metres (3,3000ft) above sea level, is home to a cluster of villages. Visitors must negotiate about 40 steep hairpin bends to reach the plateau from the plains.

The Valparai plateau was a rainforest teeming with wildlife. But in 1864, as British colonialists were expanding across India, the trees were cleared to grow coffee and tea.

What remains on the plateau is a rather curious landscape, scientists say: more than 50 fragments of rainforest, mini-ecosystems sandwiched between coffee and tea plantations.

As commercial gain took over and tourism grew, what remained of those rainforests started disappearing, so in 2000, the Mysore-based non-profit Nature Conservation Foundation (NCF) began restoration work.

With a population of 70,000 people, the 220 sq km (85 square mile) Valparai is the site of one of India’s lesser known scientific experiments, a gentle transformation of the landscape by the NCF to make coexistence between humans and wildlife easier.

It began with the need to protect what was left of these rainforests, says Kshama Bhat, a former software engineer from Bangalore, Karnataka, who, in May 2019, arrived in Valparai to become part of the NCF’s growing team of scientists and wildlife researchers.

The foundation identified 50 fragments of rainforest worth reviving, but much of the land was owned by big private companies. The NCF had to engage with them, and sign memorandums of understanding that would release the land for restoration.

This was critical, because wild animals have to cross the Valparai plateau to travel between the protected forest zones around it.

“If these fragments didn’t exist, imagine how many humans they would encounter on the way,” says Bhat. “These green corridors were especially essential for elephants [the Anamalai Hills are also known as the Elephant Mountains], who are creatures of habit and tend to take the same paths.

“Today, the elephants stick to the more forested areas, making the villages and towns on the plateau safer for humans, because the chance of sudden encounters, which can be risky, is reduced considerably.”

We avoid one such encounter ourselves.

My cousins and I are staying at Stanmore Garden Bungalow, in the heart of the plateau and one of many colonial-era homestays run by Briar Tea Bungalows.

Stanmore is surrounded by tea plantations, but a short walk takes us into the forest and to the banks of the seemingly pristine Injipara river. On our second day, with the twilight fading fast, we are stopped by locals while walking the trail.

They’ve been alerted to elephant activity a little way ahead, they say, and we must return to our homestay. Everyone here is alert to the footfall of elephants; an SMS warning system launched by the NCF in 2013 helps spread the information.

For two decades, scientists and volunteers have been collecting the seeds of native species from the edge of the rainforest.

“We avoid collecting seeds from inside the forest because we don’t want to disturb its natural regeneration,” says Bhat. Those scattered along the roadsides, on the other hand, are not likely to survive where they have fallen.

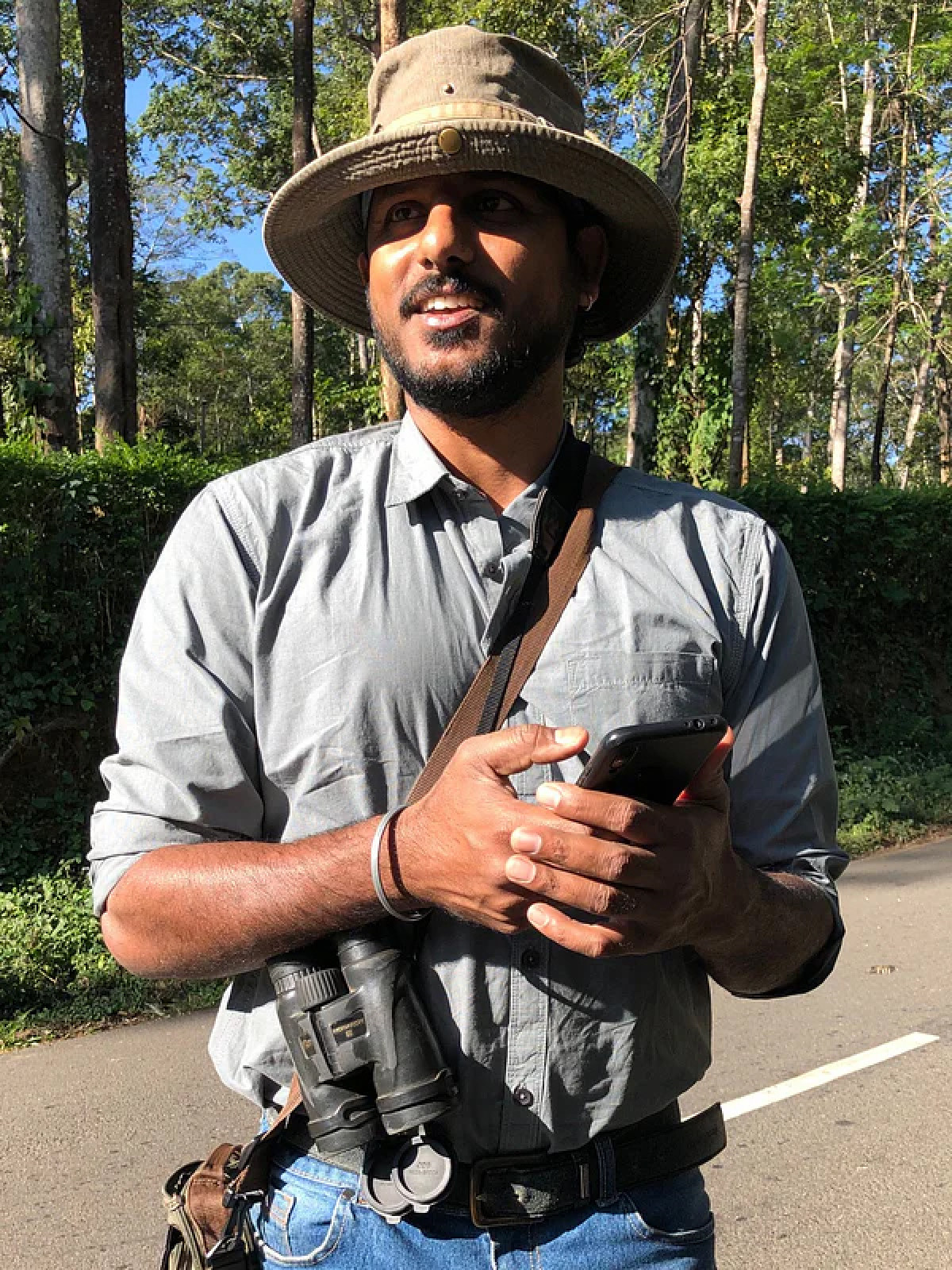

On seed collecting expeditions, Bhat is always accompanied by a field assistant from a local tribal community.

“They have a deep knowledge of the trees and forests,” she says. They know the terrain, which species is native and which is not, and can identify a tree by examining the colour and texture of its bark.

The team gathers roughly 30,000 seeds a year, but not all of them germinate.

“It varies depending on the species,” says Bhat, whose primary responsibility is to maintain NCF’s nursery. “Elaeocarpus munroi [a flowering plant endemic to India], for instance, has a very low germination success rate. If I sow 1,000 of these seeds, five or six would germinate and they take six to seven months to show any signs of life.”

The nursery contains between 80 and 120 species of tree at any one time, and saplings must be transported to restoration sites that can be up to 30km (18 miles) away.

“We do five to seven hectares [12 to 17 acres] in a year, planting about 5,000 to 6,000 saplings,” says Bhat. “Survival [rates] can range from 40 per cent to 80 per cent, with a lot of bald patches.” After between seven and 10 years, the team will do a round of infilling, she says.

The saplings also need to be monitored. A typical day for Srinivasan Kasinathan, a restoration ecologist who has been monitoring NCF’s restoration plots since 2015, involves studying the saplings and observing changes that have happened to the forest over time.

Once deforestation happens, restoration will not magically bring back everything that was lost

Furthermore, “We keep visiting the sites [ …] to remove invasive species,” he says.

Kasinathan wages a constant battle against plants such as Lantana camara (shrub verbena, which is thorny with orange flowers) and Sphagneticola trilobata (a creeper with yellow flowers which covers the ground in a thick mat). Frequent weeding is required to keep the invasive species under control so that they don’t hog the ground’s resources.

Invasive species are persistent here because young rainforests are not protected by a fully formed canopy. A canopy acts as a protective covering for the plants below, shielding them from intense sunlight, drying winds and heavy rainfall, and sealing in moisture. A canopy-protected environment helps new plants establish themselves.

Twice a year, the scientists photograph and document the restoration sites, recording how the vegetation changes. In this work, local tribespeople are a godsend, says Kasinathan, not least because they are experts at differentiating native species from invasive ones.

Dr Anand M Osuri specialises in rainforest ecology and restoration. He has worked on the restoration project with NCF since 2017, and is now involved in assessing whether these microhabitats are reviving.

One of the things he measures is diversity, and he is encouraged to find that the forest patches are starting to attract wildlife that can disperse seeds naturally.

Osuri also measures carbon capture. “The carbon that is trapped within the trunk, branches, roots and leaves of a tree is the carbon stock,” he says.

“Carbon stock largely depends on two things: the size of the tree and the density of its wood. Hardwood trees have more carbon per unit volume being held within each tree than the softwood trees.”

Osuri compares the areas where the restoration work has been carried out with patches of forest that haven’t yet been touched, and has found that the restored fragments have several times the amount of carbon stock.

However, even 20 years of restoration cannot replicate the carbon stock of a mature rainforest.

“Once deforestation happens, restoration will not magically bring back everything that was lost,” says Osuri.

That is a lesson for Asia, he says, which tends not to value its forests. Governments in many countries feel that destroying an old forest for development won’t do any ecological harm if a new one is planted in its stead. But young trees don’t hold as much carbon, nor provide the same canopy protection.

Restoration is a painstaking process that can take many decades to deliver results. Nevertheless, consistent efforts in Valparai are showing results; the soil is recovering and the canopy cover is growing back.

But the biggest evidence of success lies in the mighty, beating wings of a highly endangered species whose habitat is threatened by deforestation but whose numbers in Valparai are beginning to rise: the great hornbill that so enthralled us all on that bright spring morning.