Hong Kong’s district council overhaul sparks soul-searching on future of direct elections even as pro-Beijing camp welcomes move towards stability at grass roots

- With only 88 elected councillors from 44 constituencies, ‘campaigning and representation will be affected’

- Sweeping changes in selection procedures signal return of pro-establishment councillors defeated in 2019

A shake-up loomed for the city’s 18 district councils, where an election held in 2019 saw pro-democracy opposition candidates sweeping in, only for most to resign or be disqualified within two years.

“We expected changes, but not to such an extreme,” said Democratic Party member Felix Chow Hiu-laam, a Sha Tin district councillor.

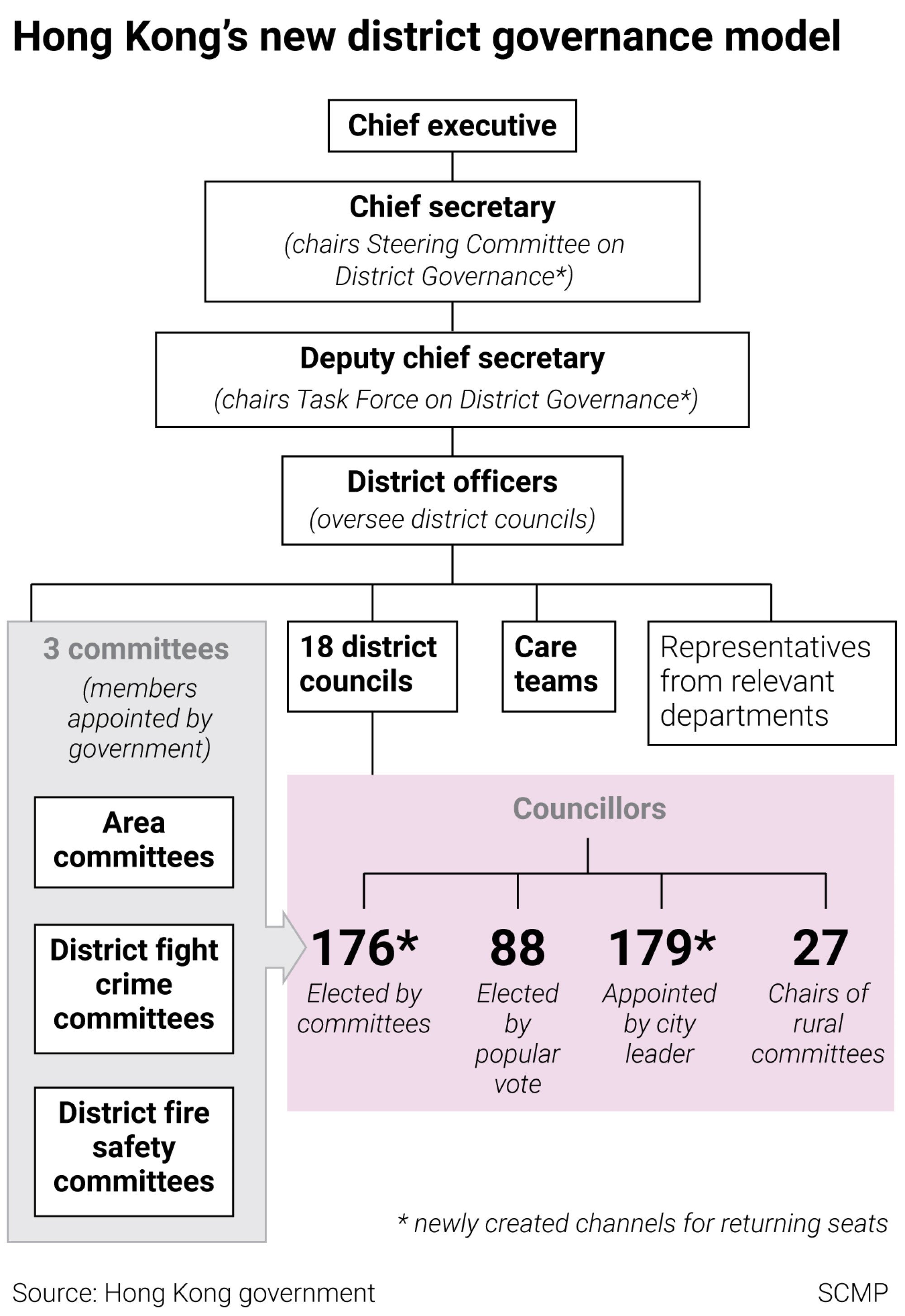

By the end of this year, the district councils will have a total of 470 representatives, with fewer than a fifth – 88 seats – decided by popular vote.

The bulk of the rest will be decided by the city leader, who will appoint 179, and three committees packed with pro-Beijing figures, who will choose 176, with 27 set aside for indigenous villagers.

Each district will have only two to eight directly elected seats. Candidates will have to secure nominations from the three committees and undergo national security vetting.

And, instead of having a councillor as chairman, district officers, the top officials at the district level, will preside over the councils.

Lee and his top officials were plain in saying the changes were meant to “depoliticise” the district councils, redirect them to focus on serving residents, and prevent “anti-China troublemakers” and those promoting separatism and violence from “manipulating and paralysing” the organisations as they did during the social unrest of 2019.

In elections that year, opposition candidates – many in their 20s and 30s – swept most of the 452 seats at stake.

Hong Kong lawmaker questions if district council revamp will just create ‘cheerleaders’

The overhaul transforms the district councils into “administrative-led” bodies that will be the least democratic since their formation four decades ago.

The move to empower district officials and government-endorsed pro-establishment figures was also more radical than many had expected.

To district councillor Chow, 27, the overhaul simply “allows the government to control everything”.

“Opposition is getting harder and harder,” he said.

Lawmaker Paul Tse Wai-chun, 64, a Wan Chai councillor, likened the revamp to “a long-awaited reset of the clock after populism jeopardised our society since 2019”.

“But still, we have to do more to convince residents how this overhaul can allow their voices to be better heard,” he said.

‘Campaigning will be costlier’

That year, one in three registered voters aged above 21 turned out to choose 132 directly elected representatives, who filled slightly over a quarter of all seats.

Gradual democratisation took place until 1994 when appointed seats were abolished and all district councillors were elected.

The appointment system returned after Britain returned the city to China in 1997, but from 2016, all district councillors were chosen by direct elections, except for 27 seats set aside for indigenous villagers.

This year, with most councillors to be appointed by the city leader or picked by three committees, the number of constituencies will be slashed from 452 to only 44, each electing two councillors.

This means that in future, each elected councillor will cover a much larger area and many more residents.

For example, Sha Tin, the city’s most populous district with 684,300 residents last year, will see the number of constituencies shrink from 42 to four.

That means each councillor will represent more than 10 times more residents, about 171,000 instead of 16,000 now.

Electing Hong Kong district councillors ‘could overlook candidates hesitant to run’

Sha Tin district council chairman Chris Mak Yun-pui, 36, said he wondered about the impact that would have on elections in these much-enlarged constituencies and the cost of campaigning.

“Assume we deliver just one flier to every elector, at the cost of HK$1 [12 US cents] each,” he said. “How many people can afford HK$200,000 [to produce only one campaign item], unless they are affiliated with resource-rich groups?”

Previously with the Democratic Party, Mak was among a minority of pro-democracy councillors who did not resign and were not disqualified after the national security law arrived.

A social worker and representative for Lee On Estate in Ma On Shan for 12 years, he was concerned about how the huge new constituencies would affect close ties between councillors and residents.

“I got to know the old people who live alone and drop by my tiny office regularly, and I notice when they stop showing up,” he said.

“Then, when I conduct home visits, I find that they need help or something has gone wrong. I am not sure how this kind of bonding can be sustained.”

Rise of the defeated candidates

Former district councillor Jackson Wong Chun-ping, 58, has no such worries. Previously with Beijing’s liaison office in the city, he is convinced the big changes coming up will result in residents being served better.

Established and new community groups packed with pro-Beijing figures would make a difference in the overhauled district council scene, he said.

Wong said Xia acknowledged and praised the sacrifices of those who continued serving the community despite being defeated in the 2019 district election, and agreed residents’ needs would be better served through more platforms.

Wong is one of 99 former councillors appointed to area committees after being defeated at the polls.

Hong Kong not legally required to set up district councils, justice minister says

As a district leader of the Kowloon Federation of Associations Kwun Tong District Committee, which has 47 member associations, he has been helping affiliated bodies bid for contracts related to new community care teams set up by the government.

“We have established a network with 3,200 volunteers and it keeps expanding. They can be mobilised to bridge service gaps on a daily basis or during emergencies,” he said.

A Post review of official documents showed that numerous pro-establishment district-level organisations have won government tenders to organise community visits and events promoting the national security law.

Everyone who hopes to stand for election under the overhauled rules will have to seek nominations from at least nine of more than 2,000 government-appointed members of area committees, district fire safety committees and district fight crime committees.

These groups are now empowered to nominate 176 representatives to run for district council seats.

District council appointees must commit to roles, Hong Kong’s No 2 official says

‘The cost of political correctness’

Throughout the past week, senior district officials have found themselves being described as “little chief executives”.

The overhaul will bring back a 1982 practice by putting them in charge of district councils, instead of having councillors elected as chairs. They will have the power to assign work to councillors and decide the agenda of meetings.

A new monitoring system will track councillors’ behaviour and allow the home affairs chief to initiate investigations if they fall below “public expectations”.

When city leader John Lee said he did not want to see councillors “manipulating and paralysing” the district councils, he was referring to what happened after the opposition swept the 2019 polls.

As it happened: pro-Beijing camp licks wounds after defeat in Hong Kong elections

Sha Tin councillor Johnny Chung Lai-him, 28, an independent from the pro-democracy bloc, was worried that a new overemphasis on “political correctness” might stifle voices challenging unpopular policies.

He recalled co-leading a campaign with residents’ concern groups to protest against development plans near Ma On Shan Country Park in 2020. He said the authorities suspended the project after he and other councillors presented 6,000 petitions in the Sha Tin District Council.

He asked: “Will similar acts breach new rules in future councils if one’s stance is not in line with government policy directions?”

Pro-democracy parties ponder next moves

The democratisation of Hong Kong’s municipal councils since the 1980s coincided with the rise of political parties.

The Association for Democracy and People’s Livelihood (ADPL) was founded in 1986, and the Democratic Party in 1994.

With the increase in the number of directly elected seats, they got together like-minded people to discuss Hong Kong’s post-handover future and stay competitive in district elections.

The rise of the pan-democrats prompted pro-Beijing forces to reorganise themselves, paving the way for the formation of the Democratic Alliance for the Betterment and Progress of Hong Kong (DAB) in 1992. It is now the city’s largest party.

For Hong Kong’s opposition camp, the question now is whether they should try for seats in the revamped councils.

Several founding leaders of the Democratic Party, including Emily Lau Wai-hing and Yeung Sum, have urged their colleagues not to give up, but others have their reservations.

At a recent closed-door meeting of core party members, many expressed concerns that the new rule requiring election candidates to obtain nominations from potential rivals would pose a major challenge.

No consensus was reached, but the party would submit its views on the reforms to the government during the two-week consultation period, chairman Lo Kin-hei said.

But Ramon Yuen Hoi-man, 36, the party’s Sham Shui Po district councillor, has decided not to run for a new term, to spend more time with his family.

He said the revamped district councils would no longer play the role of monitoring the government, and the opposition needed new channels to stay relevant.

“Opposition members should think of other ways, like teaming with NGOs, to speak for Hongkongers,” he said.

The party has no seats in the reformed legislature and only seven district council seats left, down from 89 in 2019.

Li Ting-fung, 41, ADPL’s Sham Shui Po district councillor, said his party members were “very dispirited” over the revamp. It won 19 seats in 2019, but only six councillors were still serving.

Li said the party would decide its position on the next district council election no earlier than next month.

Hong Kong’s district councils to be chaired by government officials

‘Top-down control at all levels’

He said Hong Kong was moving “from more to less political participation and less political accountability” as the authorities strengthened top-down control at all levels of administration.

He said authorities might hope that some opposition politicians would join the coming district election for diversity and increased legitimacy.

“Whether they will join, we’ll have to see. The space for pan-dems, who advocate more autonomous participation, accountability and transparency is shrinking every day,” he said.

Political scientist Ma Ngok, of Chinese University, said the overhaul marked not only the end of district councils as they had been for decades, but also the end of electoral politics in Hong Kong.

‘Only 20 per cent of Hong Kong district council seats’ to be directly elected

“People chosen in elections tend to excel in communicating with residents and gauging the public pulse, whereas those appointed by the authorities might tend to have a good working relationship with the government,” he said.

Veteran political commentator Sonny Lo Shiu-hing said that from a Western perspective, the district council overhaul was a “backsliding in democratisation”.

“But we could abandon using the Western yardstick to measure democratisation in Hong Kong,” he said. “The essence of Hong Kong-style democracy lies in governmental responsiveness.”

Having larger constituencies and fewer directly elected seats would not necessarily result in poor public service delivery and limited accountability of officials, he added.

“This will depend on whether the appointed and indirectly elected councillors have their offices open to the public. If they run offices just like the directly elected ones do, public service delivery should not be a problem,” he said.

Additional reporting by Jeffie Lam and Lilian Cheng