Hong Kong’s extradition protests: one country, two systems and a vicious circle of mistrust with Beijing

- Beijing is growing impatient with Hong Kong’s seeming inability to enact the national security law required under its Basic Law

- And this summer’s mass protests have again revealed a deep schism of distrust between both sides, fuelled by misunderstanding and paranoia

This sentiment has been echoed across the island and shared by some American politicians and overseas media outlets.

But what has transpired in Hong Kong has in fact shown that the formula has worked, albeit not in the way imagined by its creator, China’s late paramount leader Deng Xiaoping.

Scoffing in Singapore, praise in Philippines: Asia’s take on Hong Kong protests

The people of Hong Kong have spoken and through their bravery and coverage, they have saved the “two systems”.

But 22 years after Hong Kong was returned to Chinese rule, this summer’s mass demonstrations have again revealed a schism of deep distrust between Hong Kong people and the mandarins in Beijing, fuelled by misunderstanding and paranoia.

Deng’s one country, two systems was once hailed as a great political experiment which ensured the smooth and peaceful transfer of Hong Kong from British to Chinese rule in 1997. Under the principle, Hong Kong was guaranteed a high degree of autonomy and the city’s way of life and capitalist system would remain unchanged for 50 years.

In the early years following the return, the formula served Hong Kong quite well as both the people in Hong Kong and officials in Beijing wanted to show the rest of the world that the unique political experiment had worked. At that time, the emphasis from both sides was on the “two systems”, with Beijing hoping that its success would provide a model for eventual reunification with Taiwan.

Indeed, previous Chinese leaders were fond of using the proverb “river water should not interfere with well water” to signal a hands-off approach and that neither side should meddle with the other’s system.

The view from Singapore: Hong Kong is a city tearing itself apart

Since then, a vicious cycle has taken hold, in which each side thinks the worst of the other, on every major political development or incident.

In Hong Kong, residents are worried about Beijing’s attempts to tighten its grip on the city, while the officials in Beijing are concerned about losing control of the city.

In 2012, the Hong Kong government under Leung Chun-ying was forced to shelve the plan to introduce national education teaching in local schools after mass protests.

It’s not just Hong Kong, Asia has a rich history of protests: here are 5

Indeed, ever since 2003, successive chief executives have said the local government would not shirk its duty under Article 23, but would need to find a suitable time to introduce the law – although they all failed to give any time frame.

Since 2014, Chinese officials have started to suggest that “one country” should take priority over “two systems” and some mainland advisers have warned that Beijing could step in and take action if the delay continues. No doubt, such talk has in turn heightened the worries of the people of Hong Kong.

While those economic factors play an important part, the latest demonstrations have clearly shown that distrust of Beijing is the biggest cause.

Like her predecessors, Lam is also under pressure to enact the national security law but has remained non-committal about the time frame.

But Lam apparently saw the introduction of the extradition bill as a path to secure Beijing’s support for her re-election for a second term in 2022. As written in this space last week, she also believed the law could help plug a legal loophole and bring justice for the aggrieved family of the girl brutally murdered by her ex-boyfriend in Taiwan.

There is credible speculation in Beijing that when Lam first notified the central government about her intention to introduce the bill, initial reactions were lukewarm, not least because officials were more concerned with the enactment of the national security law.

Will Beijing still support Carrie Lam after extradition bill debacle?

It remains unclear why Beijing later changed its mind and decided to back Lam on the legislation, as central government officials should have been more politically sophisticated in weighing the geopolitical risks associated with the introduction of the law.

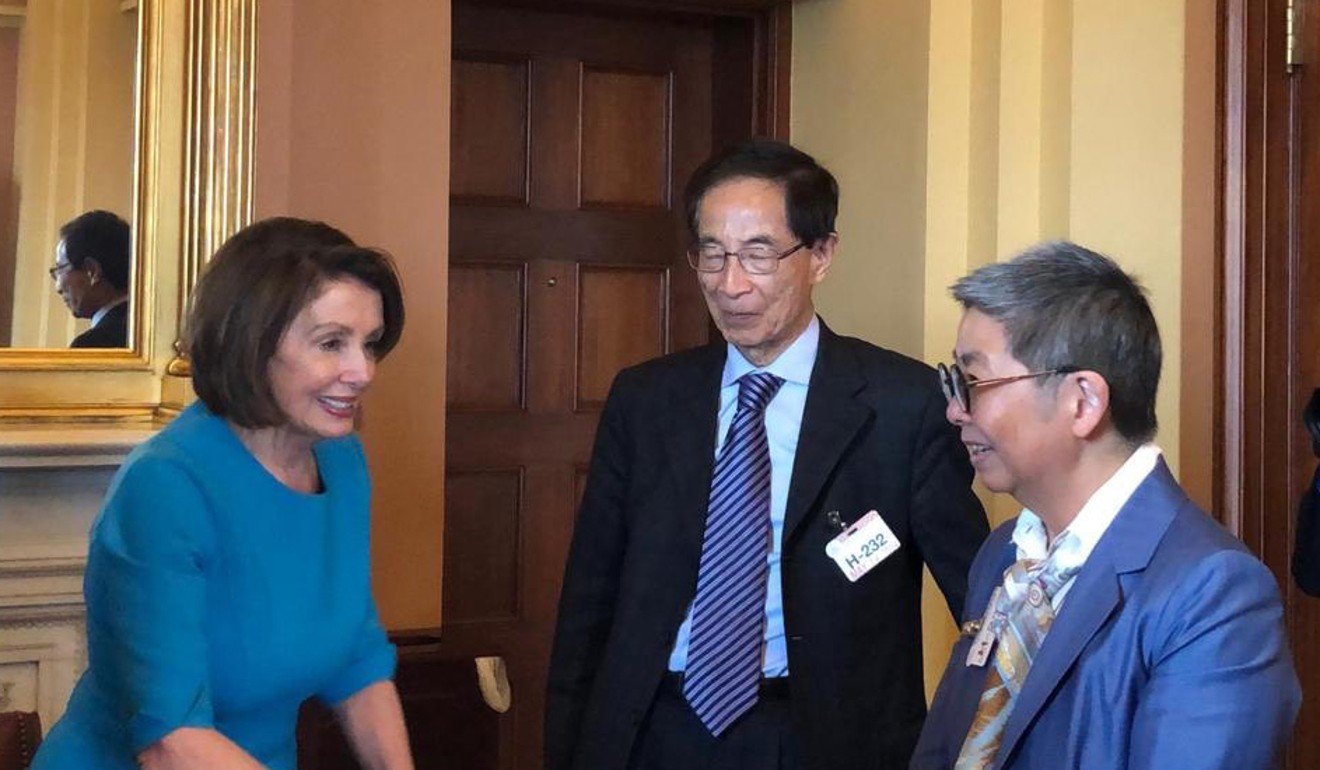

One suggestion was that Beijing started to harden its support for Lam after the British and Canadian foreign ministers expressed concerns about the proposed bill in a joint statement, along with the 28-member European Union, and after Martin Lee Chu-ming and a small team of other pro-democracy activists from Hong Kong visited Washington to seek the United States’ support to oppose the law.

Such fears will further compel Beijing to be more assertive over Hong Kong affairs despite the climbdown from the proposed extradition bill. But any such moves are bound to meet stiff resistance from the people of Hong Kong.

The formula of “one country, two systems” is still holding on in Hong Kong but its path is narrowing because of the deepening distrust on both sides. ■

Wang Xiangwei is the former editor-in-chief of the South China Morning Post. He is now based in Beijing as editorial adviser to the paper