‘We should be prepared’: bioethicists look at how to care for China’s gene-edited babies

- They say gene-editing technology is evolving and ethical issues should be considered

- Prominent bioethicists have called on the government to protect the three children

Chinese bioethicists are looking at the issues around caring for the world’s first gene-edited babies, and say more needs to be done to regulate research in the area.

Lei, a bioethicist at Huazhong University of Science and Technology in Wuhan, told a webinar last week that CRISPR techniques “evolve every day”.

“It is a very important and fundamental ethical issue – how to treat these people whose genes have been edited,” she said.

CRISPR is a technology that enables researchers to edit parts of the genome by removing, adding or altering sections of the DNA sequence. Scientists say it has the potential to cure a range of genetic diseases in the future, but for now that is still a long way off.

Qiu, who was also behind last month’s proposal submitted to the government, noted in an interview that the heritable genome editing technologies were still “immature”.

“Everything is still being explored. But based on the lessons learned from the He Jiankui case, we should consider these ethical issues in advance and be prepared,” said Qiu, a senior researcher at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences.

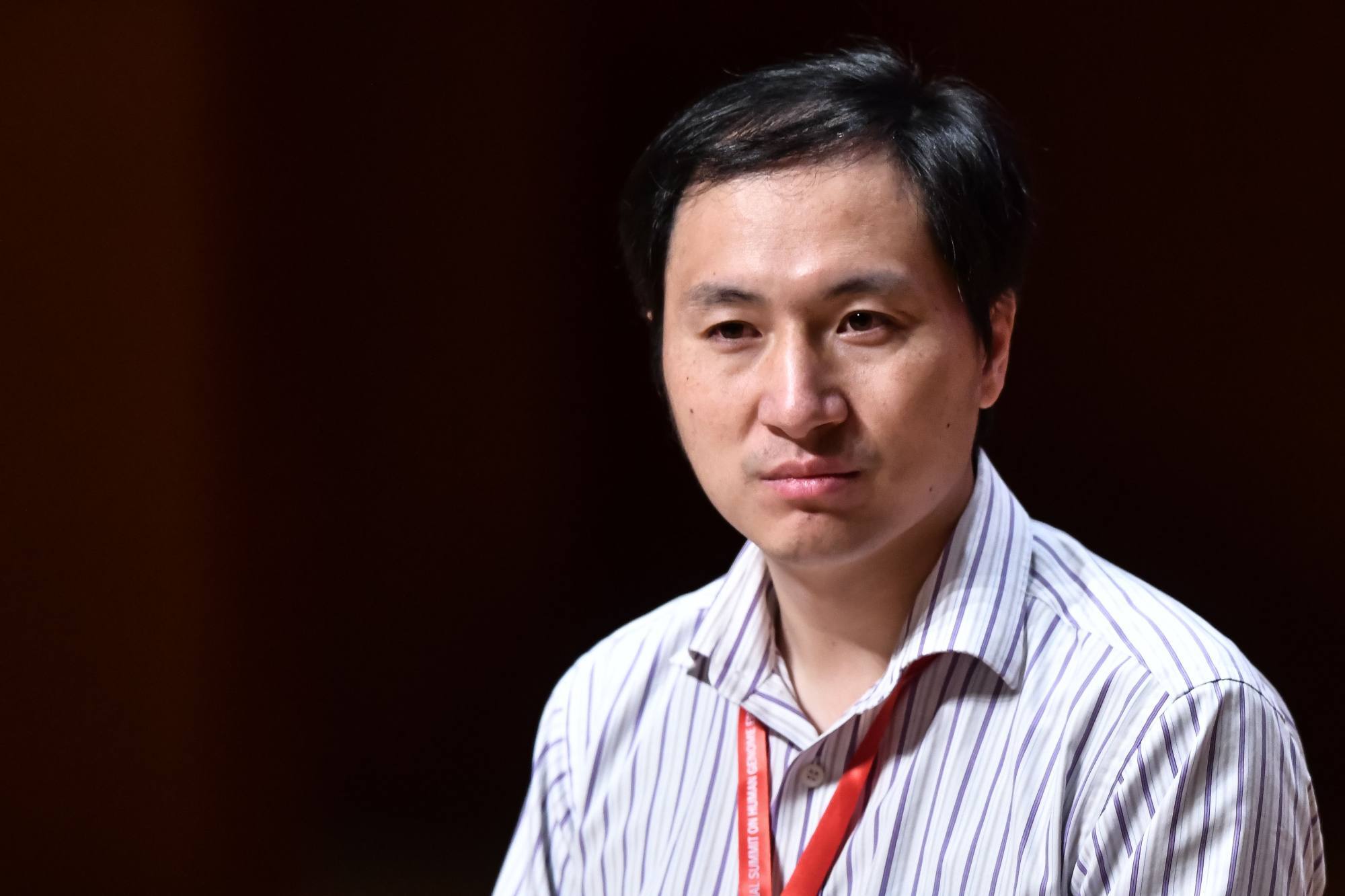

Scientist He stunned the world in November 2018 when he announced at a conference in Hong Kong the birth of twin girls with edited genomes, “Lulu” and “Nana”. A third gene-edited baby, “Amy”, was born later. The progress of the three girls is not known.

He said he had used the gene-editing tool CRISPR-Cas9 to rewrite the DNA in their embryos to make them less susceptible to HIV, which their father had. The experiment sparked an international backlash, with scientists saying the gene-editing technology was not ready to be used for reproductive purposes.

Speaking at the webinar on ethical issues around gene-editing, Lei said there was a scientific need for gene-editing, both in somatic cells, which are non-reproductive, and in the germline.

“Especially in the research of germline editing, we need to give ethical consideration and solutions as to how to regulate the research and how to treat people whose genes have been edited,” Lei told the webinar, attended by Chinese bioethicists including Qiu.

CRISPR has been used in hundreds of experiments all over the world, but all have involved somatic cells and aimed to treat diseases for which the DNA modifications are not heritable.

Eben Kirksey, a medical anthropologist at the Alfred Deakin Institute in Melbourne, Australia, said the research community had drawn a line between the use of CRISPR in adults that would not get passed on to future generations, and its use in the reproductive clinic.

“In the reproductive context, it’s very difficult to find a good use for this technology,” he said. “To my knowledge, there’s no clear use of CRISPR in the fertility treatment context that would be ethical.”

Kirksey said there were many effective therapies used to protect people from heritable diseases such as HIV, so genetically modifying children was not necessary. He said genetic “enhancements” – or the use of CRISPR to promote eugenics, or “good genes” – should be outlawed.

Gaetan Burgio, a geneticist at the Australian National University in Canberra, also said he could not see any clear medical indications requiring the use of human germline editing while other approaches were available.

Human germline editing is prohibited across the globe. A World Health Organization report released last year showed that out of 96 surveyed countries, 70 prohibited heritable human genome editing, and no country permitted it.

China tightened its regulation of human gene editing in the wake of the gene-edited babies scandal. Draft regulations released by the National Health Commission in 2019 require national-level approval for clinical research involving gene editing and other “high-risk biomedical technologies”. They also state that clinical research on new biomedical technologies has to go through academic and ethical reviews.

‘Foolish choice’: Chinese scientist’s gene-edited babies could die early

Although no country allows heritable human genome editing, Chinese bioethicists say there is a need to be prepared.

A year after He’s revelation, Russian biologist Denis Rebrikov told Nature he was editing genes in human eggs, aiming to alter a genetic mutation that can impair hearing, but did not plan to implant gene-edited embryos in women until he got regulatory approval.

“The technology is improving gradually and anyone with the technology can do it, though it may be illegal,” Qiu said, adding that some countries may allow it in the future.

“How should we treat these people? We should have policies on this issue.”

He said researchers needed to look at how best to protect the interests and well-being of the three gene-edited children in China.

According to Kirksey, the Chinese bioethics community is in a position to provide global leadership on the issue of gene-editing.

“If China offers ethical leadership, other countries will follow,” he said. “Clear rules for the road should be established.”