The knitter and the latecomer: 12 jurors who decided Patrick Ho’s fate in ex-Hong Kong minister’s US$2.9 million corruption trial

- Nine women and three men spent seven days in a New York courtroom before finding Ho guilty of seven of eight counts of bribery and money laundering

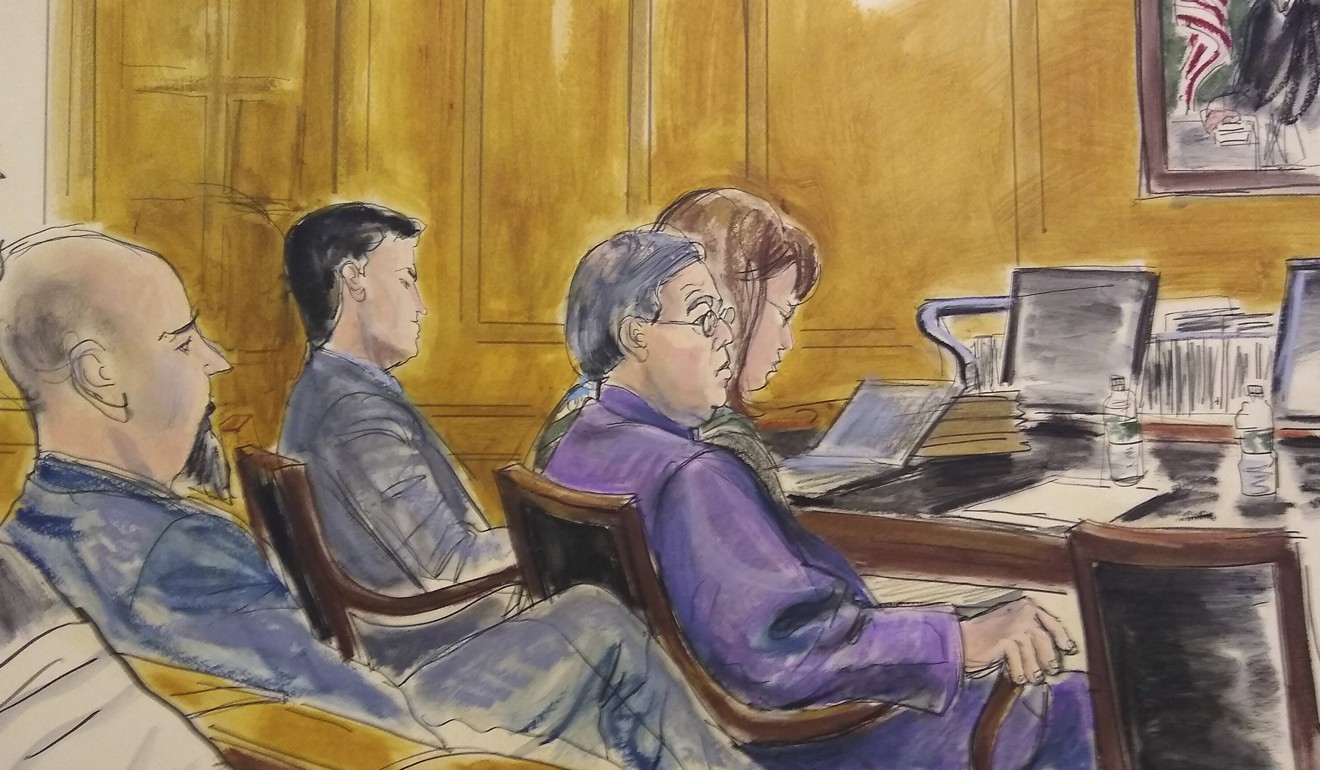

For seven days, nine women and three men have sat in a New York courtroom with former Hong Kong minister Patrick Ho Chi-ping, listening to the evidence pile up against him on bribery and money-laundering charges involving US$2.9 million.

The hand-picked jurors were there to weigh all that was presented to the Southern District Court of New York and decide Ho’s fate. On Wednesday, December 5, they decided he was guilty of seven of the eight counts he faced.

One juror, an older woman with grey hair and big reading glasses, brought her knitting to court and worked at it for five out seven days of the hearing, her needles set aside only on the first day, when she was selected, and the last day, when the lawyers presented their summations.

She appeared to stay engaged with the proceedings, however. From time to time she would raise her eyes from her knitting to the monitor in front of her to check whatever evidence was being presented by the lawyers. Then she returned to knitting again.

Almost every day, one woman juror arrived a few minutes late and held up the start of proceedings. On Day Two, one juror asked to keep a doctor’s appointment the next week, and another informed the court that his wife was due to undergo surgery the following week. No one took leave in the end.

Asked about the juror who was knitting throughout, former American criminal lawyer Robert Precht, who is now a founder of a legal think tank said: “I think knitting would be considered an automatic habit that would not distract a juror. If a juror were visibly asleep, that would be a more serious matter.”

As none of the lawyers present had objected to the woman’s knitting, he did not think it was likely to be considered improper.

Hong Kong Legal Exchange Foundation chairman Lawrence Ma Yan-kwok, also a barrister, said that in Hong Kong, jurors were not allowed to take anything other than personal items in their purses or wallets into the courtroom.

“At times, there may be white paper and pencils for the jurors to take notes,” he said.

On the official website of the city’s judiciary, there is information about the role of jurors but no mention of what one can or cannot do during a hearing, except that “during the course of the trial, you must not discuss any matters arising out of the trial with [others] except your fellow jurors and even then only within the privacy of the jury room”.

This was also stressed to the jury in Ho’s trial, with the judge reminding the panel at the end of each day: “Please remember, jurors, not to discuss the case with anyone, not to discuss the case among yourselves, not to research the case, and be on time.”

All 12 jurors in Ho’s case, as well as three substitutes who remained on standby throughout, were selected to listen to the complicated bribery and conspiracy case against the former Hong Kong home affairs minister, who faced eight charges under the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act.

In the American system, potential jurors must reveal personal background information under oath in a selection process held in open court. They have to disclose their jobs, describe their hobbies, say how many children they have, where their spouses work, what newspapers they read and what films they watch.

A prosecutor, a lawyer, a correctional facility employee, a police officer and an investigative reporter were among those not picked for the panel. All the selected jurors had a bachelor’s degree or higher qualification.

The group was ethnically diverse but did not include anyone of Chinese descent. Those selected said they had no strong negative or positive sentiments towards China. Most also said they were not frequent news consumers.

Each morning the jurors would troop in and be greeted by District Court judge Loretta Preska before they took their seats. As they passed Ho, he would smile warmly at them.

At the conclusion of the trial, the jurors had to discuss each charge against Ho and decide if he was guilty.

All jurors had to agree on every charge for the verdict to be complete. If only one juror had reason to doubt or disagree with the rest, the trial would fail and have to resume with a new jury.

This was not the case on Wednesday, and Ho was convicted on all charges except one involving money laundering in Chad. He will be sentenced on March 14.

Additional reporting by Ng Kang-chung