When a Cathay Pacific plane became victim of world’s first hijacking of a commercial flight

‘Four millionaires went to their deaths’ when the Catalina plane went down en route to Hong Kong.

“There is little hope of the survival of 26 passengers and crew of the amphibious Catalina plane belonging to Cathay Pacific Airways, which crashed into the sea near Macao late on Friday afternoon,” reported the South China Morning Post on July 18, 1948.

“As far as we know, they have all perished,” A.J.R. Moss, director of Civil Air Services, told the newspaper.

“Four millionaires went to their deaths in the crash […] the Macao Police Commissioner, L.A.M. Paletti revealed today,” the Post reported on July 26. “The wife of one of the millionaires, Paletti said, told him that her husband carried with him over $500,000 when he boarded the plane.

“This, Paletti implied, was [a] link in the piracy theory now being advanced as the cause of the disaster. [He] said that a pirate gang might have plotted to force the plane down, capture and ransom the four wealthy men. He added that of the five men suspected of being involved, one was a Chinese air pilot, who was on the plane when it crashed.”

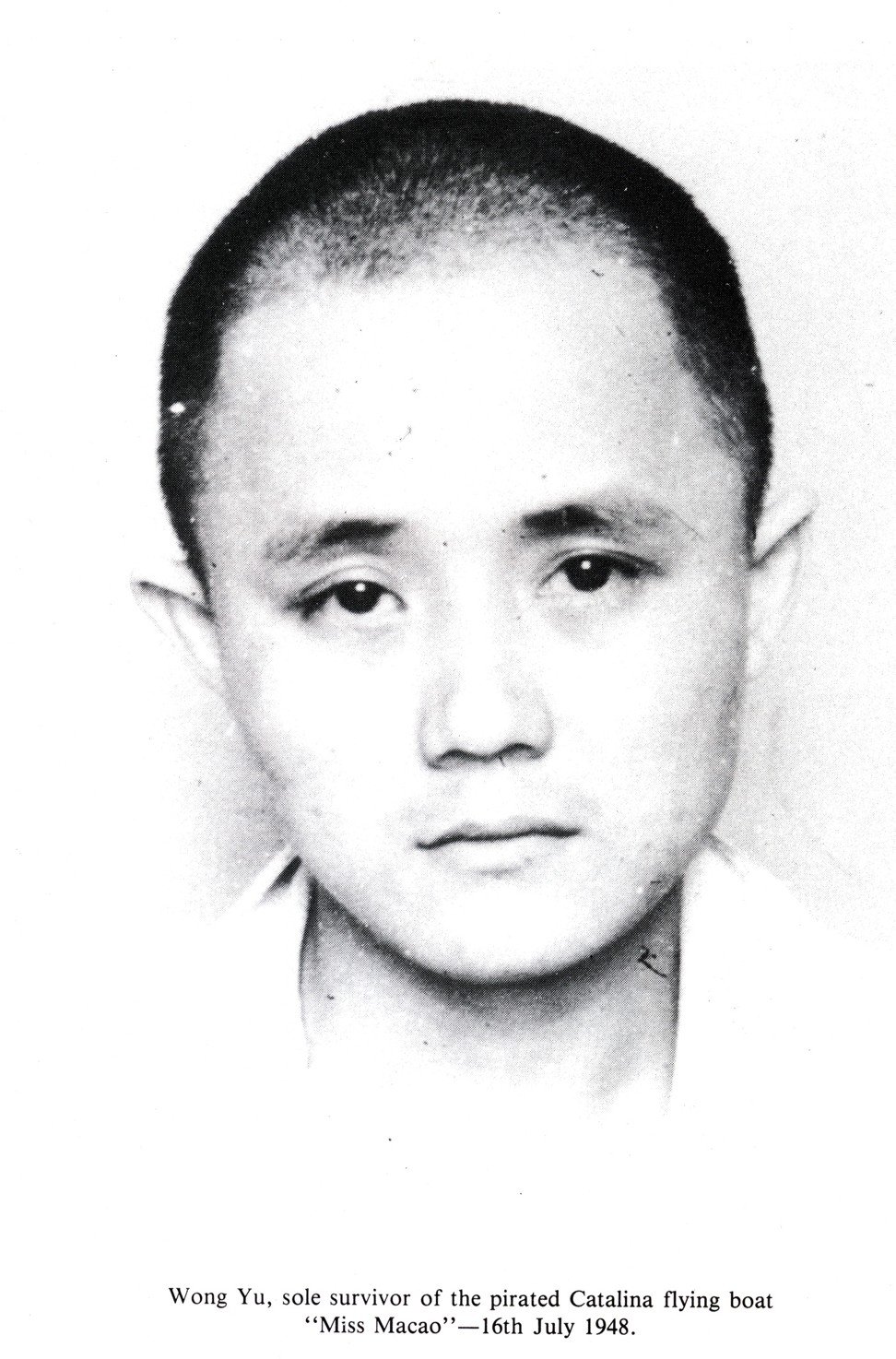

A clearer picture emerged when police disguised as patients entered Wong’s hospital room and recorded a confession. According to Wong, the bandit Tai Wong-yee had been behind the plot and four gang members, including Wong, had been on the plane.

“The four gunmen pointed their guns at passengers and members of the crew very shortly after the Catalina’s departure from Macao,” the Post reported on August 16. A scuffle had broken out, shots had been fired, and when the pilot was fatally wounded, control of the plane had been lost.

“Wong Yu possibly owed his escape to his position near the exit of the plane and climbed out before the crash,” it concluded.

On September 9, 1949, the Post reported that the Hong Kong government had concluded no admissible evidence existed that would permit a trial of Wong to be tried Yu in Hong Kong. No application for extradition from Macao would be made.

On June 12, 1950, the Post reported that Wong had been released without charge after two years in detention.