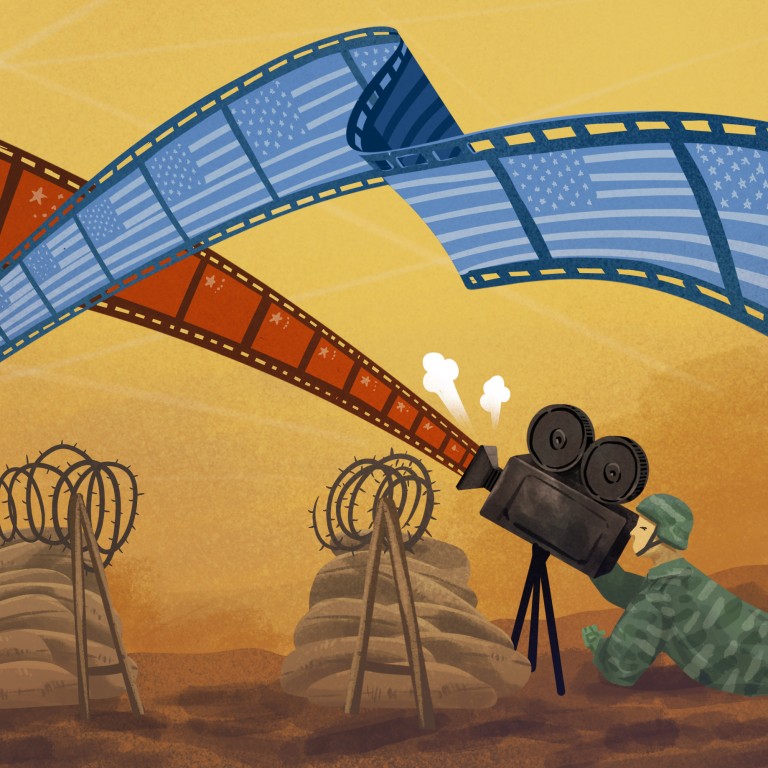

China mounts cultural offensive to win ‘war of narratives’ against US. Will other countries be swayed?

- Beijing aims to boost confidence in Chinese history and culture at home, while to the outside world it pushes respect for ‘diversity of civilisations’

- Analysts say the rhetoric resonates in some developing nations, but most want to avoid picking sides

Warner Bros Discovery executive Vikram Channa was there – as was Oscar-winning British documentary director Malcolm Clarke.

“China has been the subject of a lot of negative publicity in the West during the last 10 years,” Clarke said in a video for the workshop. “Part of what I’m trying to do is to counter that kind of negative publicity, not by necessarily telling happy, good stories about China, but just simply by telling the truth about what’s happening here.”

Earlier in June at a cultural symposium in Beijing, Chinese President Xi Jinping said China’s unique development path was rooted in the historical continuity of its culture. Since then, Xi’s vocal support for traditional Chinese culture – as shown by his recent visits to the National Archives of Publications and Culture and the Chinese Academy of History – has been echoed by state media.

The initiative calls for respecting the “diversity of civilisations” and opposes “stoking ideological confrontation” or imposing the values of one country onto another.

Xi unveiled the initiative in a keynote speech to the Communist Party High-Level Dialogue with World Political Parties in March, an event attended by leaders of about 500 political organisations from more than 150 countries.

At the dialogue, Xi called for respecting the diversity of civilisations, advocating common values, valuing the history and innovations of different cultures and strengthening people-to-people exchanges and cooperation.

“The practice of stoking division and confrontation in the name of democracy is in itself a violation of the spirit of democracy,” he told the audience. “It will not receive any support.”

George Magnus, a research associate at Oxford University’s China Centre said it was “probably no accident” that the two meetings took place back to back.

“The important question is whether Xi’s framing of the GCI is fundamentally any different from Biden’s framing of the struggle of democracies and autocracies,” Magnus said.

“I think that what we have is a clash of ideologies, not cultures, which ultimately comes down to differences in the ways we perceive rights, beliefs, standards and values.

“Xi’s China and liberal leaning democracies may speak to a common agenda of peace, development, equity, justice, democracy and freedom, but he uses Marxism and ancient Chinese culture to define a very different version of what these mean from the alternative based on rights, and the rule of law.”

According to Magnus, the stark contrast in the narratives is designed to cement bonds with a disparate group of nations with differing political systems and goals.

He said that while Xi probably had little chance of swaying developed market economies to his side, there were hopes that many countries in the Global South – encompassing most of the world outside North America, Europe and a few rich Asia-Pacific nations – could be persuaded.

A mainland-based political analyst, who requested anonymity due to the sensitivity of the matter, said the Communist Party launched the GCI to counter the “cultural hegemony” of the West.

“The party thinks that the China model of development and modernisation is downplayed and even criticised in the Western-dominated narrative. What Beijing wants to do is to make its voice heard, make the Chinese wisdom a public product for the world and fight back against Western cultural hegemony,” the analyst said.

“The rhetoric of appreciating perceptions of values by different civilisations has some appeal to developing countries, which are desperate for funds, technology and know-how from China or share China’s disdain for Western values.”

Why China’s C-pop has yet to score as a soft power music machine

Liu Zhenmin, a Chinese diplomat who was undersecretary-general for the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs from 2017 to 2022, said the GCI, together with China’s Global Development Initiative and Global Security Initiative, reflected Xi’s world view of a “shared destiny for mankind”.

“[This world view] is to break the values-based Western diplomacy, stop suppression by Western countries under the name of democracy and unite countries around the world,” Liu told a GCI symposium in March hosted by the Study Times, the newspaper of the Central Party School in Beijing.

Under the security initiative, unveiled last year, China says it wants to show the world that it seeks peace and development. As part of the framework, Beijing has come up with a proposal to end the war in Ukraine and brokered a truce between Iran and Saudi Arabia.

Beijing’s efforts in general do seem to be gaining it some favour.

In a report released in October, University of Cambridge researchers found that 62 per cent of citizens in developing countries viewed China favourably, which rose to 70 per cent among those who did not live in liberal democracies.

And for the first time since the data was first collected in 2011, slightly more people in developing countries (62 per cent) were favourable towards China than towards the United States (61 per cent).

According to the study, which combined data from 30 surveys covering 137 countries, developing nations with high levels of trade and investment with Beijing – especially members of the Belt and Road Initiative – had the most favourable view of China.

Early last year China formed a group in the United Nations called the “Friends of the Global Development Initiative”, with 53 member states. Now it has nearly 70, as China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs revealed last month.

While China is making some progress in its bid to build a multipolar world, especially in the Global South, few countries will go all in on Beijing, as it remains in their best interests to hedge between the rival superpowers and avoid picking sides, according to analysts.

“Quite a few countries tilt towards China only for short-term interests, as Western cultures and values have a bigger sway after a long period of colonisation or because Western countries have economic or market supremacy,” the anonymous analyst said.

China’s Xi hails cultural continuity for powering nation’s rise

Sourabh Gupta, a senior fellow at the Institute for China-America Studies in Washington, said China intended to “soften the ground” for its rise – and acceptance of that rise – within the international system.

“The aim seemingly here is to suggest that China’s rise will not follow the beaten path of the Western powers, and that Beijing cherishes and advocates for the diversity of world civilisations. It is not so much an anti-Western message as it is a non-Western message to those interested in lending an ear,” Gupta said.

“The GCI narrative will not sway countries markedly one way or the other. The civilisational dialogue theme is a tried-and-tested one and runs up against a certain [low] ceiling in terms of its resonance.”

Gupta said that when it came to stoking cultural pride among Chinese people, Xi was preaching to the choir, but “for the great mass of the non-converted beyond China’s borders, they will stay that way”.

Noting Beijing should do more to explain the GCI to those outside China, he said: “Westerners have neither the curiosity nor the inclination to parse these highly conceptual utterances, especially beyond economic policy measures, and I doubt they will provide a platform for engagement and contestation in a ‘narrative war’.”

Pang Zhongying, a professor of international affairs at Sichuan University, said the initiative needed to be well defined.

“What does ‘global civilisation’ mean? If it refers to a new civilisation that unites countries regardless of ethnicity and nationality to address global crises and challenges such as climate change, it would be a good initiative,” Pang said.

“So far, the initiative is still ambiguous with empty slogans.”