- Desperate to escape the fallout of the Cultural Revolution, swimmers braved deadly cold water, sharks and police patrols to reach the bright lights of Hong Kong

It was about midnight when Poon Yuen-ching and her fiancé, Lo Ping-sum, stood at the edge of Deep Bay. Some 5km (3 miles) away, across the cold waters, the prospect of a married life in the British colony of Hong Kong awaited, free from the poverty and political turmoil wrought by China’s Cultural Revolution.

The 22-year-old students had trekked nine days to reach this point, from their homes in a fishing commune in Dongguan, 40km away in Huangjiang, evading frontier guards along the way and hiding in bushes whenever flares were fired. They were well prepared for the swim to economic and political freedom: Lo had won several swimming championships at school, while Poon trained each night in secret for the 10-hour swim.

The couple had dated for three years before being separated when they were sent to the fishing commune under the Cultural Revolution, local media reported at the time. Poon told Chinese-language Hong Kong newspaper The Kung Sheung Daily News that working 12 hours a day fishing in peak season, followed by hours of learning the words of Mao Zedong, was too tough.

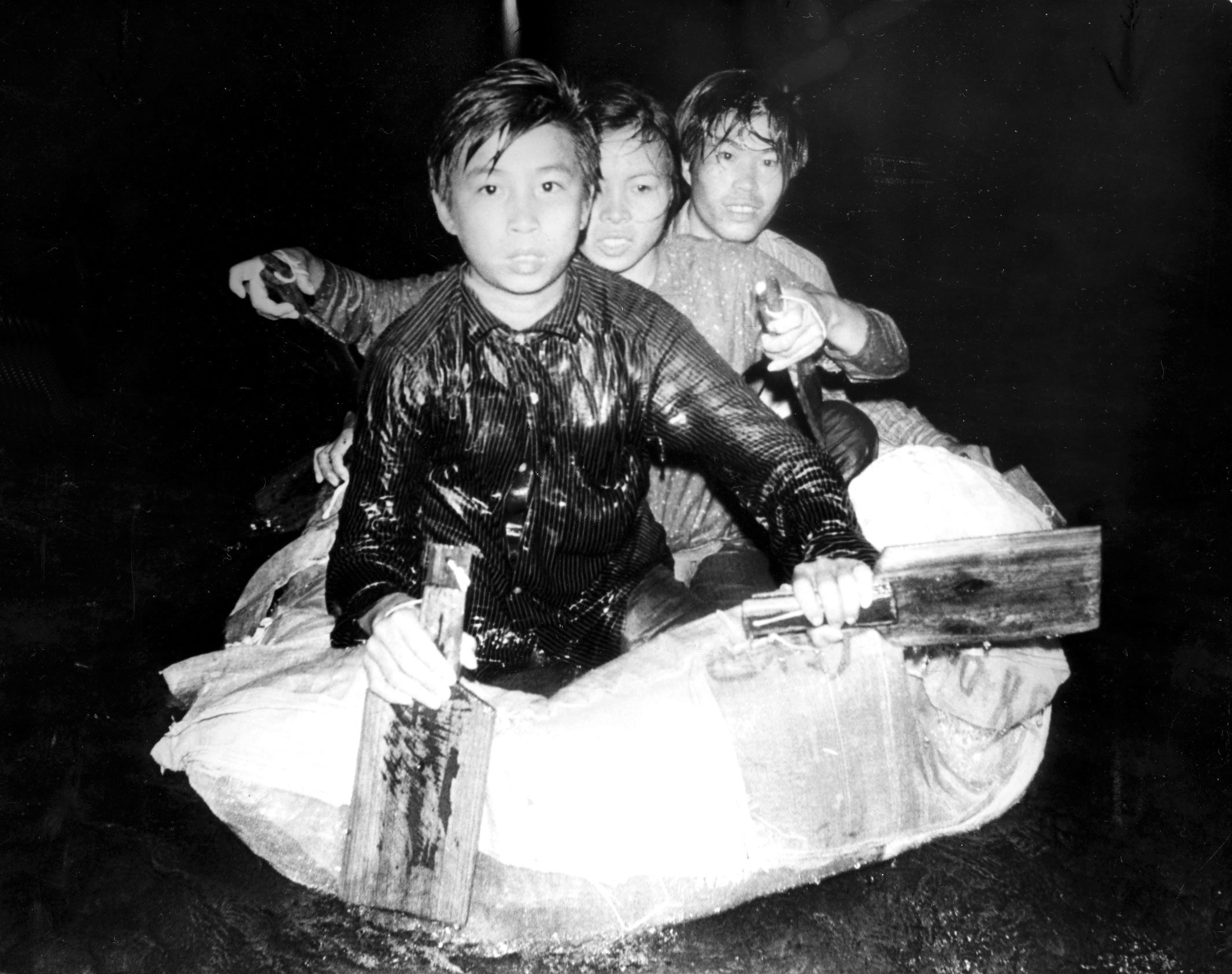

The pair entered the water during the first hour of November 10, 1970, holding on to rubber bladders in order to stay afloat in the strong current. After 50 minutes, at around 1am, Poon heard her fiancé shouting that it was too cold, asking her to swim faster.

An hour and a half later, Lo was trembling, telling her he could not make it to the other side. Poon strapped the two rubber bladders she had onto Lo, but it was too late. He had fallen unconscious. Poon tried to resuscitate him, but nothing worked.

For the next six hours, she held onto her fiancé with her left hand and paddled with her right, while picking at her numerous cuts and bruises, likely from the oyster beds. A Hong Kong police boat eventually came to the rescue, lifting the pair from the water and ferrying them to a beach in Tsim Bei Tsui, off Lau Fau Shan.

Poon stepped out of the boat and her fiancé’s body was removed. She was sent to hospital and discharged the same day, before being questioned at the Yuen Long police station and released to live with a relative in the city.

The Kung Sheung Daily News reported from the scene that Poon wore sunglasses and covered her face with a handkerchief to avoid being photographed, telling the paper she was worried that having her face in the press would hurt her prospects in the city she had sacrificed so much to come to.

Lo’s body, meanwhile, was moved to the Kowloon Public Mortuary, later to be buried in Wo Hop Shek Public Cemetery.

This couple were but two of the estimated millions who fled to Hong Kong to escape mainland China between the late 1950s and early 80s. Following the end of the Great Leap Forward in the early 60s, illegal immigration to Hong Kong from mainland China rose to a peak in the late 70s, by which time local sentiment was less than sympathetic. The South China Morning Post ran a front-page story in 1974 headlined “Refugees a big strain on our resources”.

“The flood of refugees from across the border is in fact putting an intolerable strain on the ambitious plans of the Government to make life better for the Hongkong man-in-the-street,” the article read.

Official figures show that nearly 90,000 illegal immigrants were arrested in 1979 and more than 82,000 in 1980 but still they came in droves. The main reason being that between 1978 and 1980, more than 155,000 were allowed to stay, and millions of refugees have long laid down roots in the city.

Among them is 62-year-old Lee Yat-keung. Lee had initially been coy about discussing his ordeal, believing that escaping to Hong Kong could be seen as shameful, a betrayal of state and family. He agreed to talk only after considering what he and the other “freedom swimmers” have meant, and more, what they have contributed to Hong Kong.

Lee came of age during the Cultural Revolution, the 10 years that deified Mao Zedong and ended with his death, in 1976. One trait of this period was the “revolutionary mass campaigns” that violently challenged those who had held positions of authority prior to the Communist Party’s assumption of power in 1949.

In Lee’s native Guangzhou, Cantonese teahouses, hair salons, shops and hotels had lined Shangxiajiu until the Cultural Revolution forced most of the businesses on the shopping street to close. Banners and slogans painted in red covered the shopfronts, denouncing class enemies and praising supreme leader Mao.

Students blew the whistle on their teachers for being counter-revolutionaries, as did children on their parents. When captured by Red Guards or by civilians devoted to Mao’s revolution, these “enemies” were hauled off to “struggle sessions”, paraded down Shangxiajiu to be denounced by the public.

“In that political climate,” says Lee, “people were very afraid.”

The devastating infernos that forced Hong Kong to form proper fire services

So in 1979, aged 18, Lee started to plan his escape. And he was not the first in his family to make the attempt. His father had left for Hong Kong in the 60s, having been starved during the Cultural Revolution. If his father could do it, he could, too, thought Lee.

“Once people know that you are thinking about crossing the border to Hong Kong,” says Lee, reflecting on his past from a wooden cabin at a glamping site only kilometres from where he came ashore more than 40 years ago, “your head will be shaved bald and you’d have to march down Shangxiajiu with a board hanging from [your neck, with the alleged crime written in oversized red characters].”

Fear of a struggle session did not deter Lee from training every day for his escape. For three months, he swam 4km from Haizhu Bridge at the centre of Guangzhou – then home to 4.8 million people, a far cry from today’s 18.7 million – to Shiweitang Railway Station at the city’s edge, then took the train back. The swim took six to seven hours.

Leaving for Hong Kong was a trend among the youth of 1979. Lee and others who lived in Guangdong had heard tales of extravagant lifestyles down south. Those who had escaped sent money back for their families to build houses, and when they would come back to visit they brought luxury items such as refrigerators and television sets.

“It was huge,” Lee says. “Young people, around 18 or 19 years old, all wanted to escape. Chinese society was poor and undeveloped. A closed society had created many problems, which made all the young people on the mainland – especially those near the Pearl River Delta – long for Hong Kong.”

Before the Cultural Revolution, Lee had spent his early years living under another of Mao’s campaigns – the Great Leap Forward. At the age of two, Lee was already toddling in his wooden sandals to the communal dining hall of his people’s commune, carrying a small bowl in which to collect his share of rice.

Intended as self-sustaining communities with clinics and schools to support industrial and agricultural production, the commune system collapsed under unrealistic production goals and inflated production figures. At least 15 million people died from famine during the Great Leap Forward, from 1958 to 1962, according to the Chinese government. Other estimates are higher.

My dad told us they were victims of a disaster. We couldn’t ask them for money. We had to help them as much as possibleKen Cheng of Ha Pak Nai village, where waves of mainlanders sought shelter

Frank Dikötter, China historian and chair professor of humanities at the University of Hong Kong, puts the figure at 45 million deaths.

“That gave me a sense, when I was very little, to yearn for freedom,” Lee says. “That pushed me to work hard and earn what I deserve.”

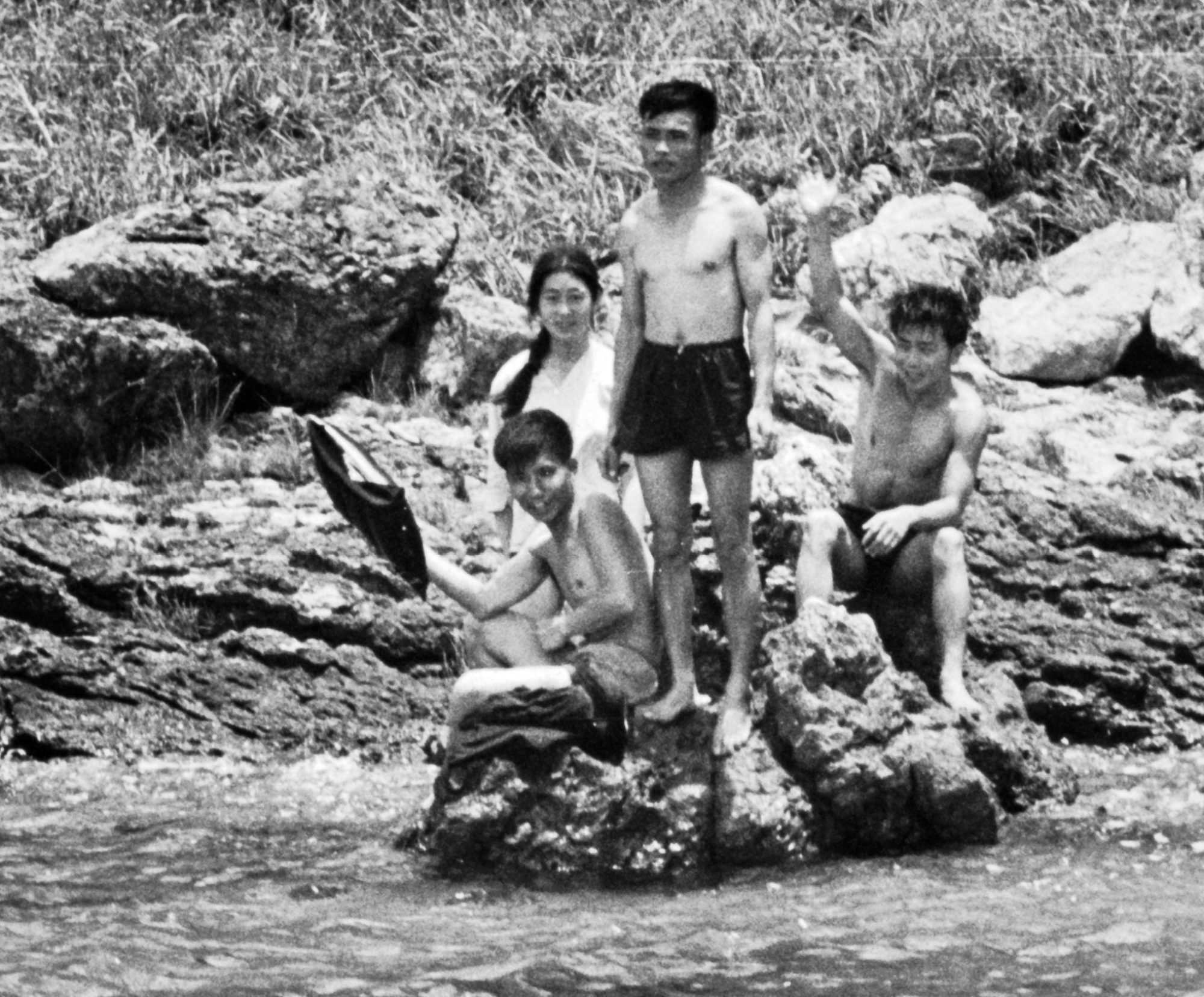

On July 25, 1979, he and two other “Guangzhou boys” took a train east to Shilong town, carrying documentation that two other friends had signed for them, allowing them to board the train.

In Shilong, the five youths planned their escape route. Setting off the next day, by bike and then on foot, they eventually arrived at Nantou, on the west side of modern-day Shenzhen, then a county of 360,000 people but today a metropolis of 17.6 million.

“We definitely could not walk during the day, because there were militia and soldiers at the border,” says Lee. “The militia won’t talk to you, but the army at the border will shoot you.”

Another 10km would bring them to Futian, where the northwestern Hong Kong coast was visible across Deep Bay. It took the boys three more nights to hike there, and Lee carried only a dim kerosene lamp to navigate through fish ponds, farmlands, ditches and oyster farms.

At around 11pm on July 29, they reached the shore. Dropping everything, they stripped down to their briefs, ate the last of their rations and, after blowing up an inflatable pillow, Lee stared out across Deep Bay.

“The sea looked basically like a road to death,” he says. “I thought, ‘The sea is so wide, how am I going to make the swim?’”

Lee knew he was to climb out of the water in Lau Fau Shan, in northern Hong Kong, but had no idea what it looked like. “We just knew it was a place full of lights – like a rainbow. That strengthened our belief that we could make it,” he says.

Lee embraced his friends briefly before entering the water. He clung on to his buoy as he tried to navigate in the dark, wearing only his briefs and a belt tied to a plastic bag holding his dry clothes and a golden ring his mother had left him. He quickly found it was easier than his training swims in the Pearl River: the salt water of Deep Bay helped him stay afloat.

At one point, two people came into view, floating towards Lee, and he thought they might be migrants like him. One had long hair. Lee swam up to them and yelled: “Move on, hurry up and swim faster.” Then he saw that one of them was dead, and when the other came by, they were already bloated like a balloon.

“I got very emotional,” he says. “Why did us young people have to die in the sea just for the sake of striving for a better life?”

From the mid-70s to the early 80s, bodies were found daily, floating just beneath the surface, says Les Bird, a former marine police commander. Strong winds pushed some out into the ocean, others lost grip of the pillows, tyres or inflated tubes that kept them afloat.

They also had to avoid propellers, and in Mirs Bay, in Hong Kong’s northeastern waters, there were sharks. Some died from hypothermia in the winter. Some couldn’t swim in the first place. Local fishermen often pulled up bodies caught in their nets.

After eight hours, only thinking to keep swimming towards the lights he could now see, Lee climbed out of the water at Tsim Bei Tsui.

“I came back from the dead,” says Lee. “I had to leave socialism. I hated that form of life. If I were to die I would rather die in the sea. That was the deal. I saw very bright lights, like stars, which gave me determination that was one of a kind.”

Only two of Lee’s friends reached the shores of Lau Fau Shan with him. “Two of my peers, who were my best childhood friends …” Lee fights back tears describing the two who didn’t make it. “At this point, it has been 41 to 42 years since they died and their bodies have never been found.”

The surviving trio were exhausted, but they had to find somewhere to stay in order to avoid being arrested by border police. They trekked cautiously, carrying with them two dried pieces of tiger faeces they had stolen from the Guangzhou Zoo to ward off the German shepherds that patrolled with the Gurkhas, Nepalese nationals who served in the British Army as elite soldiers and whose duties included tracking illegal immigrants, rescuing flood victims and clearing roads after typhoons.

“We’d heard the [dogs] would flee when they smell tiger faeces,” says Lee, “so we were prepared.”

The story of Watsons: from licensed opium dealer to Asia’s biggest pharmacy

Crossing oyster farms to reach a local village, the jagged shells cut into their legs under the thigh-deep water. Lee says he didn’t even notice at the time, the “indescribable” pain came later. There, a Tang family made them instant noodles, let them shower and allowed them to stay in the pigsty.

Ken Cheng Wai-kwan, the representative of Ha Pak Nai village, grew up there, and had observed the waves of mainlanders seeking shelter since he was around five, in the early 70s. Cheng was raised poor in his village by Deep Bay, he says, but that did not stop his father from cooking a large pot of rice, or buying barbecued pork in takeaway boxes, when swimmers came to them for help.

“I’d say… each person ate five to six bowls of rice on average,” Cheng recalls. “They were really hungry.”

Cheng says he would see local authorities fill two hearses with bodies from the sea every day. He didn’t need to wait for the swimmers to knock on their doors to know they were out there. Dogs raced up and down the shore barking at night as helicopters shone their spotlights on them and Gurkhas gave chase.

“My dad told us they were victims of a disaster. We couldn’t ask them for money,” he says, “we had to help them as much as possible.”

But Lee was not so fortunate upon reaching the Tangs. “We thought they were so kind but we didn’t know that actually we had to pay for it,” he says. They knew nothing of the “snakehead fees” charged by those who helped smuggle people across the border. These could run to as much as a few thousand Hong Kong dollars.

On being asked to pay for the noodles and the pigsty shelter, Lee phoned his father, who lived in Lok Ma Chau, in north Hong Kong, and who sent a car to pick him up from the Tangs.

To stay in the city, Lee knew he must declare his presence at a police station. He got into the Mercedes his father had called for him and was taken to Possession Point on Hong Kong Island, where his aunt lived. Unlike minibuses and taxis, police would not inspect expensive cars, says Lee. At the time, he says, he didn’t know what a Mercedes was.

In many, many cases it was hopeless because of all the disadvantages they faced trying to come across: the cold, the long swim, the sharks, the patrols on both sides. But hope was always in their eyesLes Bird, former Hong Kong marine police commander

As it turns out, Lee was one of the last benefactors of the “touch base policy”, which from 1974 allowed illegal immigrants to stay in the city if they evaded authorities to reach urban Hong Kong, and could either stay with relatives or had found a formal residence. It was a “very British, ‘sporting’ approach to a unique international problem”, said Dr Ronald Skeldon, then a geography lecturer at the University of Hong Kong, describing the policy in 1986.

It replaced the previous unrestricted entry policy, specifically to curb the growing number of immigrants fleeing the Cultural Revolution. Official figures show 6,600 mainlanders entered Hong Kong unlawfully in 1977 and evaded arrest. Two years later, the figure ballooned to 102,000, and the policy was scrapped in 1980.

“The message must get back to, and be understood by, the young people in the communes, that illegal immigrants are not welcome in Hong Kong,” the city’s then No 2 official, Chief Secretary Jack Cater, said, “that from now on life for them in Hong Kong will not just be unpleasant, it will be intolerable; that sooner or later they will be detected and they will be repatriated.”

Ensuring that swimmers were captured and returned to the mainland was part of keeping Hong Kong prosperous, and preventing rampant population growth, says former marine policeman Bird, as waves from Deep Bay lap against the shore in Ha Pak Nai. The cable-stayed Shenzhen Bay Bridge that stands behind him did not exist the last time he visited the area, more than three decades ago.

“There had to be some kind of checks and balances, and what we did was part of that. It was sad, but it was necessary.”

Bird’s first patrols in the bay were done only by moonlight, to avoid being seen by the swimmers. The police boats patrolled in low gear, almost drifting through the darkness. Night vision devices coloured the world green and black for Bird and other officers.

“The atmosphere was silence, tension and then, of course, when you actually catch them,” he says, “this sadness and fatigue.”

Bird left the force in 1997, but recalls clearly the first swimmers he helped to capture, teenagers in a party of five or six, all close to drowning. Bird says “it was more of a rescue than an arrest because they’d realised how difficult it was and were in difficulty themselves with the cold, with the fatigue.”

Despite being given food and clothes on the police boat, most swimmers were reluctant to talk. They might offer their name, age, where they came from or how long they had been travelling, but, Bird says, they were all too scared to say much else.

Bird came to Hong Kong in 1976, in his early 20s, not much older than the swimmers he was ordered to stop in Deep Bay and Mirs Bay. That his first job was to catch people of his own age, who were, like him, striving for a better life in the city, was, he admits, an “odd dynamic”.

The patrol, from dusk until dawn every night, while not physically demanding, was mentally challenging for those officers who counted “freedom swimmers” among their families.

“For them it was a double dynamic emotional thing,” says Bird, “because they were sending people back [who had tried to come to Hong Kong] the same way as probably their fathers or their uncles had.”

Philip Li Koi-hop, a former marine police sergeant, says that he sympathised with the swimmers, but orders had to be followed. “We couldn’t be overly sympathetic,” he says. “We needed to balance the two and we did what was most appropriate: to give them a way out and help them as much as we could.”

Some mainlanders who came from Mirs Bay boarded sailing boats, which could barely sail by the time they were intercepted by police. “It gets pretty scary when you just shine a light across the bay, and you see them all over the sea,” says Li, who patrolled the area from 1980 to 1981. Around the Mid-Autumn Festival, Li remembers, the escapees carried mooncakes, which would become soaked with seawater.

Once apprehended, police put their “catch” – sometimes dozens of people – on a launch headed for the mainland at first light, after a last sweep at dawn. Those picked up in Mirs Bay were taken to Sha Tau Kok Pier and escorted to the border crossing, where members of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) waited at an arranged time. The Hong Kong police spoke no words to the PLA.

“A clipboard with a number on it and the names, gender, ages would be handed over, and we would turn around and just go back and that would be it,” says Bird.

I’m turning 62 and I am very grateful and thankful to the heavens, and thankful towards Hong Kong, this palace, for giving me shelter‘Freedom swimmer’ Lee Yat-keung

Book Keng-kwan, a glass company owner who swam to Hong Kong when he was 19, in 1979 after two attempts, says troops in Shenzhen caught him on his first try. He was sent to a cell for three months in Zhangmutou, Dongguan, where he’d started his journey by foot. He and about 20 other people were held at a facility without toilets and fed only two meals a day.

He was released after his family was notified. “The local authorities at the time didn’t make it hard for you,” says Book, “as everyone knew about the trend among young people trying to find a better life for themselves in Hong Kong.”

But Bird always saw hope in the swimmers, even when captured.

“In many, many cases it was hopeless because of all the disadvantages they faced trying to come across: the cold, the long swim, the sharks, the patrols on both sides,” he says. “But hope was always in their eyes.”

Lee says that coming to Hong Kong, “there was only one thing in our minds, which was to improve our lives, thrive and work hard”.

The history (and debauchery) of Hong Kong’s Foreign Correspondents’ Club

He got his first job in Hong Kong working for the wholesale department of a department store that sold Chinese products, and earned HK$350 a month. By night he studied for free at a school set up for the working class in North Point under a government scheme.

Across the border, a senior member of staff would be paid HK$60 to HK$70 a month, he says. “So it was a pretty big deal for us to be earning hundreds of dollars.”

In 1988, Lee started his own small engineering business making keys, fixing pipes and repairing electrical wiring. Keung Kee Engineering still stands on Waterloo Road, in Yau Ma Tei, a bustling commercial centre in Kowloon. He has raised three daughters: a teacher in her 30s, another working in the finance industry and his youngest, a medical student.

“I am very satisfied, because I have my own property in the city centre, and back in Ha Pak Nai, I have a place to live,” he says. “The most important thing is that you have food to eat, you are safe and you have a job.

“I came to Hong Kong when I was young and I have contributed to Hong Kong for 42 full years. I’m starting to get old now,” he says with a grin. “I’m turning 62 and I am very grateful and thankful to the heavens, and thankful towards Hong Kong, this palace, for giving me shelter.”

Today, Lee stands once again at a mangrove-filled beach in Ha Pak Nai, not far from where he left the water more than 40 years ago, as families enjoy the weekend on the sand. Behind him are the oyster farms that injured so many of his fellow swimmers, and further in the distance stand the glass-walled skyscrapers of a Shenzhen so much changed from Lee’s last visit.

In this view, there is an irony that is not lost on Lee. After decades of disastrous policies that drove millions into poverty, many lives have vastly improved in mainland China. These days, Lee says, people he knows speak of Hong Kong trailing behind.

“Relatives back in my hometown sometimes say if I hadn’t left for Hong Kong, I could have become a dakuan – what a rich man is called on the mainland. ‘Isn’t it good to be a dakuan?’”

Ken Cheng, the villager who grew up sheltering “freedom swimmers” in Hong Kong, feels the same way, saying those who came to Hong Kong made a mistake.

“It turned out to be wrong,” says Cheng. “Apparently even if you have worked for so long in Hong Kong, your whole working life, you would be considered poor when you return to the mainland.”

After four decades, Lee is going nowhere, but even now, the story of his escape has been hard for him to tell. In part, he says, because he still harbours a fear of being discriminated against in Hong Kong as a mainlander. The other reason is shame.

“I don’t wish to tell others of the bad things that happened to me,” he says. “I don’t want to be exposed that much, about what this person went through.”