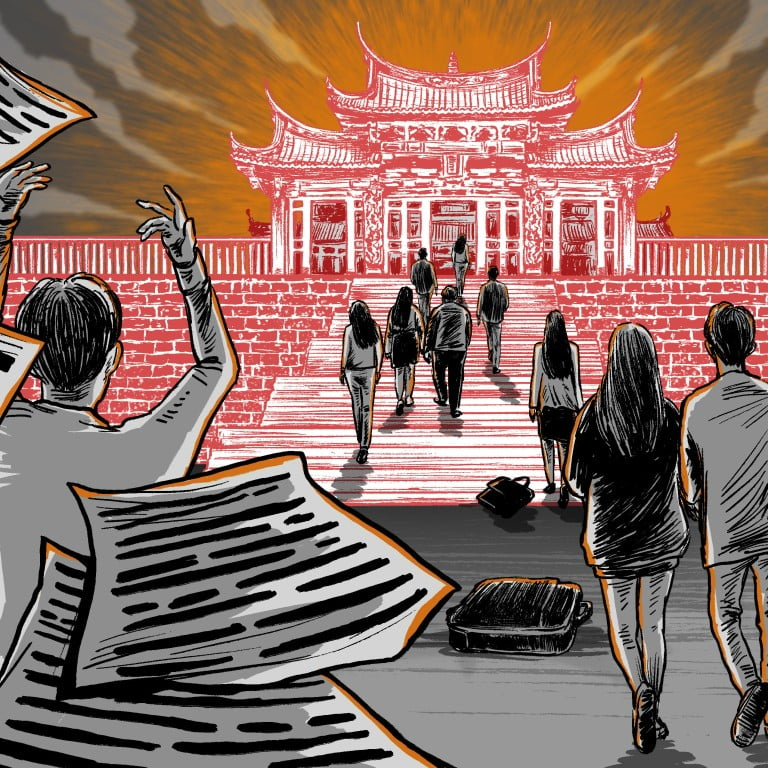

Anxious and stressed about their careers, young Chinese are flocking to temples

- More are seeking to escape from pressure and pray for good fortune, while some soak up ‘temple life’ as volunteers for months

- Buddhism and Taoism are part of traditional culture, and now their temples are ‘a key pillar of tourism’, religious affairs expert says

Like many of her peers, Lu was ambitious and spent her university years planning for her career – with a degree in Chinese, she saw a future in e-commerce. But 12 months into her first job she needed a break and decided to volunteer at the temple in Jiaxing, Zhejiang province.

Lu is among a growing number of young graduates who, feeling disillusioned or burnt out, have temporarily retreated from the highly competitive job market to rethink their path.

“The pandemic has upended not only the economy but also many of our assumptions about life,” said Lu, who is now 25 and plans to spend a year at the temple.

“The economic downturn and rising unemployment has caused great anxiety among many people my age. With all the uncertainties, many are choosing to hold onto secure and stable jobs. But there’s also some who are like me in wanting to pause and rethink what I truly want in life.”

China’s economy has started showing signs of recovery in recent months as the country emerges from three years of stringent Covid-19 controls. But the youth unemployment rate hit 17.5 per cent last year, rising further to 18.1 per cent in the first two months of 2023.

Young people aged 16 to 24 have often been hit hardest by job losses during the pandemic. In the US, youth unemployment rose to 27.4 per cent in April 2020 before dropping to below 9 per cent last year.

Chinese experts have raised concerns that the lack of job opportunities for young people could have an adverse effect on the outlook for the nation’s economic development.

China’s ‘employment-first strategy’ is under way, but can it create enough jobs?

As China has reopened and dropped its tough Covid-19 rules, Buddhist and Taoist temples have in recent months become a popular destination for young Chinese like Lu seeking to escape from life’s pressures and pray for good fortune.

Visits to temples across the country have surged 310 per cent since the start of 2023 from a year ago, with Millennials and Gen Zers accounting for half of those bookings, according to data from online travel service provider Trip.com.

Temples previously only saw big crowds during major festivals and holidays, but that is changing fast. Temple-hopping has become a trendy activity for young people who are not looking to become monks or nuns but want to reduce their work and life pressures through a Buddhist or Taoist lifestyle.

For many young temple-goers it is a weekend excursion. Others, like Lu, stay for months as volunteers, receiving spiritual and emotional support while helping out with daily chores and attending lectures.

The Lama Temple, or Yonghe Palace, in Beijing – a Tibetan Buddhist temple – is among the most visited. Part of it was an imperial palace where two Qing dynasty emperors lived while they were heirs to the throne, and it is known as a temple for worshippers to take career development wishes.

That has made it popular among young Chinese. In recent months long queues of visitors have regularly been seen outside the temple – even on weekdays. About 40,000 people have visited per day since early March, according to the temple.

These visits often include a stop at its souvenir shops, where visitors have been spending an average of 200 yuan to 1,000 yuan (US$29 to US$145) buying “blessed objects” like bead bracelets for good fortune, according to posts on social media.

Such is the demand for temple souvenirs that they are also being resold online on shopping platforms such as Taobao – run by Alibaba Group, which owns the South China Morning Post – and Xiaohongshu, a popular Instagram-like lifestyle app.

Practices such as incense burning and chanting have also emerged in app form. Multiple apps are available for “digital wooden fish” – named after a percussion instrument made from a hollow wooden block that is used to beat a rhythm when chanting scriptures in Chan Buddhism, a Chinese Buddhist sect. One version on the Huawei app store has been downloaded over 5.7 million times, with many users saying they find it helpful when they are stressed.

The phenomenon of young Chinese – most of whom have had an atheist, Marxist education – flocking to temples has also drawn attention in state media.

A recent commentary in The Beijing News declared that “some young people have taken the wrong path in handling pressure”. The official newspaper urged young Chinese to work hard rather than pinning their hopes on “lighting up incense”.

How intoxicating sandalwood captivated a continent: a 3,000-year history

Tian Wenzhi, a commentator with state-run Beijing Daily, took a more sympathetic view last month, saying the focus should be on trying to understand the pressures faced by young people and what it is they are searching for.

“A fast-paced life full of uncertainties in today’s society has created greater challenges and anxieties among young people who are worried about their career and marriage choices as well as the pressure of taking care of the older members of their families,” he wrote, referring to the difficulties many single-child families face.

For Chinese people, it’s more about turning to whichever god is perceived to be more useful to them

Fan Zhihui, an expert in philosophy and religious affairs at Shanghai Normal University, said Chinese people had long taken a more pragmatic and utilitarian attitude towards religion – in contrast to the more organised and monotheistic tradition in Western religions.

“Buddhism and Taoism have been a part of China’s traditional culture and now Buddhist and Taoist temples are a key pillar of domestic tourism,” Fan said. “Some young people might be curious about these religions but it’s not the same as the much stricter adherence to religious teachings and practices seen in Christian churches in the West.

“For Chinese people, it’s more about turning to whichever god is perceived to be more useful to them as they navigate life’s challenges.”

The new-found interest in temple life is clear to see on Chinese social media. On the Xiaohongshu lifestyle app alone there are currently close to 900,000 posts on the subject, with people sharing their experiences of temple visits and seeking information.

Another recent graduate, 23-year-old Yao Fenfen, said she decided to spend a few days at a temple in Shenzhen after reading about it on the app.

“I was laid off earlier this year and wanted to make good use of this free time to experience more and relax a bit before I start a new job. I saw some posts on Xiaohongshu about volunteering at temples and thought this would be a cool experience,” she said.

“I made many new friends during the stay. Many of them are my age and also recently left their jobs – they also came to experience temple life after reading similar posts.”

Lu, the young graduate who has spent the past three months at a temple in Zhejiang, said the trend reflected a younger generation that is more willing and open to explore different lifestyles. Lu used to be a Christian but said she was no longer religious, though she was drawn to the Buddhist lifestyle and teachings that focus on inclusivity and kindness.

“Unlike my parents’ generation who were born at a time when poverty, famine and political turmoil was not a very distant memory, my generation no longer has to worry about these things,” she said. “We enjoy more space and freedom to think about issues like spiritual fulfilment and to choose a path according to our instincts instead of what society demands.”