What you need to know about Chang’e 4, China’s mission to the far side of the moon

- From the myths that inspired the name of the Chang’e landing to the future of space exploration, we take a look at some of the most interesting aspects of this mission

China’s Chang’e 4 mission, which successfully touched down on Thursday, is the first time a probe has successfully landed on the so-called dark side of the moon.

The US, EU, Japan and India are also looking at moon missions in future years, but the Chang’e mission has already sent two satellites and another unmanned rover to Earth’s nearest neighbour.

The latest programme is the most ambitious yet and is designed to explore this hitherto unexamined part of the moon.

What is the origin of the name and why did China chose it for its lunar programme

The goddess Chang’e (the first syllable is pronounced chahng while the “e” is a long e, as in “her”) is the subject of several tales from Chinese mythology and folklore and lives on the moon with her pet Yutu, which means Jade Rabbit.

The moon goddess is also a central character in the annual Mid-Autumn Festival, where her husband, Houyi, is believed to prepare cakes and fruits to commemorate her on that day.

There are different stories about how Chang’e came to fly to the moon after drinking the elixir of immortality.

One popular version says she were forced to drink the elixir so it would not end up in the hands of a villain.

China’s Chang’e 4 lunar probe sends first photo of far side of the moon after historic soft landing

In this version, there were 10 suns in the sky thousands of years ago. Houyi, an excellent archer with the strength of Hercules, shot down nine suns and left one in the sky, saving people from the intense heat, and the gods rewarded him by giving him an elixir of immortality.

He gave it to Chang’e and told her to put it aside for he did not want to live forever without his wife.

But Houyi’s evil apprentice, Fengmeng, heard the news and broke into the house when Houyi was not at home.

Chang’e had to drink it herself to prevent Fengmeng from obtaining immortality, and instantly flew into the sky, taking her rabbit with her. That night there was a full moon in the sky so she flew there directly.

During the Apollo 11 mission, Nasa headquarters told the astronauts the story as they were orbiting the moon, urging them to look out for a “lovely girl with a big rabbit”.

How tiny satellites are helping China in the space race

Michael Collins, who remained on board the orbiter throughout the mission, replied saying: “OK. We’ll keep a close eye out for the bunny girl.”

Where does Queqiao, the name of the relay satellite, come from?

Queqiao, which roughly translates as “magpie bridge”, is where two lovers who have been separated from each other in space meet once a year, according to Chinese folklore.

This story tells of the Cowherd a poor young man who met and fell in love with the Weaver, a fairy visiting the world.

But the gods were upset by their marriage and punished the lovers by separating them for each other for all eternity by stranding them on opposite sides of the Milky Way. However, they are allowed to meet once a year – on the seventh day of the seventh lunar month when thousands of magpies form a lunar bridge to cross the Milky Way and meet in the middle.

The use of the name of the relay satellite highlights the logistical challenge of landing a rover on the far side of the moon because it cannot communicate directly with Earth. The Queqiao relay satellite was launched in May this year to solve this problem.

Operating about 400,000km (250,000 miles) from Earth, Queqiao will transmit Earth’s signals to and from the lunar lander and rover.

2019 China science look-ahead: from moon landing to an AI arms race, four things to expect in the year ahead

Dark side of the moon or far side of the moon?

Technically, the far side is more accurate because it is still exposed to the sun, but cannot be seen from the Earth.

This is because the moon orbits the Earth once every 27 days – the same amount of time it takes to rotate once on its own axis.

This is phenomenon, which astronomers call synchronous rotation, is the result of tidal rotation that slows the rotation of the smaller sphere until it remains in sync with the larger one.

It means that no human eyes ever saw what was on the far side until 1959, when a Soviet satellite sent the first images back to Earth.

What is a soft-landing?

A soft-landing means that rather than crashing onto the surface of a celestial body – a hard landing – a spacecraft lands on the surface of a celestial body, under guidance and monitoring by a control centre back on Earth.

In 1966, the Soviet Union’s Luna 9 was the first spacecraft to soft-land on the moon. Soft-landing keeps the craft intact and allows it to perform operations as well as deploying other devices, such as a rover.

Landing on the moon properly is the rocket-science equivalent of a stuck landing in gymnastics. The Soviet Union failed twice with Luna 7 and Luna 8 before succeeding with Luna 9.

China achieved its first soft-landing on the moon in 2013, with Chang’e 3’s lander and rover. This happened four years after its first hard-landing when Chang’e 1 crashed on the moon as designed.

What is a lunar rover and which countries have sent such spacecraft?

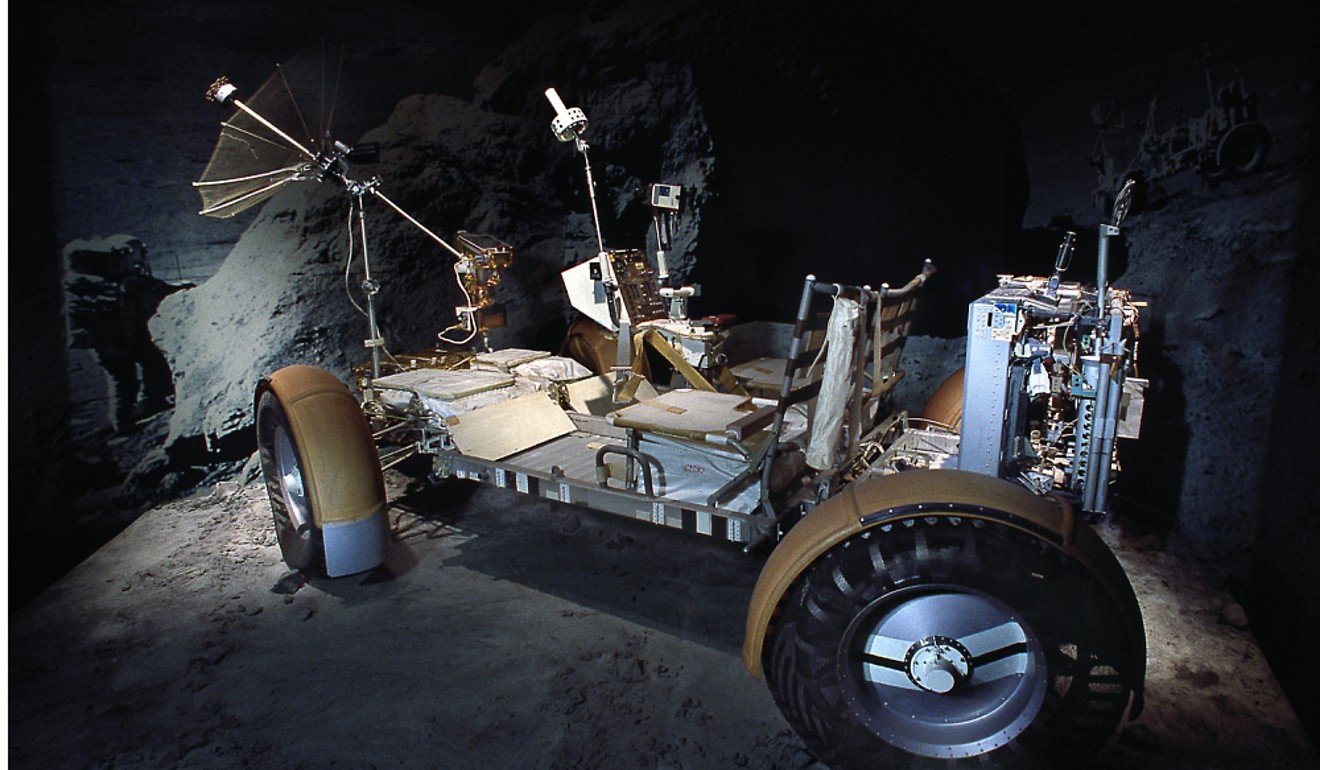

Lunar rovers are battery-powered “dune buggies” taken to the moon aboard a landing vehicle. They are stowed on the lander and deployed upon arrival.

The first rover to land on the moon successfully was the USSR’s Lunokhod 1 in 1970, after an initial attempt to send a vehicle failed in the previous year.

Nasa’s Apollo missions 15, 16, and 17 brought more lunar rovers on the moon in 1971 and 1972 – the only vehicles to have been driven by humans on the surface of the moon.

China successfully landed its first lunar rover, Yutu during the Chang’e 3 mission in 2013. However, the rover stopped moving due to a mechanical problem about 40 days after its landing. It continued to send images and data about the lunar surface back to the Earth until August 2016.

From moon landing to AI, the year ahead in Chinese science

What is the bigger picture?

The appetite for lunar exploration seemed to fade in the 1990s, after Japan’s first moon orbiter, Hagoromo, lost contact with its control centre.

It was the first attempt to send a lunar orbiter into space by a country other than America or the former Soviet Union.

But in 2004, China’s government decided it should begin its own programme.

“There had been debates over whether China should spend time and money exploring the moon,” Ouyang Ziyuan, chief scientist of China’s Lunar and Deep Space Exploration, said in an interview with state broadcaster CCTV.

“The State Council nodded through our plan in 2004 after we spent 10 years studying and polishing the proposal.”

Photos reveal origin of space rock Ultima Thule, resembling red snowman

Starting with the launch of Chang’e 1 in 2007, China’s lunar exploration plan has three phases: orbiting the moon, landing and exploration, and landing and returning to Earth with lunar samples.

What next?

China is near the end of the second phase: landing and exploration. The next mission, Chang’e 5, aims to launch a spacecraft that will land on the moon, collect samples and return to Earth with them by 2020.