Bend the knee to a royal? I’m lucky I don’t have to – though the Singaporeans that came before me did so more than once in their lifetimes

- Although not the case any longer, many Singaporeans of a certain age had to swear allegiance to a ruling monarch – for some, to several in their lifetimes

- Before its independence, Singaporeans were subjects of Malaysia’s king. Before that, it was occupied by Japan – and before that, they were ruled by UK royalty

For anti-monarchists, the past week must have been excruciating as they watched people fawning and simpering over a privileged group of grandees in fancy dress. I am referring, of course, to the coronation of the British king, Charles III, and the expensive pantomime paid for by British taxpayers.

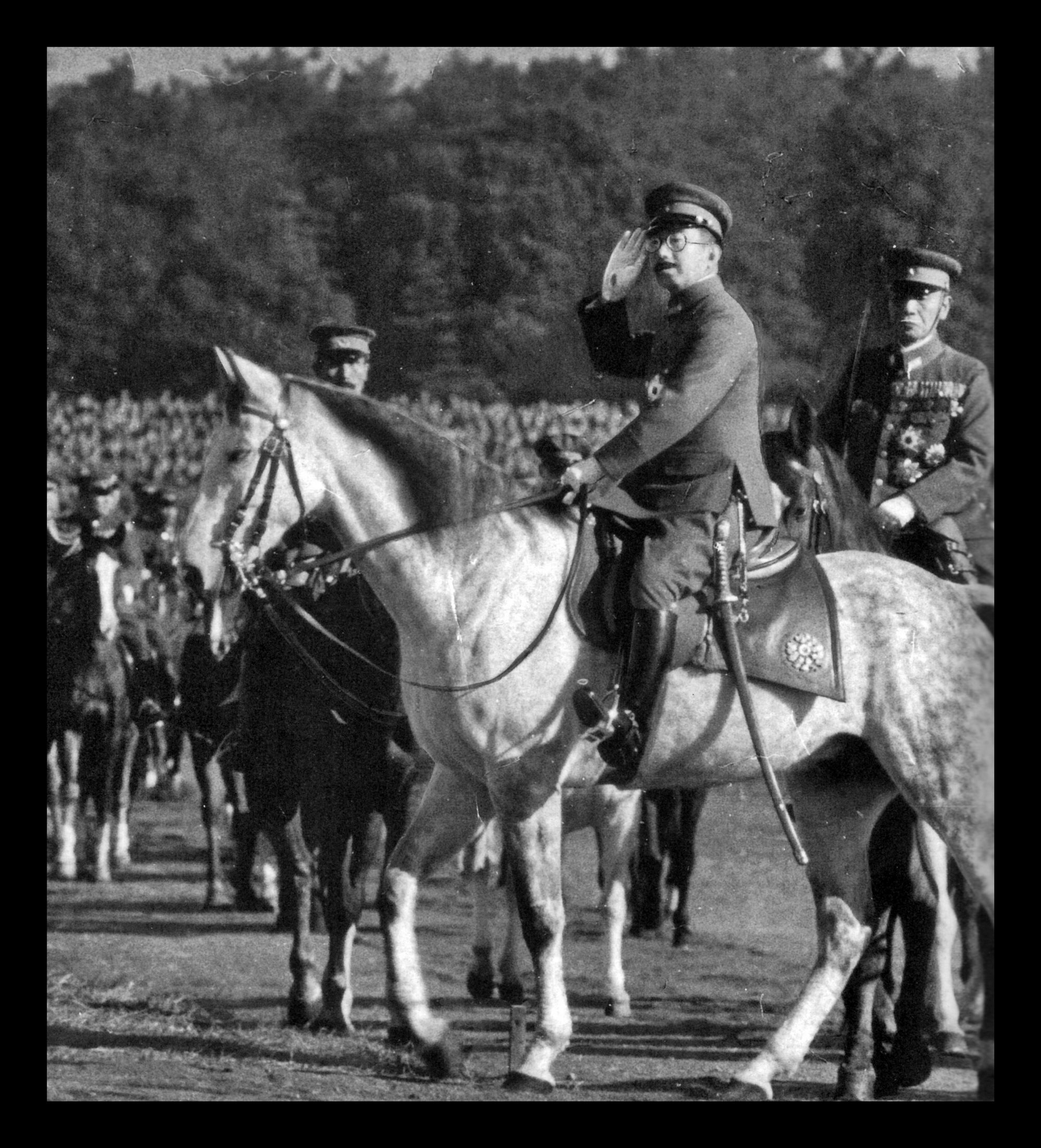

But they are a link to our past, you say. The British royal family boasts a 1,000-year bloodline. The Japanese emperor, for those who believe in fairy tales, is a direct descendant of the sun goddess.

We are all descendants of bloodlines that stretch back to the earliest humans, except our ancestors did not enrich themselves by waging war, plundering and slave trading. Or perhaps they did, but we are in the furthest fringes of the family tree to reap the fruits of that now.

I am lucky that I have not had to bend the knee before a crowned head of state. I have sworn allegiance maybe once to a president who occupied his office by virtue of his own accomplishments, not his birthright.

My parents, in contrast, were subjects, at least nominally, to four monarchs in their lifetimes – though, if you ask them now, they would probably say they were too young to remember or too busy to care.

Japan surrendered in 1945 and the British returned to Singapore. George VI was still on the throne in London, but the mood in Malaya had changed. Britain’s defeat in Southeast Asia broke the myth of European supremacy and the erstwhile “natural order” of the “white right to rule”.

In 1946, Singapore was formally separated from its Malay Peninsula hinterland, the first time in its 700-year history, as a separate crown colony. George VI died in 1952 and his daughter Elizabeth II succeeded him as queen. My 12-year-old parents might have watched her coronation on television in 1953, but they do not remember.

My parents, by then in their early 20s, became subjects of Tuanku Syed Putra, Malaysia’s yang-di pertuan agong, or king, at the time.

After two short, turbulent years in Malaysia, Singapore was out on its own as an independent country in 1965. Although the descendants of local Malay royalty were still living in Singapore, the fledgling nation chose to become a republic with a president as its ceremonial head of state.

My parents married a year later. The government office where they solemnised their marriage would have had on its wall the photograph of Yusof Ishak, accomplished journalist, former chairman of the Public Service Commission, and the first president of Singapore.