How official Chinese propaganda is adapting to the social media age as disaffection spreads among millennials

- Communist Party’s official outlets scouring country for new media specialists to reach 800 million web users and squeeze out ‘undesirable influences’

- Growing disaffection among younger generations prompts party outlets to cut back on Communist jargon in effort to ‘reach people’s hearts’

China’s leadership has started a propaganda blitz amid concerns about rising dissent among younger internet users.

Observers said Beijing was seriously concerned that online media was having an “undesirable influence” on young Chinese people and was trying to ensure they got more exposure to the officially approved narrative.

At the core of this drive is a team of millennial new media specialists who eschew the jargon-heavy style of traditional propaganda in favour of stories designed to resonate with younger, web-savvy citizens.

China directs news sites, app developers to promote ‘positive energy’ online

President Xi Jinping told a January 22 meeting of senior officials that they should regard the political risk from public dissent as their top priority and prepare for the “worst-case scenario”.

The Chinese leadership is acutely sensitive to the danger of public dissent as the economy starts to slow, and recent months have seen protests by army veterans, teachers and young Marxist students supporting workers’ rights.

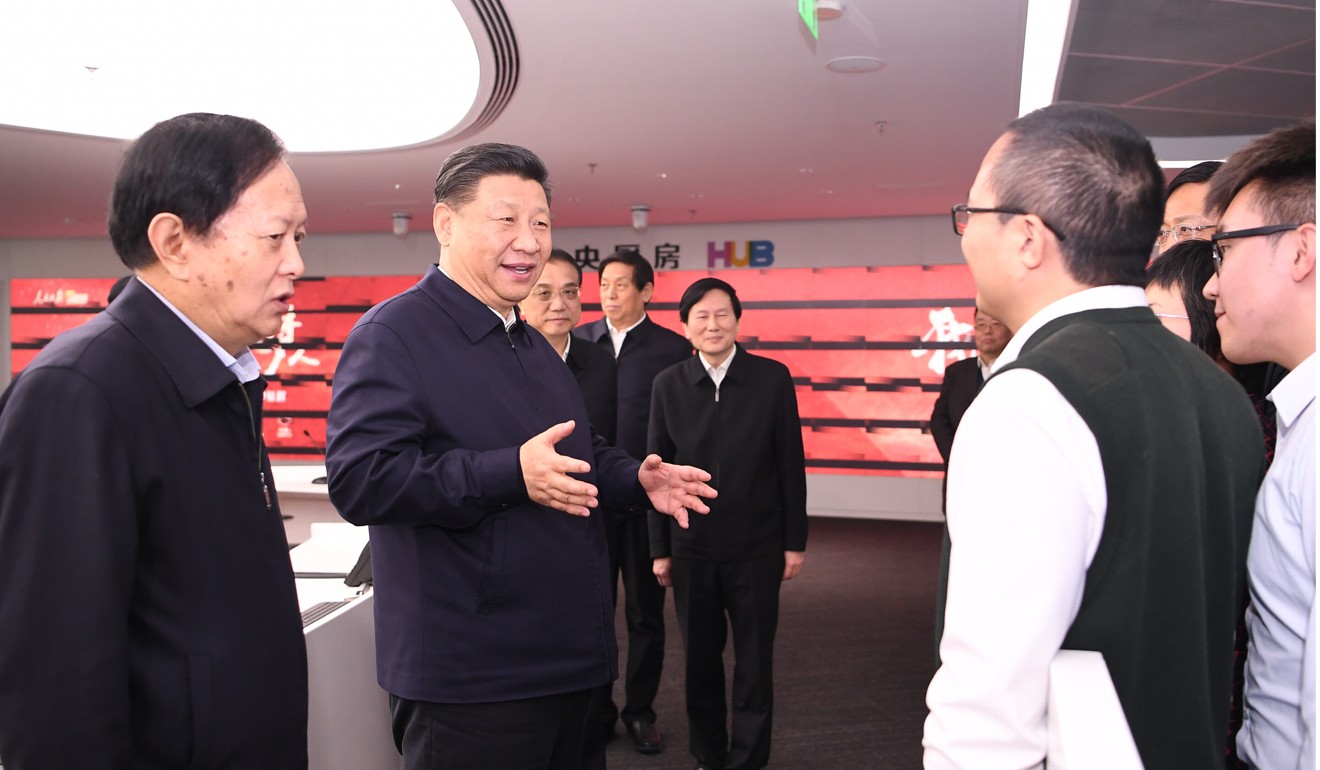

Four days after his speech, Xi led members of the political bureau of the Communist Party Central Committee on a visit to the new media operation of People’s Daily, the party’s mouthpiece.

He spoke at length on the importance of “boosting integrated media development and amplifying the mainstream voice” in public communication.

China rips into Tencent’s news service, killing 9,300 mobile apps

“Mobile platforms are the priority,” Xi said, adding that he wanted his propaganda chiefs to put in serious efforts to “develop websites, Weibo, WeChat, electronic newspaper bulletins, mobile newspapers, IPTV and other forms of new media”.

Some senior officials have already heeded his call with Yu Weiguo, the party chief for Fujian province, visiting the local bureau of People’s Daily three days after Xi’s comments to drive home the message.

Mobile platforms are the priority

The Chinese internet has always been heavily censored but the new focus on Xi’s demand to ensure “the voice of the party can reach all kinds of user terminals directly”, has prompted propaganda chiefs to hunt down new media specialists from all over the nation.

They have been recruited to provide platforms for the party’s official mouthpieces and promote what is described as “positive energy” among the nation’s 800 million web users.

Deng Yuwen, an independent scholar at the China Strategic Analysis Centre, said: “Xi listed political risk as the top priority [at the study session]. The fact that he immediately followed up with the trip to People’s Daily to talk about new media, shows that he believes controlling the new media’s influence on Chinese youth is key to mitigating the risk.”

On January 18, Public Security Minister Zhao Kezhi warned of the risks of a “colour revolution” – a reference to the range of protests that swept a number of former Soviet countries a decade ago – and asked all law enforcement forces to “resolutely defend political security”.

China’s cyber police take aim at ‘negative information’ in new crackdown

After 40 years of rapid growth, China’s younger generation now feel they have fewer opportunities to move upwards, while facing a lot more pressure in work and life.

The growing disaffection that resulted has alarmed the party leadership and prompted a debate about what some academics characterise as “intergenerational inequality” as younger Chinese people lose out on the benefits enjoyed by the generation who grew up at the peak of the country’s economic boom.

One consequence is that a demotivational slacker culture known as “Sung” has become popular online among people born in the 1980s or 1990s.

A study by the China UC Big Data Centre said the phenomenon was driven by a sense of alienation caused by factors such as skyrocketing home prices, a lack of social mobility and the difficulty of finding a partner in modern China.

Chinese social media stunned as nearly 10,000 accounts shut down

These social divisions are exacerbated by social media, where many affluent millennials enjoy showing off their wealth online.

One popular meme last year was the “flaunt your wealth” challenge, where people posted photographs showing themselves sprawled on the ground surrounded by valuables as if they had tripped and dropped them.

Unsurprisingly, the party’s renewed focus on social media includes vigorous efforts to counteract this trend.

One part of the crackdown has targeted popular social media accounts that are accused of sensationalising social problems or failing to police their content properly.

Last month, a popular WeChat account called Mimeng, which was known for its use of clickbait headlines, was denounced by official media outlets for publishing a story about a bright young man who died in poverty despite his hard work and determination to improve his lot in life.

Onions kill the flu virus? Not true, say WeChat’s fake news debunkers

The story was widely spread online before many elements of it were debunked, prompting a denunciation by People’s Daily that attacked those spreading “poisonous” stories online.

The publisher was forced to apologise and close her Weibo account. She also promised to suspend her WeChat operations for two months for “profound self-reflection”.

Another leading voice in the backlash against “irresponsible” social media users “cashing in on people’s anxiety” is the official WeChat account of the Central Political and Legal Affairs Commission.

This lies at the heart of the party’s efforts to control the social media narrative and operated for three years under the nickname of Chang An Jian – or Sword of Long-lasting Security – complete with anime-style avatar, before disclosing its true identity in November.

The South China Morning Post understands that this new media operation is run by a small central team of fewer than 10 people, all of whom were born in the 1980s or 1990s.

Tencent tightens control of WeChat content amid crackdown

The selection process for this core team, and the provincial operations working under them, is stringent and includes screening candidates for political loyalty.

They also need a background in law enforcement – whether in the police, courts, justice department or prosecutors’ offices – must be familiar with new media platforms such as WeChat or Weibo and, of course, be willing to work the very long hours more common in internet start-ups than government jobs.

Those who make the grade will be sent to Beijing for six months of intensive training before returning home to lead provincial and municipal new media teams.

A source said the process helped the new media centre to “keep the team fresh with the best people from all over China”.

After their training finished they could “bring back the experience gained in Beijing, so we can build stronger provincial teams”.

Unlike the traditional top-down structure of propaganda departments, the new media team had more editorial freedom “not necessarily following orders from the top”. When deciding what stories to promote, “the first consideration is can we reach people’s hearts?” the person said.

When they cannot reach a consensus on what message to promote, the team takes a vote and even the boss can be overruled.

Xi to shake up propaganda, cyber chiefs as overseas image suffers

Deng said that while traditional official media was targeted at party cadres, new media operations had to reach a wider audience, so they “have to adapt to a more reader-friendly format and use less party jargon in their reporting”. He also said they had achieved a “certain success” in this up to now.

Official new media platforms have an inbuilt advantage when it comes to growing their audiences as all provincial and municipal law enforcement agencies make it compulsory for their employees to follow or “like” these new media accounts.

The Post has seen an official document from the Political and Legal Affairs Commission in Siping, a city in Jilin province, in which Politburo member Guo Shengkun tells all Chinese police officers to subscribe to the new media accounts operated by the Central Political and Legal Affairs Commission, which he heads.

[New media operations] have to adapt to a more reader-friendly format and use less party jargon

China does not publish official figures for how many police officers it has, but Fan Peng, a researcher at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, estimated the number at about 1.6 million in 2014.

According to Leibei.com, which tracks WeChat public accounts, Chang An Jian has about 670,000 active subscribers and its Weibo account has more than 6 million followers.

Another official media account operated by People’s Daily, Xia Ke Dao – or Swordsman of the Island – has more than 1 million active followers.

Some analysts believe the growth of these official accounts will squeeze out other new media players as official media has a monopoly on hard news reporting.

Chinese state broadcaster registers with US as foreign agent

Alfred Wu, an associate professor at Singapore’s Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, said: “The space for non-official new media players will shrink further under the current atmosphere.

“All the policy, current affairs-related reporting is monopolised by the official channels, others can only write soft content such as relationships, the zodiac etc.”

But Henry Chan, a visiting senior research fellow at the Cambodian Institute of Cooperation and Peace, said that in other areas China’s official media had been lagging behind for years.

The crux of the problem was “not the format or the platforms”, but their content, he said.

“Overstressing ideology makes them lack the most important quality of modern media, responding quickly [to breaking news].”